By Clara Marcelli and Anne-Maëlle Evo.

Introduction

Rwanda will hold its next presidential and parliamentary elections in a few months. Paul Kagame – President since 2000, although effectively in control since 1994 – stands for re-election [1]. While he is eligible to do so [2], former EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini, warned that the constitutional amendment that allowed him in 2015 to stay in office for another seventeen years undermined democratic principles [3].

However, Paul Kagame, unmoved by Western criticism, is proud of the trust Rwandans place in him, [4] and still derives immense legitimacy from his reputation as guarantor of post-genocide stability [5]. Twenty years ago, whilst leader of the Rwandan Patriot Front, he had defeated Hutu extremist forces to end a genocide that had claimed some 800,000 victims between April and July 1994 [6]. Six years later, he was officially elected as the head of a rural country in pieces, with a traumatised population and an economy in tatters. Embracing these immeasurable challenges, Paul Kagame has since strived to instill in Rwandans a sense of national unity and made Rwanda one of the most dynamic economies on the continent [7]. From 2009 to 2019, the tiny East African nation sustained a 5% per capita GDP growth yearly. Even the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, the climate-related shocks, and the mounting inflationary pressures did not halt the country’s growth, which recorded a substantial 8.2% real GDP increase in 2022 [8].

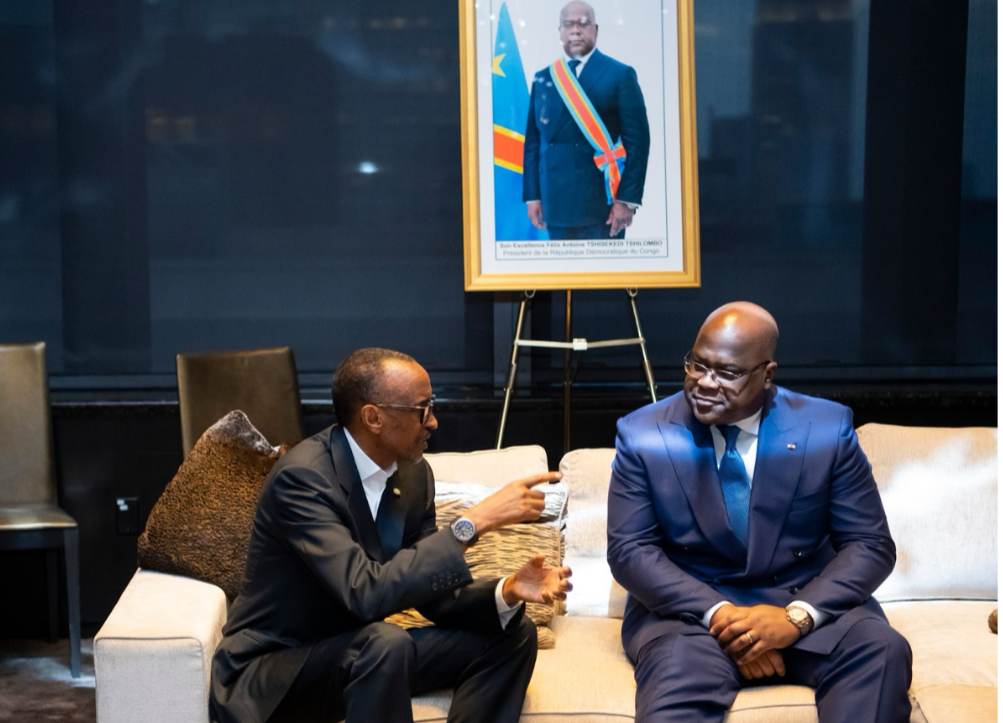

Rwanda is today described as “Africa’s most inspiring success story”, as well as one of the most stable countries on the continent [9]. However, the country has faced mounting criticism for what human rights groups describe as the quelling of political opposition and the muzzling of independent media voices [10]. Moreover, the recent statement from Félix Tshisekedi, the President of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), showed his intention to declare war on its neighbour : “If you re-elect me and Rwanda persists […] we will march on Kigali”. He has since been reelected [11].

While the DRC claims to have so far lost the media war against Rwanda [12], the escalating tensions between the two countries are increasingly shedding light on the darker side of Rwanda’s recent development success story.

Shadows of the past: the shifting dynamics of Rwanda – DRC relations

Two enemy pawns on the Cold War chessboard

Modern relations between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda have origins that date back to the colonial era. Both Belgian colonies between 1919 and 1960, they experienced violent upheavals during their first years of independence.

The DRC was left with a weak central authority and quickly became a pawn on the chessboard of the Cold War. Fearing that the country’s strategic mineral resources would join the Soviet sphere of influence, Western Europe and the United States provided military, economic, and diplomatic support to the Presidency of Mobutu Sese Seko [13]. However, the end of the Cold War marked a turning point. Mobutu, who had subjected Congo to thirty years of kleptocratic and dictatorial government [14], lost much of the Western financial support that had been provided in return for his role as a bulwark against communism in Africa, and guarantor of western economic interests in the mining sector [15]. Mobutu was left powerless in 1994–when the President of neighbouring Rwanda was assassinated–and the genocide unraveled in the space of 100 days.

The build-up of the Rwandan genocide

Although the responsibility for the genocide primarily rests with the individuals who orchestrated and carried out the mass killings, this complex and multifaceted tragedy cannot be fully understood without considering the indelible mark left by the Belgian colonial rule on Rwanda. For 30 years, the Belgians favoured the Tutsi minority over the Hutu majority and institutionalised ethnic differences, going so far as to introduce identity cards labelling each individual as either Tutsi, Hutu, Twa or Naturalised [16]. This exacerbated existing societal divisions, leading to a sense of ostracization among the majority of Rwandans. The ID card system, which was maintained after independence, sowed the seeds of resentment and once computerised, became the perfect genocidal tool [17].

When Belgium relinquished power in 1962, the Hutus took their place, and over the subsequent decades, portrayed the Tutsis as the scapegoats for every crisis. Many of them sought refuge in Uganda; Paul Kagame was one of them. Once there, he joined the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) to overthrow Rwandan President Habyarimana and secure the Tutsis’ right in their homeland [18]. In April 1994, Habyarimana’s plane was shot down, killing both him and Burundi’s President, also Hutu. While it remains unclear who was responsible, the Rwandan government felt attacked and responded with increasingly extremist rhetoric, mobilising Hutu against Tutsi in an organised and coordinated media campaign [19]. A few hours after the President’s death, extremist Hutu militia had already begun systematically murdering Tutsis and moderate Hutus, with a brutality that shocked the world [20]. Within three months in 1994, an estimated 800,000 people were killed, many others were physically and psychologically afflicted for life through rape, maiming, and other war crimes [21]. Moreover, over two million fled to neighbouring countries as the international community stood by [22].

The DRC, pulled into the dance before being subordinated

The DRC had remained relatively aloof from internal tensions in Rwanda, as most Tutsi had sought refuge in Ouganda [23]. However, when they successfully re-entered Rwanda and halted the genocide, came along the desire for justice. The Hutus were thus now the ones feeling the need for a refuge. Millions of them fled to Zaire, former DRC, settling in huge camps set up by the United Nations; this fundamentally destabilised the country to this day. Paul Kagame, now at the head of Rwanda, claimed a right to pursue them across borders to eradicate the genocidal forces, who, sheltered by the international community in Goma, could use their base to continue wrecking death on Rwandan territory [24].

The RPF army crossed the border into Zaire in 1996, which marked the start of the first Congo war.

Observing the vulnerability of the DRC’s defence capacities, Paul Kagame not only pursued the Hutus but also supported rebel armed forces, largely composed of Rwandan and Congolese Tutsis, to help oust Mobutu in 1997. After a brutal and tumultuous conflict, they replaced him with Laurent-Désiré Kabila, a Rwandan ally in the war against genocidaires and political opponents [25].

However, this new DRC president soon decided to get rid of Rwanda’s perceived burdensome influence, accusing them of intending to create an empire: Tutsi land. On July 27, 1998, he announced the expulsion of all foreign officials, mostly Tutsis, from DRC and dissolved the non-Congolese units of the army [26]. In retaliation, Rwanda and Uganda, supported by the United States, orchestrated the uprising of the Tutsis in Congo and the capture of the city of Goma. Lacking the military capabilities to impose its will, Kabila formed a vast military coalition, including countries and armed militias. The Second Congo War, also known as the ‘Africa’s World War’ was a frenzy of violence involving at least 9 African countries and several dozen armed groups, all tied in an intricate web of ethnic conflicts, power struggles and economic incentives [27].

Profound disparities exacerbating to this day the existing tensions

Social and economic development

Despite the end of the Congo Wars in 2003, the long history of conflict and instability has sustained an ongoing humanitarian crisis. The first peaceful transition of power was in 2019, with the accession to power of Félix Antoine Tshisekedi Tshilombo. However, the DRC is still among the five poorest nations in the world, with nearly 62% of Congolese living on less than $2.15 a day in 2022 [28].

Rwanda, on the other hand, has come a long way. Its GDP has grown at one of the highest rates in the world between 2000 and 2020, ranking second in Africa [29]. The country now has modern, effective governance mechanisms and supports technological innovation to become the “Singapore of Africa” [30]. Despite one-third of the population still living from subsistence farming, poverty and gender inequality have declined and Rwanda is one of only two African countries to have achieved the Millennium Development Goals for health [31].

Demographic and territorial disparities

Nevertheless, Rwanda’s geography and population density hamper its long-term development [32]. The small, landlocked country has the highest population density in Africa. Its overpopulation pressure, coupled with the declining fertility of its soil, exacerbates societal tensions. Balancing the need for pastures for the growing number of Tutsi-owned cattle with the need for farmland for an increasing number of Hutu peasants could sometimes worsen already tense relationships [33]. Now let’s consider neighbouring DRC, sub-Saharan Africa’s most extensive and less densely populated country [34]. Today, Rwanda is sometimes said to consider Eastern Congo an extension of its own territory [35]. Its population gradually spreads across the borders, with the apparition of an increasing number of Congolese Tutsi, and a Rwandan regime now even claims to be in charge of the protection of all Tutsis, including those living in the DRC [36].

Resource disparities

The Democratic Republic of Congo is not only the largest country in Sub-Saharan Africa, but it is also considered the world’s richest country in terms of wealth in natural resources [37]. In recent years, these resources have been at the stake of many tensions, conflicts and shenanigans on the part of countries wishing to monopolise this wealth, over and above international law. According to several reports, Rwanda is no stranger to this [38].

Lately, the security situation in North Kivu and Ituri Congolese provinces has deteriorated dramatically, with fighting between the army and armed groups. The United Nations, United States, and other Western countries have accused Rwanda of actively supporting the 23 March Movement (M23), one of the armed groups threatening the security and stability of the eastern provinces of the DRC and the entire region [39]. Amongst other things, the M23 claims to defend the interests of the Congolese Tutsi and Kinyarwanda-speaking minorities. The group instigated a rebellion in North Kivu in 2022, an offensive put down by the Congolese army. Although they agreed on a ceasefire in 2023, UN reports warn that the conflict could flare up again at any moment [40]. The tensions between the countries are at an all-time high, especially since a leaked report from UN experts provided solid evidence of Rwanda’s army running military operations against DRC and providing “troop reinforcements, especially weapons, for specific M23 operations” [41]. Last month, Congolese President Tshisekedi compared Kagame’s expansionist aims to Hitler’s before threatening to invade Rwanda: «I’ve had enough of invasions and M23 rebels backed by Kigali, Kagame out! » [42].

Instability opens the door to easier relays of exploitation. In 2002, a panel of experts with a mandate from the Security Council had already denounced Rwanda’s exploitation of gold, diamonds, cassiterite, coltan, and timber in Eastern Congo. Within the mining areas, Congolese civilians were forced to sell the minerals to Rwandese officers at a preferential rate, and 60% to 70% of the coltan that left from Eastern Congo was exported from small airports to Kigali or Cyangugu [43]. Rwanda, which never had the resources to be a mineral exporting country, has today become one [44].

We must note that if these resources have long escaped the control of the state, it is not only on account of foreign interference, as the plundering of Congo was systematically organised with the help of the Congolese elites [45].

Human Rights violations

Allegations of violations

The extent of this conflict raises major human rights concerns in Eastern Congo. In 2012, UN investigators reported a high number of allegations of violations of human rights and international humanitarian law by M23 soldiers [46]. The armed group was deemed responsible for the killing of civilians, abductions as well as widespread sexual and gender-based violence. Last year, Human Rights Watch completed this analysis with a report on the abuses committed by M23 troops against civilians between November 2022 and March 2023.

Those reports shed light on indiscriminate executions, penal servitude, and rapes, in particular gang rapes. A survivor related how M23 rebels stole her money and shot her mother in the chest for trying to defend her family: “Then four of them raped me. While they were raping me, one of them said: We have come from Rwanda to destroy you” [47]. A former resident of Kanombe, who lived under M23 occupation after they seized the city in August 2022, reported the rebels’ words: “Anyone who is against us will die. We’re not here to fight; we’re here to take back our land”. Interviewed by Human Rights Watch, he described how they raped women, beat men, and forced people to give them their crops [48]. These harrowing testimonies only give us a glimpse into the daily lives of millions of civilians trying to survive this humanitarian crisis, notably affecting the poorest and women.

Another main source of concern is child recruitment by armed groups, which has dramatically increased over the past years. Several initiatives and laws attempt to address this issue. In the US, the Child Soldier Prevention Act of 2008 aims to criminalise military forces recruiting child soldiers and prohibit peacekeeping operations assisting countries using child soldiers [49]. However, it has been proven that groups such as M23 keep recruiting them under the false pretence of employment to bypass potential international sanctions [50]. In a country where rural areas have a 48% of school enrolment rate, the poor and uneducated are the first to be recruited. In addition, the 2022 M23 attack displaced 450 000 people, on top of the 6.1 million of Congolese [51] who have been internally displaced since the beginning of the year by armed groups.

It is worth noting that this highly turbulent region, marked by an intricate web of conflicts and actors, allegedly witnesses human rights violations committed by both Rwanda and the DRC-related groups. According to Human Rights Watch, the Congolese military has supported armed groups, such as the FDLR, the Democratic forces for the liberation of Rwanda, who were involved in severe cases of abuses. Moreover, the UN report mentions “at least 126” cases of rape by the National Army, which is expected to protect the population [52]. Now that both Rwanda and DRC’s respective support of M23 and FDLR has been attested, the issue inevitably gains momentum insofar as not only the armed groups are held responsible for those crimes but also the country that supports them.

International condemnation despite inefficacy of solutions

Since the latest UN report, many countries and non-governmental organisations have urged parties “to ensure strict respect for human rights and international humanitarian law” as OHCHR said [53].

Regretfully, it’s not the first time that the United Nations and the international community have condemned those actions. In 2008, the DRC Mapping Report intended to map the most serious human rights violations committed within the DRC in the wake of the genocide, armed aggression, and war that took place between 1993 and 2003 [54]. Despite those condemnations, it seems that the international community has struggled, not to say failed, to safeguard human rights in the region.

The United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO) has played a main role in the conflict. With 21,000 soldiers involved, the Kivu conflict constitutes the largest peacekeeping mission currently in operation. For decades, they have sought to prevent force escalations and minimise human rights abuses. However, last month, Congolese authorities called for the UN to withdraw its troops by the end of 2024. They deplored their failure to control the rebellion and protect civilians from armed groups, which, after 25 years of presence, kept plaguing the eastern DRC in areas such as North Kivu, South Kivu, and Ituri provinces [55].

At the same time, the government has ordered the withdrawal of the East African community forces for very similar reasons. The Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi and some local presidents even accused the forces of cohabiting with the rebels rather than forcing them to lay down arms [56] as illustrated by the anti-MONUSCO protests in July 2022. Today, DRC’s capacity to take full responsibility over its population’s security is a critical concern. Several members of the Security Council fear that their withdrawal will create security vacuums, which will even further weaken the protection of civilians [57].

Conclusion

Over the past three decades, the world has borne witness to the rebirth of Rwanda, a tour de force that garnered considerable media attention. However, amidst this narrative, an increasing number of reports suggest that the country’s development is occurring at the expense of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Rwanda’s desire to hunt down the genocidaires who had taken refuge in the DRC was allegedly intertwined with economic and territorial ambitions, which partly lie at the root of the violent crisis that the DRC has been suffering for several decades. The conflict, which had already claimed 5.4 million lives between 1998 and 2007 [58], is today responsible for the internal displacement of about 7 million people [59]. International efforts, notably from the United Nations, have yielded few results and appear compromised.

The longest-standing humanitarian crisis in Africa, which hardly anyone talks about anymore, will have to mobilize new levers to find lasting deconfliction. Since the notable governance deficiencies in DRC, coupled with the country’s inherent political and ethnic rivalries, exacerbate the situation, a potential way forward could lie in setting up a governance system geared towards fighting corruption and strengthening military Congolese capabilities. In this crisis, as in others on the African continent, the long-awaited favourable outcome can only come from an African solution backed by regional powers or continental bodies, with the support of the course of the international community.

Edited by Justine Peries.

References

[1] George Obulutsa, Rwanda’s veteran president Kagame to seek re-election in 2024, Reuters, 20 Sept. 2023

[2] Tracy McVeigh, Rwanda votes to give President Paul Kagame right to rule until 2034, The Guardian, 20 Dec. 2015

[3] Rwandan bid for Kagame third term undermines democracy, says Mogherini, Euractiv, 4 Dec 2015

[4] Au Rwanda, Paul Kagame candidat à un quatrième mandat en 2024, Le Monde Afrique, 20 Sept 2023 https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2023/09/20/au-rwanda-paul-kagame-candidat-a-un-quatrieme-mandat-en-2024_6190174_3212.html

[5] Bruno Meyerfeld, Paul Kagamé ou le risque de l’isolement, Le Monde, 27 août 2016 https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2016/08/27/paul-kagame-ou-le-risque-de-l-isolement_4988738_3232.html

[6] Au Rwanda, Paul Kagame candidat à un quatrième mandat en 2024, Le Monde Afrique, 20 Sept 2023 https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2023/09/20/au-rwanda-paul-kagame-candidat-a-un-quatrieme-mandat-en-2024_6190174_3212.html

[7] Fonds monétaire international (FMI). “Africa Regional Economic Outlook: Special Issue.” FMI, octobre 2023 https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/REO/AFR/2023/October/English/africa-special-issue.ashx.

[8] World Bank. “Rwanda Overview.” World Bank https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/rwanda/overview

[9] Gatete Nyiringabo Ruhumuliza, Kagame’s Rwanda is still Africa’s most inspiring success story, AlJazeera, 21 Oct. 2019

[10] Rwanda: Wave of Free Speech Prosecutions, Human Rights Watch, 16 March 2022

https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/03/16/rwanda-wave-free-speech-prosecutions

[11] Shola Lawal, Could DR Congo’s Tshisekedi declare war on Rwanda if re-elected?, AlJazeera, 21 Dec. 2023

[12] Karine Rongba, Margaux Queffelec, “Pourquoi les médias ne parlent pas de la guerre au Congo (RDC).” Radio France, 16 Nov. 2023

https://www.radiofrance.fr/mouv/pourquoi-les-medias-ne-parlent-pas-de-la-guerre-au-congo-rdc-9938887

[13] Giovanni Carbone, Aa.vv., Paolo Magri, Leaders for a New Africa: Democrats, Autocrats, and Development, “Rebuilding the Congo after the kabilas” 2019 https://repository.uantwerpen.be/docman/irua/683be6/163429.pdf

[14] Felipe Antonio Honorato, Guilherme Silva Pires de Freitas, A brief history of Joseph Mobutu’s kpletocracy, LSE, 8 June 2023 https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2023/06/08/a-brief-historical-review-of-joseph-mobutus-kleptocracy/

[15] Giovanni Carbone, Aa.vv., Paolo Magri, Leaders for a New Africa: Democrats, Autocrats, and Development, “Rebuilding the Congo after the kabilas” 2019 https://repository.uantwerpen.be/docman/irua/683be6/163429.pdf

[16] United Nations. “Historical Background of the Genocide in Rwanda.” United Nations

https://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/historical-background.shtml

[17] United Nations. “Exhibits from the Panel of Experts – Set 3.” United Nations

[18] Amy McKenna, Rwandan Patriotic Front, Britannica, 28 April 2023 https://www.britannica.com/topic/Rwandan-Patriotic-Front

[19] Matthew Lower and Thomas Hauschildt, The Media as a Tool of War: Propaganda in the Rwandan Genocide, Human Security Center, 9 May 2014 http://www.hscentre.org/sub-saharan-africa/media-tool-war-propaganda-rwandan-genocide/

[20] Jason Burke, France ‘did nothing to stop’ Rwanda genocide, report claims, The Guardian, 19 April 2021 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/19/france-did-nothing-to-stop-rwandan-genocide-report-claims

[21] Department of Public Information, Sexual Violence: a Tool of War, March 2014 https://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/assets/pdf/Backgrounder%20Sexual%20Violence%202014.pdf

[22] Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques (OCDE). “United States – Evaluation of Development Cooperation.” https://www.oecd.org/derec/unitedstates/50189653.pdf

[23] The New Humanitarian, “Rwanda-Uganda: La première vague de réfugiés retourne au pays.” ReliefWeb, 20 Jan 2004

[24] Yann Gwet, Dans le conflit Rwanda-RDC, l’histoire bégaie-t-elle ?, Jeune Afrique, 8 Jan. 2023

https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1400635/politique/dans-le-conflit-rwanda-rdc-lhistoire-begaie-t-elle/

[25] JOSEPH BARAKA, Deuxième guerre du Congo: causes, acteurs, déroulement et conséquences, La Republica, 24 April 2023 https://larepublica.cd/kongopaedia/22042/

[26] Stephen Smith, Comment Kabila s’est fait chasseur de tutsis. Le tombeur de Mobutu prêt à tout pour sauver son pouvoir., Libération, 28 août 1998 https://www.liberation.fr/planete/1998/08/28/comment-kabila-s-est-fait-chasseur-de-tutsis-le-tombeur-de-mobutu-pret-a-tout-pour-sauver-son-pouvoi_244539/

[27] JOSEPH BARAKA, Deuxième guerre du Congo: causes, acteurs, déroulement et conséquences, La Republica, 24 April 2023 https://larepublica.cd/kongopaedia/22042/

[28] World Bank. “Democratic Republic of the Congo – Overview.” World Bank

https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/drc/overview

[29] Jules Porte, Rwanda: an effective development model, rising to the challenge of its sustainability, AFD, March 2021 https://www.afd.fr/en/ressources/rwanda-development-model-sustainability

[30] Masimba Tafirenyika, Rwanda : l’économie dopée par les nouvelles technologies, UN, April 2011

[31] World Bank. “Rwanda Overview.” World Bank https://www.banquemondiale.org/fr/country/rwanda/overview

[32] Jules Porte, Rwanda: an effective development model, rising to the challenge of its sustainability, AFD, March 2021 https://www.afd.fr/en/ressources/rwanda-development-model-sustainability

[33] Institute for Security Studies. “Land and Conflict: Lessons from The Rest of Africa.” Institute for Security Studies

[34] World Bank. “Democratic Republic of the Congo – Overview.” World Bank https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/congo/overview

[35] Teresa Nogueira Pinto, Is the Third Congo War approaching?, GIS, 12 April 2023

[36] Teresa Nogueira Pinto, Is the Third Congo War approaching?, GIS, 12 April 2023

[37] World Bank. “Democratic Republic of the Congo – Overview.” World Bank https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/congo/overview

[38] Tom Wilson and Andres Schipani, DRC says Rwandan mineral smuggling costs it almost $1bn a year, Financial Times, 21 March 2023 https://www.ft.com/content/ecf89818-949b-4de7-9e8a-89f119c23a69

[39] Rwanda backing M23 rebels in DRC: UN experts, AlJazeera, 4 Aug 2022 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/8/4/rwanda-backing-m23-rebels-in-drc-un-experts

[40] UN internal report flags rebels flouting ceasefire in eastern DRC, AlJazeera, 6 Jan 2023

[41] Morgane Le Cam, Confidential UN report provides ‘solid evidence’ of Rwanda’s involvement in the East DRC, Le Monde, 5 May 2022

[42] Shola Lawal, Could DR Congo’s Tshisekedi declare war on Rwanda if re-elected?, AlJazeera, 21 Dec. 2023

[43] “Security Council Imposes Sanctions on Taliban.” United Nations, 20 Dec. 2001

https://press.un.org/en/2001/sc7057.doc.htm

[44] Judi Rever, Rwanda is the ‘Wild West’ and should be removed from the mineral supply chain, 25 Sept 2023 https://canadiandimension.com/articles/view/rwanda-is-the-wild-west-and-should-be-removed-from-the-mineral-supply-chain

[45] Panel of Experts. “Plundering of DR Congo Natural Resources: Final Report.” ReliefWeb, 2002

[46] International Committee of the Red Cross. “Democratic Republic of the Congo: Involvement of MONUSCO.” Casebook of the International Committee of the Red Cross, 2012

https://casebook.icrc.org/case-study/democratic-republic-congo-involvement-monusco

[47] Human Rights Watch, RD Congo : Meurtres et viols commis par les rebelles du M23, soutenus par le Rwanda, 13 Juin 2023

[48] Human Rights Watch, RD Congo : Meurtres et viols commis par les rebelles du M23, soutenus par le Rwanda, 13 Juin 2023

[49] Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2011.” Congrès, 112e Congrès, H.R. 2519, 2011

https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/2519

[50] Perry M, Sanctions against M23 for recruiting child soldiers under the false pretense of employment, Change.org, 16 April 2023

[51] Nearly 1 Million Newly Displaced in DRC in First Half of 2023 Amid Surge in Violence, IOM UN Migrations, 15 June 2023

https://www.iom.int/news/nearly-1-million-newly-displaced-drc-first-half-2023-amid-surge-violence

[52] International Committee of the Red Cross. “Democratic Republic of the Congo: Involvement of MONUSCO.” Casebook of the International Committee of the Red Cross, 2012

https://casebook.icrc.org/case-study/democratic-republic-congo-involvement-monusco

[53] Documented cases of human rights abuse emerge against M23 armed group in DR Congo, UN News, 21 Dec. 2012

https://news.un.org/en/story/2012/12/428982

[54] UN Releases DR Congo Report Listing 10 Years of Atrocities, Identifying Perpetrators.” ReliefWeb, 2010

[55] All UN peacekeepers to leave DR Congo by end of 2024, AlJazeera, 13 Jan 2024

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/1/13/un-says-all-peacekeepers-will-leave-dr-congo-by-end-of-2024

[56] East African regional force starts withdrawing from DRC, France 24, 3 Dec 2023

[57] Mission Drawdown in Democratic Republic of Congo Must Not Create Stability Vacuum, Jeopardize Civilian Protection, Senior Official Tells Security Council, UN News, 26 June 2023

https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15334.doc.htm

[58] International Rescue Committee. “IRC Study Shows Congo’s Neglected Crisis Leaves 5.4 Million Dead.” ReliefWeb, 2008 https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/irc-study-shows-congos-neglected-crisis-leaves-54-million-dead

[59] RDC : près de 7 millions déplacés par les violences, la grande majorité a besoin d’aide, UN News, 30 Oct 2023 https://news.un.org/fr/story/2023/10/1140132

[Cover Image] Photo of President Kagame with President Félix Tshisekedi of the Democratic Republic of Congo, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed

Leave a comment