By Lorenzo Cappelletti.

In recent months, tensions in the South China Sea have escalated dramatically, particularly surrounding the contentious Spratly Islands. Events like the reported use of lasers by Chinese vessels to blind Filipino ship crews and a collision between a Chinese vessel and a Philippine supply ship near the Second Thomas Shoal underscore the ongoing volatility of this geopolitically sensitive area, which has long been a focal point of international attention [1][2].

As China grows increasingly assertive, other regional players, such as Vietnam and the Philippines, are countering Beijing’s ambitions with strategic support from the U.S. and Japan [8][10][11]. In this analysis, we’ll delve into the dynamics mentioned to understand what’s driving these tensions and their broader implications.

Historical Background

Home to vital archipelagos such as the Paracel and Spratly Islands, the South China Sea has a complex history shaped by colonial legacies, treaties, and the evolving ambitions of regional powers. This section will review historical developments from the past century to provide relevant context for this investigation.

After the Spanish-American War, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States through the 1898 Treaty of Paris. Scarborough Shoal and the Spratly Islands remained under Spanish sovereignty. Following negotiations in 1900, the Treaty of Washington adjusted the terms retroactively and transferred these territories to the United States [3]. The nearby Paracel Islands, instead, were claimed and occupied by France in 1932 [3]. By 1939, much of Southeast Asia, including the Paracel and Spratly Islands, fell under Japan’s control. During WWII, these islands became an important base for several military operations [4].

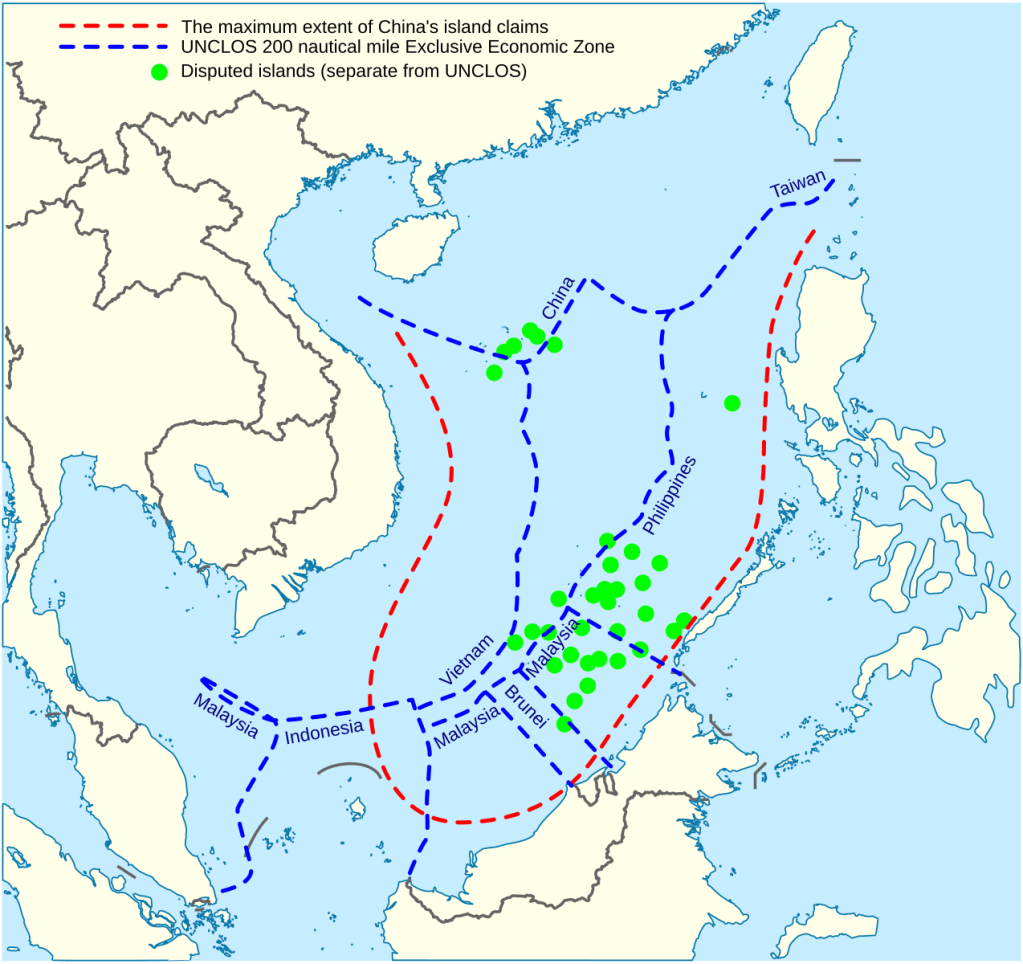

After Japan’s defeat in World War II, China asserted its claim over the whole South China Sea with the “eleven-dash line,” a demarcation line extending near the coasts of several Southeast Asian nations, by the Republic of China (ROC) in 1947 [4]. This line comprehended both the Spratlys and Paracels, justifying its ambitions over the islands based on historical records. In 1949, however, The Chinese Civil War led to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which adopted a modified “nine-dash line” (which excluded Vietnam’s territory to improve relations with North Vietnam [3] [4].

Both the ROC (current government of Taiwan) and PRC maintained claims over the region, joined by other Southeast Asian nations, such as Vietnam –which claimed the islands at the San Francisco Peace Conference in 1951. The discovery of petroleum resources in the 1970s increased interest in the South China Sea, and several claimants, including South Vietnam, the Philippines, and Taiwan, occupied different islands [5].

The emerging and complex dynamics resulted in several clashes. In 1974, as North Vietnam neared victory in the Vietnam War, the People’s Republic of Chi seized Yagong Island and reefs in the Paracels from South Vietnam, concerned that they could fall under North Vietnamese and Soviet influence. Another confrontation occurred in 1988 near Johnson Reef, where PRC forces clashed with Vietnam to secure Fiery Cross Reef [5].

The establishment of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in the early 1980s further complicated matters by introducing the concept of exclusive economic zones (EEZs), making control over the South China Sea even more appealing [5]. By the late 20th century, a network of competing claims had formed over the Spratly Islands, with Vietnam, China, Taiwan, Malaysia, and the Philippines each maintaining garrisons to reinforce their positions [5]. Since the 1990s, however, control over these territories has largely stabilized. China currently controls all islands in the Paracels, while in the Spratlys, Vietnam occupies 29 islands, followed by the Philippines with eight, Malaysia with five, China with five, and Taiwan with one [3].

Recent Developments

On July 20, 2011, China, Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam agreed on preliminary guidelines for implementing the 2002 Declaration of Conduct (DOC) of Parties in the South China Sea, aimed at enhancing cooperative solutions to their overlapping claims. However, tensions quickly resurfaced with periodic escalations driven by China’s intimidation tactics [3].

- In early 2012, China and the Philippines faced a prolonged maritime standoff over the Scarborough Shoal, with both accusing each other of encroachments. Later that year, unverified reports alleged that the Chinese navy had sabotaged two Vietnamese oil exploration operations, sparking anti-China protests in Vietnam. The following year, the Philippines took a further step by bringing a case under the UN Convention on the Laws of the Sea (UNCLOS) [6].

- In 2014, China deployed an oil rig near the Paracel Islands. Vietnam dispatched naval vessels in an attempt to stop China from establishing an oil rig in contested waters near the Paracel Islands. The encounter quickly escalated as China sent forty ships to protect the rig, and several vessels collided [7].

- In 2016, Beijing installed surface-to-air missiles on Woody Island, a land mass in the Paracel Island. U.S. and regional officials warn that the deployment may signal a “militarization” of the maritime disputes, while China argues that the installation of missiles falls within its rights for defense on what it considers sovereign territory [7].

- In 2018, a U.S. destroyer narrowly avoided colliding with a Chinese destroyer near the Spratly Islands. The Pentagon says the Chinese ship, the Lanzhou, passed within forty-five yards of the USS Decatur, which was conducting a routine freedom of navigation operation [7].

- In 2019, Manila also accused a Chinese trawler of ramming a Filipino fishing boat, resulting in the rescue of its crew by Vietnamese fishermen [6].

- In March 2021, China deployed two hundred ships to Whitsun Reef, part of the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ). While Beijing claims that the ships are a “fishing fleet,” Manila says they appear to be operated by military personnel. Again, in early 2023, the Philippines reported that Chinese vessels had been using lasers to temporarily blind Filipino ship crews, blocking Philippine vessels, and conducting aggressive maneuvers [1].

- Under the administration of Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., who took office in 2022, tensions escalated over the Second Thomas Shoal in the Spratly Islands, located within the Philippines’ 200-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ). In June 2024, a Chinese vessel and a Philippine supply ship collided in the area, with both countries blaming each other for the incident [2].

Strategic and Economic Importance

As the previous paragraphs may have led the reader to believe, the South China Sea is a region of immense economic and strategic importance. Geographically situated at the heart of Southeast Asia, it serves as one of the world’s most critical maritime trade routes, facilitating approximately 21% of global trade [8]. The economic implications of this passage cannot be understated; it is estimated to harbor around 105 billion barrels of hydrocarbon reserves and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, resources vital for any nation capable of controlling or accessing them [4]. For countries like China, Vietnam, and the Philippines, the availability of these resources translates into opportunities for economic growth, energy security, and a greater degree of independence from external energy suppliers.

For China, control of the Paracel and Spratly Islands is particularly significant due to the nation’s growing energy demands and reliance on this critical trade route [8]. As the world’s second-largest oil consumer, China’s economic growth relies on secure and direct access to energy imports, 80% of which flow through the South China Sea [8]. Control of the islands would allow China to secure its shipping lanes and avoid potential disruptions from other nations, safeguarding its energy and economic security [8]. Additionally, establishing a military presence in these islands grants China strategic depth and the ability to create a defensive perimeter against regional adversaries. With military bases in the Paracels and Spratlys, China can monitor activity in the South China Sea, deter foreign military actions, and reinforce its territorial claims, thereby enhancing both its economic stability and defense capabilities [5].

Vietnam and the Philippines, on the other hand, share a strong interest in maintaining control over key areas in the South China Sea to preserve their territorial integrity, safeguard vital economic zones, and curb China’s growing influence in the region. Both countries recognize the sea’s immense value for its abundant fisheries, rich natural resources, and strategic shipping lanes, which are essential to their economic sustainability. For nations such as the Philippines and Vietnam, indeed, access to marine resources has become critical for food security [8]. By maintaining control over these areas, they also aim to prevent Beijing from establishing unchallenged military and logistical footholds that could shift the balance of power and infringe on their maritime rights [8].

China’s Strategy: “Cabbage Tactics” and Expanding Presence

China’s contemporary strategy for expansion in the South China Sea is characterized by the use of “cabbage tactics.” This method involves surrounding contested islands with layers of vessels, including military ships, coast guard, and fishing boats, to isolate these areas and prevent other nations from accessing or supplying their outposts [9]. Examples of cabbage tactics include the 2012 encirclement of Scarborough Reef in the South China Sea, contested by the Philippines; the 2013 presence near Ayungin Island, also claimed by the Philippines; the installation of a CNOOC oil rig within Vietnam’s claimed Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ); and the 2019 activity near Pagasa Island in the South China Sea [9].

Since 2013, China has also accelerated dredging activities, creating over 3,200 acres of artificial land in the Spratlys while constructing airstrips, radar installations, and missile facilities. These artificial islands have amplified China’s military capabilities to project power across the South China Sea [10].

In addition to the mentioned maneuvers, China has developed diplomatic channels and economic incentives to persuade ASEAN nations to avoid multilateral confrontations and to negotiate bilaterally, where China’s influence is more pronounced. This approach not only allows China to manage conflicts on a case-by-case basis but also helps mitigate the complexities that arise from engaging multiple parties simultaneously. By discouraging neighboring nations from inviting external actors in negotiations, particularly the United States, China aims to maintain its dominance in the region [8].

The economic ties cultivated with regional countries, in this regard, serve not only as tools for diplomacy but also as means to exert pressure during disputes. For instance, China has recently restricted imports from the Philippines during times of increased tensions over territorial claims [8].

The Philippines and Vietnam: Responding to Regional Pressures

In order to enhance its military capabilities in the South China Sea, the Philippines has actively implemented the Comprehensive Archipelagic Defence Concept (CADC), aiming to fortify its territorial claims and face rising tensions with China. Central to this initiative is the US$56 million upgrade of Thitu Island, also known as Pag-asa, which includes the extension of its airstrip to 1.5 kilometers [11]. This improvement allows larger aircraft to land, increasing logistical support for Philippine troops stationed in this remote area. As Rear Admiral Roy Vincent Trinidad (the Philippine Navy spokesman) emphasized, this effort reflects a strong focus on safeguarding the nation’s territorial claims and its 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) [11].

Simultaneously, Vietnam is rapidly advancing its own strategy in the Spratly Islands by reclaiming land and improving its military outposts. Within just five months, Vietnam has reportedly reclaimed over two square kilometers and is upgrading 11 of the 29 features it controls [12].

The Philippines and Vietnam have recognized the necessity of cooperation in the face of China’s assertive strategy. In August, the two nations reached an agreement to boost collaboration on maritime security [13]. However, experts like Nguyen Khac Giang suggest that the current collaboration is largely symbolic, as mutual support is complicated by differing national strategies, historical experiences, and varying levels of military capabilities [13].

The Philippines, under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., adopted a more confrontational approach to China. Recent developments have been marked by vocal condemnation of aggressive tactics employed by the Chinese Coast Guard against its vessels and closer military cooperation with allies, especially the United States [14]. In contrast, Vietnam has historically prioritized stability and economic development, often preferring diplomatic channels to resolve disputes. While Vietnam has made significant strides in increasing its presence in the Spratly Islands, it has maintained open lines of communication with China to avoid escalating confrontations [14]. This cautious approach can be observed in its reluctance to conduct joint military exercises that might provoke China or disrupt economic ties [14].

Moreover, the disparities in military capabilities between the two nations further complicate their cooperation. Vietnam features a more robust maritime presence and a larger fleet, while the Philippines, facing budget constraints and limited naval capabilities, relies heavily on U.S. military support for defense.

The Role of the United States and Japan

The United States and Japan play a significant role in the ongoing dispute. U.S. interests in the region are deeply rooted in protecting freedom of navigation, supporting security, and maintaining economic stability [8]. Given that the South China Sea is a critical route for global trade and military operations, Washington has repeatedly challenged China’s territorial claims by conducting freedom of navigation-operations aimed at safeguarding international law [8]. Furthermore, in light of China’s escalating assertiveness, the US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty (which obligates the U.S. to defend the Philippines in the event of an armed attack) has gained renewed importance.

Japan has recognized the importance of regional security in the South China Sea as part of its broader national defense strategy. In response to China’s maritime expansion, Japan has strengthened its defense ties with the Philippines and Vietnam through joint military exercises, arms transfers, and capacity-building initiatives [16].

The recent joint naval exercises organized by the Philippines on April 7, which included participation from the United States, Japan, and Australia, reflect this growing collaboration [16].

Obviously, U.S. and Japanese support is not only intended to protect regional actors’ territorial claims; aid also serves as a countermeasure to balance China’s growing hegemony in the region and slow down its expanding influence.

Rising Concerns

The disputes in the Spratly Islands add to the existing volatility in Southeast Asia, where China’s assertive territorial claims intensify regional tensions. This situation, mirrored in other parts of East Asia, raises security concerns.

Recently, China has increased its military intimidation toward Taiwan, conducting aggressive aerial and naval maneuvers such as frequent air sorties near Taiwan and simulated blockade exercises [17]. This escalation has raised alarms in Washington, given the U.S. commitment to Taiwan’s defense under its policy of strategic ambiguity. Analysts worry that any miscalculation could lead to a direct conflict between the United States and China [17], drawing both nations closer to the Thucydides Trap. This refers to the historical pattern where a rising power’s challenge to a dominant power leads to tension, often resulting in war [20].

In parallel, tensions between China and Japan have also grown, particularly in the East China Sea. On August 26, the People’s Liberation Army violated Japanese airspace for the first time in over fifty years, with a reconnaissance aircraft coming within 12 nautical miles of Japan’s Danjo Islands [18]. Although the area is uninhabited, this incident further strained relations and angered Tokyo. Some analysts suggest that these provocations may be strategically timed to disrupt diplomatic negotiations, such as the recent visit by U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan to Beijing [19].

As mentioned, the overall situation in the region is becoming increasingly dangerous. Although tensions in the Spratly Islands are unlikely to lead to immediate escalation, the unresolved territorial claims complicate diplomatic relations among neighboring nations, creating a backdrop of constant friction that hinders regional stability. This landscape raises serious concerns about the potential for conflict, underscoring the urgent need for effective diplomatic efforts to address these challenges.

Edited by Justine Peries.

References

[1] “Philippines says Chinese laser temporarily blinded ship crew – DW – 02/13/2023.” DW, 13 February 2023, https://www.dw.com/en/philippines-says-chinese-laser-temporarily-blinded-ship-crew/a-64681740.

[2] MISTREANU, SIMINA, and JIM GOMEZ. “South China Sea: Chinese vessel, Philippine supply ship collide.” AP News, 17 June 2024, https://apnews.com/article/china-philippines-second-thomas-shoal-collision-navy-8c14b945066967189b01d701b17c10ae.

[3] “Territorial disputes in the South China Sea.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Territorial_disputes_in_the_South_China_Sea.

[4] Zhang, Anson. “Why does China claim almost the entire South China Sea?” Al Jazeera, 24 October 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/10/24/why-does-china-claim-almost-the-entire-south-china-sea.

[5] Pletcher, Kenneth, and Eugene C. LaFond. “Spratly Islands | Disputes, Geography & History, South China Sea.” Britannica, 31 October 2024, https://www.britannica.com/place/Spratly-Islands.

[6] “What is the South China Sea dispute?” BBC, 7 July 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-13748349.

[7] Maizland, Lindsay. “Timeline: China’s Maritime Disputes.” Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/timeline/chinas-maritime-disputes.

[8] STRATEGIC ANALYSIS A strategic analysis of the South China Sea territorial issues, https://www.mod.go.jp/msdf/navcol/assets/pdf/topic049_02.pdf. Accessed 12 November 2024.

[9] “Cabbage tactics.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cabbage_tactics.

[10] “China Tracker.” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/island-tracker/china/.

[11] Maitem, Jeoffrey. “Philippines strengthens South China Sea strategy with US$56 million Thitu Island upgrade.” SCMP, 27 October 2024, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/economics/article/3283913/philippines-strengthens-south-china-sea-strategy-us56-million-thitu-island-upgrade?module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article.

[12] Chen, Alyssa. “South China Sea: Vietnam’s growing Spratly outposts spark flashpoint concern in China.” SCMP, 25 October 2025, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3283834/south-china-sea-vietnams-growing-spratly-outposts-spark-flashpoint-concern-china?module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article.

[13] Walker, Tommy. “South China Sea: Philippines, Vietnam deepen defense ties – DW – 09/10/2024.” DW, 10 September 2024, https://www.dw.com/en/south-china-sea-philippines-vietnam-deepen-defense-ties/a-70181293.

[14] Siow, Maria. “Philippines sides with Vietnam in South China Sea dispute, hoping it will ‘return the favour.’” SCMP, 9 October 2024, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3281661/philippines-sides-vietnam-south-china-sea-dispute-hoping-it-will-return-favour?module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article.

[15] “Japan–Philippines defence deal reflects regional security dynamics.” East Asia Forum, 9 September 2024, https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/09/09/japan-philippines-defence-deal-reflects-regional-security-dynamics/.

[16] “Philippines, U.S., Australia and Japan hold joint military drills in disputed South China Sea.” The Japan Times, 7 April 2024,

[17] “What’s behind China-Taiwan tensions?” BBC, 14 October 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-34729538.

[18] Dahm, Michael. “Connecting the Dots on China’s Airspace Violation.” Air & Space Forces Magazine, 29 August 2024, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/commentary-china-japan-airspace-violation/.

[19] “Sino-Japanese Tensions Will Escalate in the East China Sea.” BIPR, https://bipr.jhu.edu/BlogArticles/32-Sino-Japanese-Tensions-Will-Escalate-in-the-East-China-Sea.cfm.

[20] Mukherji, Mithlesh Jayas. “US-China Power Struggle or Peaceful Coexistence: Will it Avoid the Thucydides Trap?” E-International Relations, 1 August 2024, https://www.e-ir.info/2024/08/01/u-s-china-power-struggle-or-peaceful-coexistence-will-it-avoid-the-thucydides-trap/.

[Cover Image] Photo of “China’s maritime claim (red) and UNCLOS exclusive economic zones (blue) in the South China Sea” by Goran tek-en licensed under Creative Commons.

Leave a comment