Piracy, in popular imagination, is either a relic of skull-and-crossbones flags, cutlass, and parrots, or confined to the digital world. Yet, in 2025, maritime piracy has returned as a harsh reality for shipowners, seafarers, and insurers. The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) recorded 90 incidents in the first half of 2025, a near 50% increase over the same period the previous year [1]. Far from the Caribbean fantasies of popular culture, these incidents mainly span the Horn of Africa, the Gulf of Guinea, and the Singapore Strait, reminding policymakers that piracy remains a living and evolving threat. The issue is not new. The early 2010s saw Somali piracy dominate global security debates , while the Gulf of Guinea became notorious for kidnappings in the late 2010s [2] [3]. By the early 2020s, the problem appeared contained. Yet complacency has proven costly. With the Red Sea crisis, shifting shipping routes, and renewed coastal instability, piracy has staged a comeback [4].

This article explores the return of piracy in three steps. First, by clarifying what is considered “piracy” in 2025 and providing necessary context. Second, by tracing the main regional hotspots where the threat is concentrated and where it has been (somewhat) rooted. And finally, by analysing the root causes that explain why piracy, in all its forms, continues to haunt global shipping lanes, and why can we notice a new surge of violence.

When discussing the “return” of piracy in the 2020s, precision is key. In international law and contemporary maritime security, the concept is far more constrained and technical than is commonly thought. The legal anchor is Article 101 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which defines piracy as “any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship […] on the high seas, against another ship […] or against persons or property on board such ship” [5]. This definition matters because it restricts piracy to the high seas, outside of any State’s territorial waters. Attacks inside territorial waters fall instead under the category of “armed robbery against ships”. It is the responsibility of the coastal State, as defined by the International Maritime Organisation in its resolution A.1025(26) of December 2 2009: “any illegal act of violence or detention or any act of depredation, or threat thereof, other than an act of piracy, committed for private ends and directed against a ship or against persons or property on board such a ship, within a State’s internal waters, archipelagic waters and territorial sea or any act of inciting or of intentionally facilitating an act described above.” [23]. This distinction may seem semantic, but it structures the way incidents are recorded and treated, and entails a very different framework to answer to what are, basically, the same acts or intent [6]. For example, in the case of the gulf of Guinea, where attacks against ships happen most often in territorial waters (and is as such considered armed robbery against ships if you followed well), such cases diminished only after the reinforcement of Nigeria’s protection of sea lanes. In contrast, piracy in Somalia happens far from any coast, often deep in international waters, which facilitated international intervention [7]. The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) Piracy Reporting Centre, based in Kuala Lumpur, acts as the global clearinghouse for such reports. Its annual and quarterly reports classify incidents according to whether they occurred on the high seas (piracy) or within territorial waters (armed robbery). In practice, much of what makes the headlines as “piracy” – for example the illegal boardings in the Singapore Strait (which constitutes up to 63% of incidents in 2025) – technically falls under the armed robbery category.

From a statistical standpoint, piracy remains well below its historical peak in the early 2010s, when Somali groups were hijacking dozens of vessels per year and holding hundreds of seafarers hostage. But the IMB’s recent figures are troubling. The 2024 annual report recorded 120 incidents, slightly up from 115 in 2022, and warned of a “disturbing resurgence of Somali piracy after years of dormancy” [8]. Violence, in particular, is climbing: 126 seafarers were taken hostage in 2024, compared to 73 the previous year, and the use of firearms increased by 73% [8]. In the first half of 2025 alone, the IMB noted 90 incidents, a nearly 50% increase compared with the same period in 2024 [1]. The Singapore Strait is of particular concern, as ships crossing it account for around 30% of international trade [4]. To speak of a “return of piracy” in 2025 therefore means acknowledging both the hard numbers of renewed incidents and the symbolic weight piracy carries in global security debates. The return of piracy happens concurrently with a renewed use of the sea for illegal operations, such as Russia’s techniques to circumvent sanctions on its imports, as has been treated by the ESCP International Politics Society in this article.

The global geography of piracy in 2025 is far from being uniform. Instead, incidents are concentrated in a handful of maritime corridors where economic vulnerability, weak governance, and/or heavy shipping traffic intersect. While the overall number of global incidents remains far below the levels seen a decade ago, the distribution and character of piracy today reveal a complex landscape.

For much of the 2010s, Somali piracy was seen as the epitome of maritime insecurity. At its height in 2011, Somali groups launched 237 attacks, holding more than 700 hostages at once and extracting ransoms estimated at $146 million [9]. The combination of naval patrols, armed guards on ships, and capacity-building initiatives largely suppressed this threat by 2017 [3]. Yet the apparent end of Somali piracy was deceptive. In December 2023, pirates seized the bulk carrier MV Ruen, the first successful hijacking of a major commercial vessel in the region since 2017. The ship and its crew were held for more than three months before being freed in a dramatic operation by the Indian Navy in March 2024 [10]. This single case signalled that neither the networks, nor the motives for piracy had disappeared, but merely gone dormant after important international efforts. The resurgence has continued into 2025, with multiple reports of Yemeni fishing boats and smaller vessels being seized and used as “motherships”, platforms that allow pirates to extend their range far into the Indian Ocean [4]. The Red Sea crisis has exacerbated the risk: Houthi attacks on commercial shipping have forced many vessels to reroute around the Cape of Good Hope, pushing more traffic through waters adjacent to Somalia [11]. As a result, the Somali coastline is once again becoming a theatre of opportunity for pirate groups.

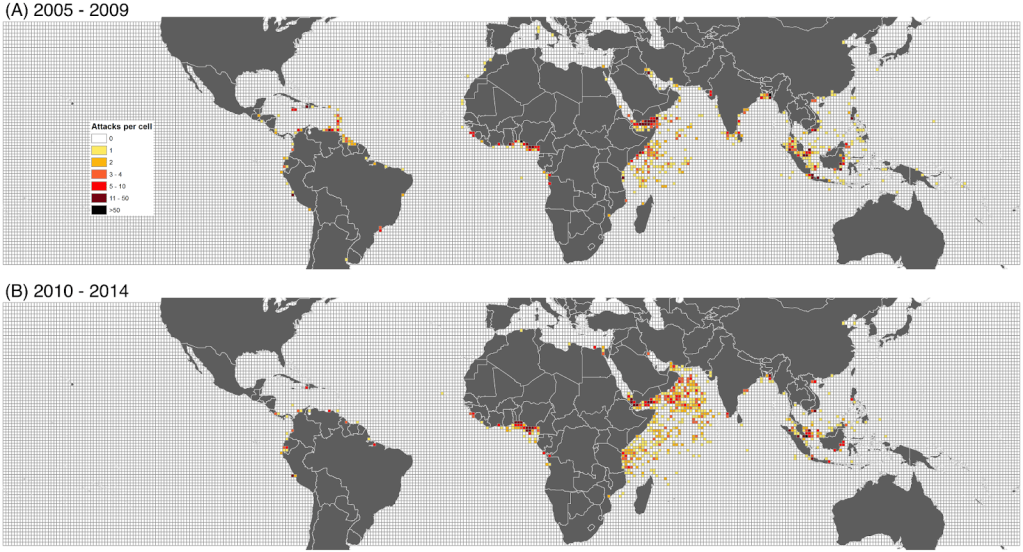

In the following map, we can observe how the fight against Somali piracy diffused the attacks from the Gulf of Oman where they were concentrated into the Arabian Sea. One can also notice the important diminution of piracy in the Caribbean between 2008 et 2017, the result of efficient multilateral cooperation in the region [27]. Modern piracy in the Caribbean is mostly linked to drugs : cargo ships are attacked for drug-filled containers and perpetrators look for these packages, either having found the information or that it was handed to them. Sometimes, the ship is even used as a location where drugs can be handed over for cross-borders dealing [27].

Raj M. Desai ,George E. Shambaugh : Piracy incidents from the consolidated ASAM-GISIS database, overlaid with a 1° × 1° gridded-cell layer. A: 2005-2009. B: 2010-2014. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246835.g001

If Somalia dominated piracy headlines in the early 2010s, the Gulf of Guinea claimed that title in the late 2010s and early 2020s. In 2020, the region accounted for over 95% of all global crew kidnappings, with 130 seafarers taken hostage in 22 separate incidents [20]. Attacks often involved heavily armed groups launching from the Niger Delta, sometimes holding hostages for weeks until ransom payments were arranged. Since then, robust naval interventions, including Nigeria’s Deep Blue Project (launched in 2021) and the EU-supported Gulf of Guinea Inter-Regional Network (GoGIN), have significantly reduced incidents [24] [25] [26]. The IMB recorded only 19 attacks in the region in 2022 and 21 in 2023 [13] [14]. Yet the danger remains acute: the Gulf of Guinea continues to be the world’s most dangerous hotspot for crew kidnappings, and early 2024 saw a modest rise, with 21 incidents in the first half of the year compared to 14 in the same period of 2023 [8].

Piracy in West Africa is distinguishable not just by its frequency but also by its severity. Unlike opportunistic thefts elsewhere, attacks here are often violent and systematic. They reflect the deeper political economy of the Niger Delta, where oil theft, armed militancy, and corruption blur the line between piracy and insurgency [15].

If Somalia and the Gulf of Guinea illustrate the dramatic end of the spectrum, Southeast Asia represents piracy’s chronic face. The narrow and congested Singapore and Malacca Straits, aligned in one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world, carrying an estimated one-third of global trade, have become the epicentre of maritime crime [4]. Incidents there are rarely as spectacular as Somali hijackings or West African kidnappings. Instead, they tend to involve small groups boarding anchored or slow-moving vessels, often at night, to steal fuel, engine parts, or crew belongings. Yet their sheer frequency is striking. In the Singapore Strait alone, reported incidents rose from 34 in 2020 to 55 in 2022 and 57 in 2024 [16]. By 2025, the region accounts for over 60% of all reported global incidents, with the IMB warning of an “alarming persistence of armed robbery in Southeast Asian waters” [1].

The main change is the level of violence. The ReCAAP (Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia) ISC Report 2024 noted that in the Singapore Strait alone, 34 out of 57 incidents involved armed perpetrators, suggesting a shift from petty theft to more organized, dangerous operations [16]. The strait’s geography, with narrow waters, dense traffic, and overlapping jurisdictions, makes it notoriously difficult to police effectively, even with cooperation between Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia [16]. The whole region is an essential gate between Eastern Asia and the West. The importance of the Malacca Strait for China has been evidenced in this previous article.

Beyond these three major hotspots, piracy and armed robbery continue to surface sporadically elsewhere. In South America, particularly off Peru and Venezuela, opportunistic attacks on anchored vessels remain a recurring problem. These incidents are mainly the work of disgruntled fishermen, against Chinese illegal fishing in the case of Peru, or because of economic upheaval in Venezuela [17]. Such incidents, involving fishermen, are also becoming more frequent between Guyana and Suriname, along the territorial waters claimed by both countries [18]. The Indian subcontinent has also seen periodic incidents, with vessels reporting boardings in ports off Bangladesh and India. These cases are fewer and less violent but underscore piracy’s global reach : wherever economic desperation intersects with vulnerable shipping, incidents can occur.

In sum, the geography of piracy in 2025 reflects a dual pattern: spectacular resurgences in former epicenters like Somalia, persistent and dangerous violence in the Gulf of Guinea, and relentless low-level but widespread attacks in Southeast Asia. Each hotspot reflects different dynamics, but together they suggest that piracy is a shifting global phenomenon, adapting to new maritime, political, and economic conditions.

The persistence, and in some regions, resurgence, of piracy cannot be explained solely by opportunistic criminality. Rather, piracy flourishes in environments shaped by structural insecurity, economic precarity, and shifting maritime dynamics. As Yasutaka Tominaga from Hosei University notes, piracy is best understood as part of the broader field of “maritime security assemblages”, where crime, governance, and geopolitical tension intersect [19]. In 2025, four key sets of causes stand out:

1. Geopolitical and Security Vacuums

Piracy thrives in waters where State authority is weak or absent. Nowhere is this clearer than off the Horn of Africa. Following the suppression of Somali piracy after 2012, many international navies drew down their patrols. The EU Operation Atalanta, and NATO’s Operation Ocean Shield both scaled back commitments by the late 2010s [28] [29]. When the MV Ruen was hijacked in late 2023, one shipping security analyst remarked that “the international community had begun to believe Somali piracy was permanently solved” [20]. The pirates knew otherwise.

The Red Sea crisis has worsened piracy in the region. Houthi attacks on commercial shipping beginning in 2023 have forced vessels to reroute around the Cape of Good Hope, increasing traffic near Somalia. Pirates, in turn, have seized the opportunity. As Tominaga observed during the peak of Somali piracy, piracy is “a symptom of insecurity at sea, but also of insecurity on land”[19]. Geopolitical shocks at sea quickly open windows for criminal actors, as was revealed by Tristan McConnell 2009’s Interview with a Pirate for the Global Post [6].

2. Economic and Social Roots

A second cause lies in the political economies of coastal regions. In Somalia and Yemen, decades of State collapse, unemployment, and overfishing have left fishing communities vulnerable. Early Somali pirates often framed themselves as “coast guards” against illegal fishing by foreign trawlers, though ransoms quickly became the dominant incentive [7]. In 2025, similar grievances resurface, and the persistence of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing in Somali waters continues to provide justification narratives for pirate actors [21]. In West Africa, piracy reflects the long-standing instability of the Niger Delta. Groups involved in oil theft and militancy often diversify into maritime kidnapping, creating a lucrative economy of violence. Piracy here is not an isolated phenomenon but part of a “continuum of criminality” linking land-based militancy, oil bunkering, and maritime crime [22].

3. Opportunity Structures

Beyond root causes, piracy depends on opportunities. Chokepoints like the Singapore Strait epitomize this : thousands of vessels pass daily through a 19 kilometer-wide strait, often at low speeds, and within reach of small boats. The sheer density of maritime traffic offers a wide array of targets for would-be attackers [4]. According to the IMB’s 2025 half-year report, “opportunistic boarding of anchored or slow-moving ships remains the single most common form of maritime crime worldwide” [1]. Night-time anchorages, insufficient lighting, and minimal crew watches all increase vulnerability. In this sense, piracy is not only about weak States but also about the physical characteristics of maritime trade: chokepoints, long supply lines, and the difficulty of policing vast seas.

4. Industry and Security Fatigue

Finally, the behaviour of the shipping industry itself plays a role. The dramatic fall in Somali piracy after 2012 led many shipowners to reduce costly protective measures, such as armed guards or best-management-practice protocols [21]. In 2025, evidence suggests a similar cycle. In Southeast Asia, many boardings succeed precisely because vessels no longer invest in deterrents [16]. In West Africa, ransom insurance markets have normalised kidnapping to the point that some companies calculate it as a routine risk of operation [22]. Pirates are adept at exploiting such complacency.

In sum, piracy in 2025 is not reducible to criminal opportunism. It emerges from security vacuums, economic marginalization, structural vulnerabilities of maritime trade, as well as cycles of industry vigilance and fatigue. These causes are deeply intertwined. As long as fragile coastal States, chokepoint vulnerabilities, and complacent industry practices persist, piracy will remain a resilient feature of global maritime security.

The geography of piracy in 2025 is simultaneously familiar and evolving. Somalia’s coastline once again hosts daring hijackings, the Gulf of Guinea remains the epicenter of maritime kidnappings, and Southeast Asia endures a relentless stream of armed robberies. While the number of incidents worldwide remains below the peaks of the early 2010s, the severity and distribution of attacks point to a troubling resurgence in violence. The “return of piracy” since 2020 is thus less a rebirth than a reminder. Pirates adapt, routes shift, and navies redeploy, but the problem never disappears. Instead, it mutates with global insecurity. As long as seafarers face these risks, piracy will remain not a ghost of the past, but a menace of the present.

Edited by Justine Dukmedjian.

References & Footnotes

[1] ICC, IMB Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Report January-June 2025, ICC-IMB, July 2025. Retrieved from https://icc-ccs.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/2025-Jan-Jun-IMB-Piracy-and-Armed-Robbery-Report-1.pdf

[2] Raj M. Desai, George E. Shambaugh, Why pirates attack: Geospatial evidence, Brookings, March 15, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-pirates-attack-geospatial-evidence/

[3] Jatin Dua, Piracy and Maritime Security in Africa, Oxford University Press, March 26 2019. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.829

[4] Safety4sea, IMB: 50% increase in piracy incidents in first six months of 2025, July 9 2025. Retrieved from https://safety4sea.com/imb-50-increase-in-piracy-incidents-in-first-six-months-of-2025/

[5] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

[6] Tristan McConnell, Interview with a pirate, Global Post, June 12 2009. Retrieved from https://theworld.org/stories/2017/03/10/interview-pirate

[7] Desai, Raj & Shambaugh, George. (2021). Measuring the global impact of destructive and illegal fishing on maritime piracy: A spatial analysis. PLOS ONE. 16. e0246835. 10.1371/journal.pone.0246835. Retrieved from https://www.piclub.or.jp/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/2024-Jan%EF%BC%8DJun-IMB-Piracy-and-Armed-Robbery-Report-1.pdf

[8] ICC, IMB Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Report, ICC-IMB, 2024. Retrieved from https://www.piclub.or.jp/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/2024-Jan%EF%BC%8DJun-IMB-Piracy-and-Armed-Robbery-Report-1.pdf

[9] Kaija Hurlburt, Conor Seyle, (2013) The Human Cost of Maritime Piracy 2012, ICC, Oceans beyond Piracy, One Earth Future. Retrieved from https://www.grip.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/human_cost_of_maritime_piracy_2012.pdf

[10] Dinakar Peri, INS Kolkata secures release of 17 crew of merchant vessel turned pirate vessel Ruen, 35 pirates surrender, The Hindu, March 16 2024. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/indian-navy-thwarts-attempt-of-somali-pirates-to-hijack-ships/article67957352.ece

[11] Robert Wright, Surge in maritime violence boosts demand for private security forces, Financial Times, April 21 2024. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/5175a8b4-41cc-4b60-913f-dc6f2f68307d

[12] ICC, IMB Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Report, ICC-IMB, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.icc-ccs.org/reports/2020_Annual_Piracy_Report.pdf

[13] ICC, IMB Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Report, ICC-IMB, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.icc-ccs.org/reports/2022%20Annual%20IMB%20Piracy%20and%20Armed%20Robbery%20Report.pdf

[14] ICC, IMB Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships Report, ICC-IMB, 2023. Retrieved from https://www.icc-ccs.org/reports/2023_Annual_IMB_Piracy_and_Armed_Robbery_Report_live.pdf

[15] Balogun, Wasiu A. (2021): “Why has the ‘black’ market in the Gulf of Guinea endure?”, Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs. Retrieved from https://www.grip.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/human_cost_of_maritime_piracy_2012.pdf

[16] ReCAAP, ISC Annual Report 2024, Information Sharing Centre, 2024. Retrieved from https://www.recaap.org/resources/ck/files/reports/annual/ReCAAP%20ISC%20Annual%20Report%202024.pdf

[17] “Venezuelan pirates – the new scourge of the Caribbean”. BBC News, January 28 2019. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-47003108

[18] “Guyanese pirates handed heavy jail sentences in Suriname”. Kaieteur News, November 26 2019. https://kaieteurnewsonline.com/2019/11/26/guyanese-pirates-handed-heavy-jail-sentences/

[19] Tominaga, Yasutaka. (2016). Exploring the economic motivation of maritime piracy. Defence and Peace Economics. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304029273_Exploring_the_economic_motivation_of_maritime_piracy

[20] Jonathan Saul, Emma Pinedo, Abdi Sheikh, Hijacked ship off Somalia fuels fears pirates back in Red Sea waters, Reuters, December 19 2023. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/hijacked-ship-off-somalia-fuels-fears-pirates-back-red-sea-waters-2023-12-19/

[21] Giulia Paravicini, Jonathan Saul, Abdiqani Hassan, Somali pirates return, adding to global shipping crisis, Reuters, March 21 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somali-pirates-return-adds-crisis-global-shipping-companies-2024-03-21/

[22] Tar, Osman A. (2021): The Routledge Handbook of Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency in Africa, Routledge – Taylor & Francis Group.

[23] International Maritime Organisation, Resolution A.1025(26), December 2 2009. Retrieved from : https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/security/pages/piracyarmedrobberydefault.aspx

[24] Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency, President Buhari Launches Deep Blue Project in Lagos. Retrieved from : https://nimasa.gov.ng/president-buhari-launches-deep-blue-project-in-lagos/

[25] European Union External Action, EU Maritime Security Factsheet: The Gulf of Guinea, January 25 2021. Retrieved from : https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-maritime-security-factsheet-gulf-guinea_en

[26] UNDOC, Final Independent Project Evaluation Support To West Africa Integrated Maritime Security (Swaims), December 2024. Retrieved from : https://www.unodc.org/documents/evaluation/Independent_Project_Evaluations/2024/IPE_SWAIMS_Final_Evaluation_Report.pdf

[27] Kiss, Amarilla. (2020). Maritime Piracy in the Modern Era in Latin America: Discrepancies in the Regulation. Acta Hispanica. 121-128. 10.14232/actahisp.2020.0.121-128.

[28] NATO, Counter-piracy operations (2008-2016), Retrieved from : https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_48815.htm

[29] European Union, Operation ATALANTA, EUTM Somalia and EUCAP Somalia : prolonged mandates for two supplemental years, European Union Council, December 23 2020. Retrieved from https://basedoc.diplomatie.gouv.fr/vues/Kiosque/FranceDiplomatie/kiosque.php?fichier=bafr2021-01-06.html#Chapitre5

[Cover image] Picture by Ian Simmonds (https://unsplash.com/fr/photos/navire-naviguant-sur-un-plan-deau-XrDbdmqsPdk). Licensed under Unsplash (https://unsplash.com/fr/).

Leave a comment