By Alix Poncet.

Since Alan Turing first questioned, in 1950, whether a machine could “think,” artificial intelligence (AI) has evolved from a mere scientific curiosity to an omnipresent technology [1]. Defined as the set of methods enabling machines to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence (such as perception, reasoning, and decision-making), AI serves as a major lever for societal transformation [1]. Among its most notable developments is so-called “generative AI,” which relies on sophisticated algorithmic models—often based on deep neural networks—to generate text, images, music, or even videos from pre-existing data [2].

This capacity for creation raises fundamental questions about the boundary between humans and machines. The Turing test, proposed in 1950, offers a pertinent conceptual framework: if, during a conversation, a human can no longer distinguish between a machine and a person, then the machine is considered “intelligent” [3]. Thanks to their remarkable realism, the most recent AI models seem to be approaching, if not surpassing it. This evolution challenges our long-standing understanding of intelligence, traditionally regarded as an exclusively human trait. Scenarios once confined to science fiction—such as those portrayed in Alex Garland’s Ex Machina—are no longer purely imaginary: the apparent autonomy of AI has become a tangible reality [4].

The rise of these technologies has unfolded in a digital landscape where English dominates nearly half of all online content, leaving French with a mere 5% share [5]. This asymmetry benefits major American tech players and subtly propagates norms and values rooted in an Anglophone cultural framework under the guise of algorithmic neutrality. This dynamic represents a novel form of soft power, aligning with the concept developed by Joseph Nye [6]: an ability to seduce and influence non-coercively, shaping a particular worldview through the lens of AI. Even if this influence is not always explicitly intended by tech giants, it far exceeds what figures like Allen Dulles or Edward Bernays—the pioneer of modern propaganda—could have envisioned [7].

Within this context, linguistic diversity faces increasing pressure toward homogenisation. With its rich philosophical, political, and literary tradition, the French language risks marginalisation. Yet, it remains the language of diplomacy, the Enlightenment, human rights, and great thinkers such as Descartes, Rousseau, and Montesquieu. Its vitality extends beyond culture alone: it embodies a critical heritage and a spirit of debate essential to pluralism. This raises a crucial question: who holds the power to “define who we are,” as Raphaël Llorca’s notion of “narrative sovereignty” suggests? [8] Dominant AI systems, trained on vast English-language corpora, could impose a singular intellectual model at the expense of linguistic and cultural diversity.

This trend raises important ethical concerns. The algorithmic biases that arise from the dominance of English can foster a kind of ‘Anglocentrism’ which influences our ways of thinking and understanding the world. Research by Safiya Umoja Noble has demonstrated that the underrepresentation of specific communities in data sets reinforces stereotypes [9]. If we are to safeguard ‘cognitive freedom’ or the ‘right to mental self-determination’ in the digital age, it is imperative to ensure diversity in training data. Otherwise, an intellectual and cultural standardisation, where the perspectives and values of English-speaking cultures dominate, could ultimately impoverish democratic debate and limit the diversity of ideas in AI systems.

As AI grows in influence, its role in shaping public opinion and information necessitates appropriate governance. Disinformation campaigns leveraging generative AI—particularly in the context of the war in Ukraine or electoral processes [10] —illustrate how these technologies can manipulate collective perceptions. Bruno Patino [11], in his work on “infobesity,” underscores how information overload erodes critical thinking, while David Colon [10] highlights AI’s role in amplifying propaganda mechanisms. The question is no longer merely how to regulate AI but rather which actors—states, multilateral organisations, corporations—should be mobilised according to the principles of transparency and sovereignty.

The AI Action Summit, scheduled to take place in Paris in February 2025, must bring these issues to the forefront. More than ever, defining an international cooperation framework that balances technological innovation with preserving linguistic and cultural diversity is essential. In this regard, Francophone countries would benefit from collaborating to strengthen their position in AI development just as they consider common economic alliances. The European tech conference VivaTech, hosted in Paris with Canada as this year’s guest country, offers an additional opportunity in this direction. France should also seize this moment to deepen partnerships with other Francophone stakeholders and promote AI specifically adapted to the French language, which boasts 320 million speakers today and is projected to reach 715 million by 2050 [12].

A cooperative strategy that creates more balanced datasets and supports local research institutions could bolster the presence of French and other Francophone languages in AI-generated text and recommendation models.

AI is no longer merely a tool for competitiveness; it has become a crucial instrument of power and influence, reshaping global geopolitical dynamics. A recent example underscores this growing strategic significance: the United States’ decision, announced in late 2022 and reinforced in 2023, to restrict exports of advanced AI chips to China [13] [14]. The sudden emergence of DeepSeek in early 2025—a new Chinese competitor whose model reportedly outperforms its Western counterparts while reducing costs—demonstrates how swiftly these power dynamics can shift [15]. Marc Andreessen, a prominent Silicon Valley venture capitalist, has even likened this moment to “Sputnik,” evoking the scientific competition of the Cold War era.

Simultaneously, AI model performance heavily depends on access to reliable, diverse, and multilingual data. Recent partnerships between major AI providers highlight this reality: Associated Press and Google (Gemini) on one side, AFP and Mistral AI on the other, alongside the collaboration between Le Monde and OpenAI [16]. Each entity aims to capitalise on rich journalistic content and archival resources, which provide a competitive edge. Likewise, the Francophone world has a strategic role in offering multilingual datasets that valorise its cultural richness and historical tradition of critical thinking.

In this context, French President Emmanuel Macron emphasised at the Francophonie Summit in Villers-Cotterêts that the Francophone community must serve as the foundation for “a Francophone approach to artificial intelligence” [17]. Establishing the Center for Language Technology Reference is a first step toward preserving linguistic diversity in the AI era. France is also betting on Mistral AI, a promising young unicorn, to assert its technological standing against the GAFAM giants.

However, this raises a broader question: can Europe unite and assert its influence in the global AI arena? Mario Draghi’s analyses, calling for a strong and swift European response, align with the ambitions expressed by Ursula von der Leyen, who has underscored the necessity of massive investments and the development of common standards, such as the “competitiveness compass” and the AI Act [18]. Yet, in contrast to the assertive U.S. stance—embodied by Donald Trump’s pledge to invest $500 billion in AI over four years—the European Union has struggled to scale up its efforts [19].

If AI is to become one of the pillars of sovereignty in the 21st century, Europe must overcome internal divisions, clarify its innovation framework, and mobilise funding commensurate with its ambitions. Despite France’s transatlantic collaboration in technological development and financing with the NATO body DIANA [20], France and Europe are actively pursuing strategic autonomy, seeking to reduce dependence on the United States while strengthening their own capabilities. This desire for sovereignty isn’t starting from scratch: France and the EU already possess globally renowned engineers, world-class research centres, and universities that rival the best American institutions. These assets provide a solid foundation for developing cutting-edge technologies and fostering innovation on a global scale.

What remains to be achieved is greater coherence and enhanced cooperation among member states to realise this potential fully. Far from mere technical advancement, AI has already become a battleground for political and cultural power. The time has come for Europe to seize this opportunity and assert a unique path—one that upholds pluralism and universal values—so that the coming digital revolution embodies the interests and ideals of a united continent.

Edited by Justine Peries.

References

[1] Goutefangea, P. (2017). Alan Turing et l’intelligence artificielle : le “ jeu de l’imitation ” et “ l’IA forte ”. https://hal.science/hal-01330278v2/document?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[2] WIPO. (2025). Patent Landscape Report – Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI). Patent Landscape Report – Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI). https://www.wipo.int/web-publications/patent-landscape-report-generative-artificial-intelligence-genai/en/index.html

[3] Damman, M. (2024, October 4). Reverse Turing test : des IA peuvent-elles identifier un humain parmi elles ? – L’ADN. https://www.ladn.eu/tech-a-suivre/reverse-turing-test-des-ia-peuvent-elles-identifier-un-humain-parmi-elles/

[4] Sagnard, A. (2024, July 28). De “Her” à “Ex Machina”, le charme troublant de l’incarnation de l’IA au cinéma. https://www.nouvelobs.com/culture/20240728.OBS91736/de-her-a-ex-machina-le-charme-troublant-de-l-incarnation-de-l-ia-au-cinema.html

[5] Statista. (2024). Most used languages online by share of websites 2024 | Statista. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/262946/most-common-languages-on-the-internet/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[6] Nye, J. S. (1990). Soft Power. Foreign Policy, 80(80), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.2307/1148580

[7] Aumercier, S. (2007). Edward L. Bernays et la propagande. Revue Du MAUSS, 30(2), 452. https://doi.org/10.3917/rdm.030.0452

[8] Campion, E. (2024, October 17). Raphaël Llorca : “Les marques sont devenues l’une des principales sources d’imaginaires territoriaux.” https://www.marianne.net/agora/entretiens-et-debats/raphael-llorca-les-marques-sont-devenues-lune-des-principales-sources-dimaginaires-territoriaux

[9] Snow, J. (2018, February 26). Bias already exists in search engine results, and it will only get worse. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2018/02/26/3299/meet-the-woman-who-searches-out-search-engines-bias-against-women-and-minorities/

[10] Colon, D. (2024). Le rôle de l’intelligence artificielle dans la guerre de l’information. Revue Défense Nationale, n° 873(8), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.3917/rdna.873.0007

[11] Patino. (2023, January 17). “S’informer, à quoi bon ?” de Bruno Patino. France Inter. https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceinter/podcasts/les-80/les-80-de-nicolas-demorand-du-mardi-17-janvier-2023-4196580

[12] Alliance des patronats francophones. (2025, February 4). ALLIANCE DES PATRONATS FRANCOPHONES. ALLIANCE DES PATRONATS FRANCOPHONES. https://www.patronats-francophones.org/

[13] Reuters Staff. (2024, December 3). US targets China’s chip industry with new restrictions. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/us-targets-chinas-chip-industry-with-new-restrictions-2024-12-02/

[14] Booth, H. (2025, January 8). How China Is Advancing in AI Despite U.S. Chip Restrictions. TIME; Time. https://time.com/7204164/china-ai-advances-chips/

[15] Duffy, C. (2025, January 29). Why DeepSeek could mark a turning point for Silicon Valley on AI. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/01/29/tech/deepseek-silicon-valley-ai/index.html

[16] Bradshaw, T. (2025, January 16). Mistral signs AFP deal for fact-based chatbot in riposte to “free speech” rivals. @FinancialTimes; Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/9200122d-bb4d-4f13-b9db-4991815026b4

[17] Elysee. (2024, October 4). XIXe Sommet de la Francophonie : première journée à Villers-Cotterêts. Elysee.fr. https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2024/10/04/xixe-sommet-de-la-francophonie-premiere-journee-a-villers-cotterets

[18] European Commission. (2025). An EU Compass to regain competitiveness and secure sustainable prosperity. European Commission – European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_339

[19] Arnaud Leparmentier. (2025, January 22). Stargate, Trump’s $500 billion project to boost artificial intelligence. Le Monde.fr; Le Monde. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/economy/article/2025/01/22/stargate-trump-s-500-billion-project-to-boost-artificial-intelligence_6737299_19.html

[20] NATO. (2024). Stratégie OTAN pour l’intelligence artificielle – synthèse pour mise en lecture publique. NATO. https://www.nato.int/cps/fr/natohq/official_texts_227237.htm?selectedLocale=en

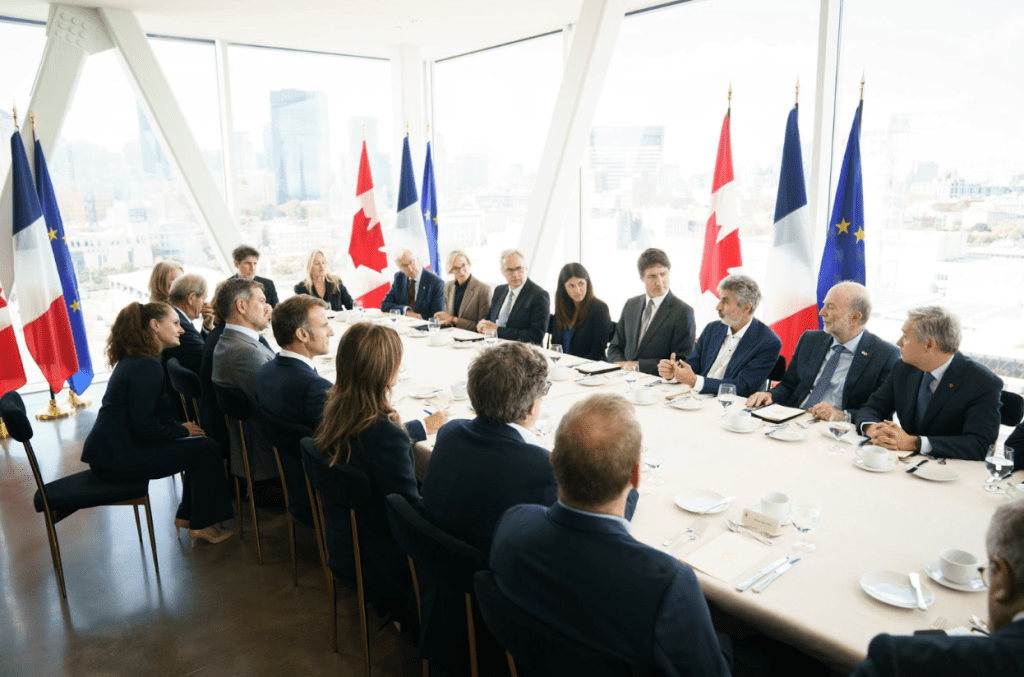

[Cover Image] Photo of Anne Bouverot – AI luncheon in Montreal at the invitation of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau during President Emmanuel Macron’s state visit, alongside Yoshua Bengio, Valérie Pisano, Yann LeCun, Martin Kon, Julien Billot, Serge Godin, Hélène Desmarais, Roland Lescure, Stephen Toope, and Giuliano da Empoli.

Leave a comment