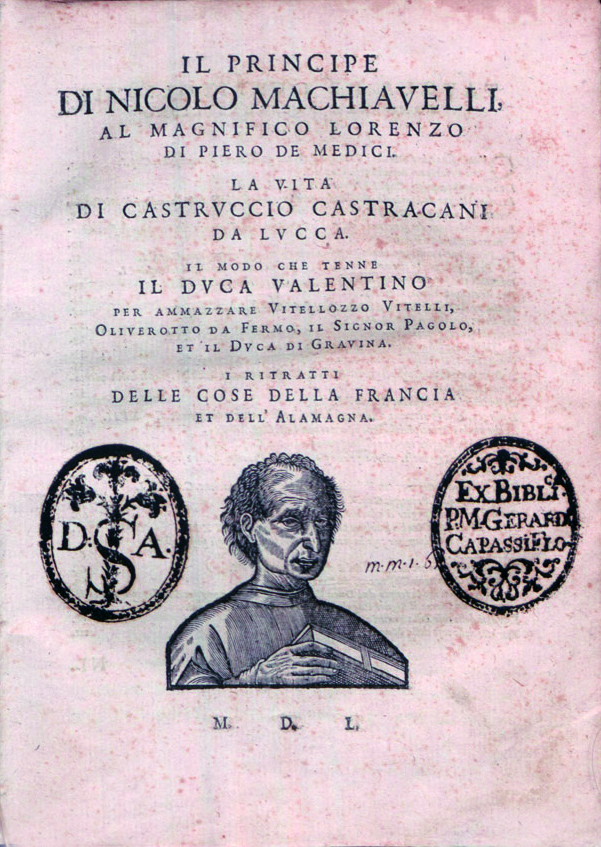

Power, a strong word, one people fear or often associate with something negative. Yet, power is in everything: in business, politics, human relationships, and in nature; our entire system is built upon it. Since primitive times there has always been the so-called “law of the strongest”, where the strongest individual imposes their will on the weaker, leading to the subordination of the less powerful. Power has different shapes, it evolved throughout history, but it remains impossible to escape. Throughout history, the concept of power has been a frequent topic of discussion and debate among influential thinkers. To name a few: Sun-Tzu, who wrote The Art of War (5th century BC), Niccolò Machiavelli, who composed the infamous The Prince (1513) or, more recently, Robert Greene’s The 48 Laws of Power (1998) [1][2], with the Florentine philosopher as a source of inspiration. To me, it is especially Machiavelli’s and Greene’s works that are key to understanding the notion of power and how it plays a predominant role in our existence. This is why I will aim at exploring those books and how they resonate with each other, in the hopes that they can help us embrace this inescapable force that is power. Beyond the topic they both explore, the two books resonate also with each other because of their highly disruptive nature.

Niccolò Machiavelli lived in the XVI century, a turbulent period in the history of the Italian peninsula—in fact it was fragmented into different States [3]. There was no unique ruler or government, and the land was constantly torn apart by wars and foreign domination. It is in such a complicated context that he published a controversial work, which was eventually censored by the Church in 1559 and included on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of prohibited books) due to its unsettling ideals. Machiavelli was born in Florence. From childhood, he had access to his father’s personal library, which was rich in works by the great classics: he developed a special passion for ancient history by reading authors such as Cicero, Thucydides, Livy, Polybius, and Plutarch. When he reached adulthood, he served in the Florentine Republic as a secretary and diplomat. His career peaked when he was appointed Vice-Chancellor, allowing him to engage with important European powers. Unfortunately, in 1512, Machiavelli was imprisoned after being falsely accused of conspiracy. Shortly after, he was released, but semi-exiled and barred from political life. He then decided to retire to his countryside house in Sant’Andrea in Percussina, devoting himself to literature, where he composed The Prince and his other major works.

His experiences were fundamental for the composition of his book. In fact, The Prince is not a theoretical manuscript, as from the beginning he made it clear that his interest did not lie in abstract ideas, but in real-world politics. He wrote about how power is — not how it should be. His goal was to depict what successful rulers did, and to underline the importance of following their example. Like an archer does when he throws an arrow, he shoots high in the sky even though the target is low and far from him. He follows a trajectory, like a new prince follows the trajectory traced by the great leaders. Throughout the book, Machiavelli addressed different themes, such as: what a princedom is, what the differences between weak and strong armies are, which roles Fortune and Virtue play in the game of politics. Yet, the real innovation was the insight Machiavelli gave us into the psychology of a leader.

“A ruler mustn’t worry about being labelled cruel when it’s a question of keeping his subjects loyal and united; using a little exemplary severity, he will prove more compassionate than the leader whose excessive compassion leads to public disorder, muggings and murder.” [1]

In a nutshell, Machiavelli states here that it is better to be feared rather than be loved. This conception can sound cynical, but we must not forget that, above all, a ruler has two main goals: maintaining his power and granting prosperity to his people, and all of his actions depend on this. That is why it is incorrect to say that the philosopher’s vision can be summarized in the sentence: “The end justifies the means.” First off, he never stated that in his book. Secondly, the Prince cannot act immorally; power is not more important than the condition of his country and of his people. A leader depends on his subjects as much as his people depend on him. All this put Machiavelli’s ideas far ahead of his time, which is why he was often misunderstood—and still is today, if he is not studied accurately.

Centuries later, Robert Greene recognized the importance of Machiavelli’s work, and by drawing on these ideas, he wrote about power, but in a different way. The 48 Laws of Power is similar to a handbook on power dynamics. The events reported as examples are very diverse, and cover a period of more than three thousands years; yet the red thread stays the same: the essence of power and strategy, and how to master them. This book can be seen as a sum of all the wisdom gathered from strategists such as Claus von Clausewitz, or statesmen like Bismark, but also seducers like the infamous Casanova. The themes are disparate: Greene does not talk solely about politics, like Machiavelli did in The Prince, but also describes other kinds of dynamics: the ones related to companies, relationships, friendships, business and more. The structure of the book is clear, just like a guide. In the first part there is the summary of all the laws, designed to allow the reader to have a complete overview. The laws are then presented all in the same way, and with a specific method: a “judgment” introduces two events, the first one represents the “observance” of this rule, meanwhile the second describes its “transgression“. Each law concludes with a closing commentary that abstracts the principle taken from the practical examples, envisioning it within a broader framework of human behaviour. This clear structure and Greene’s straightforward language allow the reader to learn about power in a general, but complete way. Although at first some laws may appear difficult to apply, in time it becomes clear that each law is in reality interrelated. Readers do not have to endorse everything said in this book, instead they have to become aware. The 48 Laws of Power encourages awareness of the dynamics of influence, authority, and manipulation that exist in different social settings, from politics to intimate relationships. Ultimately, this book works as a guide, but also as a mirror that reflects the reality of human behaviour, and it equips readers with the right tools to navigate the complexity of our world. This concept can be summarized in one of Greene’s quotes:

“If the game of power is inescapable, better to be an artist than a denier or a bungler.”[2]

If power is on one side of the coin, strategy stands on the other. They are interrelated, since strategy is both a tool and an expression of power. Power itself is like a game, or as Greene says in his book “power is more godlike than anything”[2]. It is not a skill, or a virtue that comes naturally, to win at this game you must know how to move, and to know how to make the right moves you must have a clear strategy. Greene summarizes the rules of this game at the start of the book, in a preface. Among them, he underlines a few aspects: the importance of concealing emotions, for they can make you vulnerable and cloud your reason; the use of appearances as weapons (masks are inevitable and all human interaction requires some degree of deception); and the exercise of patience, described by Greene himself as a “shield”[2] that prevents us from making wrong decisions.

In the end, both Machiavelli and Greene, even if in different ways, reveal that power does not lie in brute force but in subtle mastery. On one hand, Machiavelli demonstrates that politics cannot be reduced to strict formulas: maintaining power depends on a shifting balance of fortune, personal character and situations. The only true way to reach long-term power would be to have everything under control and adapt perfectly at every circumstance, but such a scenario is utopian. On the other hand, Greene managed to create a far more practical guide that tries to uncover the secrets and masks of the society. These two works help us to decode the strategies others are already playing by, and that many try to ignore, preferring the illusion of an innocent reality. The decision is now ours: do we want to be blind forever, or is it time to step out of the cave, as Plato would have said, and finally face the truth?

Edited by Justine Dukmedjian.

An earlier version of this article stated that Italy pre-unification was composed of “republics”, which did not reflect the other types of states such as monarchies, papal, duchies. “States” was therefore replaced to encompass all of them.

References

[1] “Machiavelli, The Prince.pdf.” apeiron, 21 May 2015, https://apeiron.iulm.it/retrieve/handle/10808/4129/46589/Machiavelli%2C%20The%20Prince.pdf.

[2] Greene, Robert, and Joost Elffers. The 48 Laws of Power (A Joost Elffers Production). Profile, 2000.

Machiavelli, Niccolò. Il principe. Testo originale e versione in italiano contemporaneo. Edited by Martina Di Febo, translated by Martina Di Febo, Rizzoli, 2013.

[3] Machiavelli, Niccolò, and Santi Tito. “Niccolò Machiavelli e la politica senza scrupoli.” Storica National Geographic, 23 June 2020, https://www.storicang.it/a/niccolo-machiavelli-e-politica-senza-scrupoli_14837. Accessed 31 August 2025.

[Cover Image] Photo credits via Wikipedia Commons.

Photo 1: Niccolò Machiavelli Principe Cover Page – BNCF, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11844670

Leave a comment