After the Cold War, between the 1990s and the 2010s, the world was dominated by the idea that global trade, liberal democracy, and the foundation of institutions such as NATO, the UN, EU or WTO could guarantee a self-regulating international order. Realpolitik seemed to have come to an end, at least in Western foreign policy [1].

But how can we define Realpolitik? Contrary to widespread belief, Realpolitik is not a synonym of “realism,” “realist,” or “raison d’état,” it has its own origins that often are misinterpreted [3]. This word first appeared in the treatise authored by a German liberal journalist, August Ludwig von Rochau, in 1853, titled “Grundsätze der Realpolitik, angewendet auf die staatlichen Zustände Deutschland” [3]. Writing in the aftermath of the failed liberal revolutions of 1848, Rocheau argued that noble values such as justice and democracy were not sufficient on their own to guide a nation, in fact he believed that only through practical, strategic engagement with the existing power, it is possible to achieve these ideals [3].

In Rochau’s words, Realpolitik:

“Does not move in a foggy future, but in the present’s field of vision, it does not consider its task to consist in the realisation of ideals, but in the attainment of concrete ends” [3].

Later, in 1915, Henry C. Emery, an American economist, discussed Realpolitik in his work “International journal of Ethics”. In this book, Realpolitik is defined as a political approach where a statesman is influenced only by existing circumstances and needs, contrasting with those who rely on doctrines or rhetoric [4]. Additionally, Emery stated that Realpolitik distinguishes between political realism, which focuses on the actual needs of the state at a given time, and political idealism, which is based on ethical or political ideals [4]. Each of these concepts can be exaggerated; realism may lead to materialistic aims, while idealism can result in impractical fantasies [4].

However, over time, the meaning of this term has been distorted. People started to confuse Realpolitik with Machtpolitik, for instance [3]. Machtpolitik, as the name suggests, is a political approach based on force and domination. This misunderstanding emerged mostly under the Bismarckian period when the concept of Realpolitik shifted from Rochau’s liberal pragmatism to a more power-centred approach [4].

Having outlined the meaning and origins of this ambiguous term, we can now ask: where does the thread linking Realpolitik to contemporary politics lie? Over the past two decades, the world’s balances have changed [1][5]. As stated earlier, the liberal politics of the post-Cold-War era no longer exist today. International relations scholars described the world as being at an inflection point [5]. In fact, the current global system is defined by multipolarity, with emerging powers reshaping economic, military, and technological dynamics. New powers such as China, India, and emerging ones such as Indonesia, Brazil, and Türkiye are asserting their influence, challenging the primacy of Western countries [5].

Focusing mainly on the case of Europe, one of the first signs that the EU needed to adjust its foreign policy came on 28 June 2016 [2]. On that day the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy for the European Union, from 2014 to 2019, Federica Mogherini, presented the Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy (EUGS) to the European Council [2]. This project represented a return to Realpolitik, but in a way that incorporated European characteristics. The EUGS acknowledged the limitations imposed by the EU’s capabilities and the complexities of the global environment. It aimed to navigate between isolationism and interventionism, promoting what was termed “principled pragmatism”, a political approach that evokes Realpolitik, but keeps intact EU ideals. The strategy identified five key priorities, including the security of the EU itself, along with its neighbourhood, addressing crises, establishing stable regional orders, and promoting effective global governance, with the main focus preserving Europe’s interests. It had as its main goal reducing fragility in neighbouring states rather than attempting to change their regimes [2].

The EUGS shows that as early as 2016, Europe recognised the need to adjust its foreign policy. However, the attempt had poor results, in fact the project was not entirely implemented. Meanwhile, the global system shifted from a unipolar one (with the US as the most influential power) to a multipolar system, where growing powers such as China, Russia, and India, and to a different extent, emerging actors like Türkiye, pursue their own, often divergent, interests [1]. The result is a world with new fluid alliances and opponents, not entirely different from the one Bismarck once navigated in 19th century Europe.

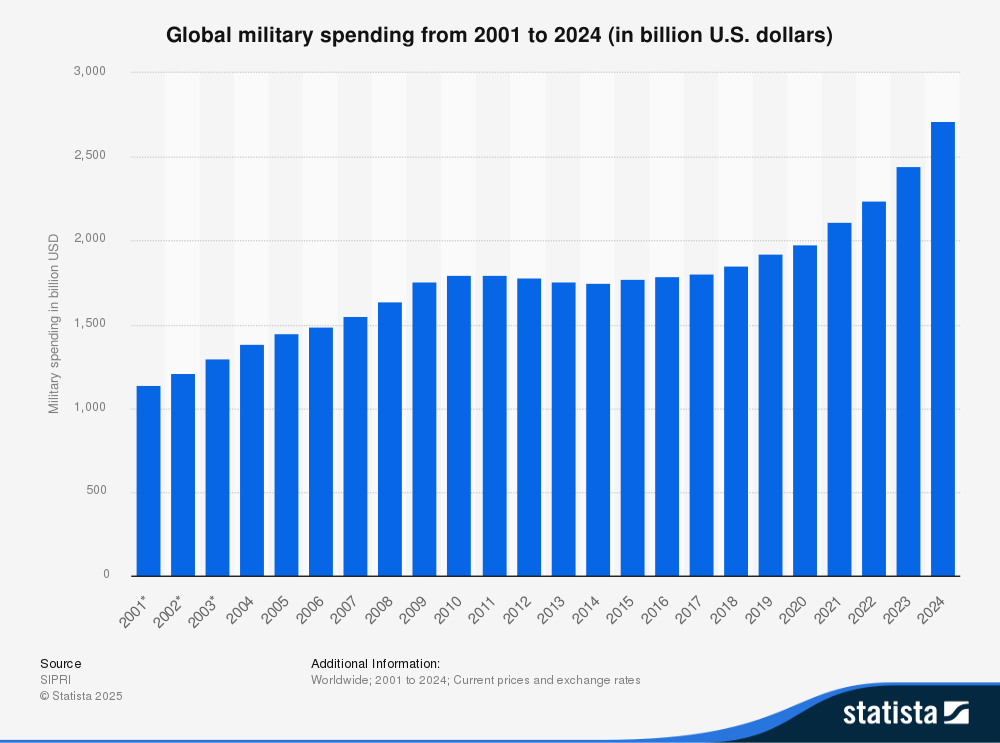

These shifts in strategies and behaviours of the most important states can be seen in multiple domains [5]. Military spending is on the rise, for example, nuclear disarmament efforts have stalled, and multilateral institutions such as the U.S play a diminished role. However, at the same time, economic independence is weaponised through trade wars and sanctions. Proxy conflicts and hybrid warfare illustrate how states today prioritise practical, interest-driven strategies over ideological alignment [5].

SIPRI. “Global Military Spending from 2001 to 2024 (in Billion U.S. Dollars).” Statista, Statista Inc., 28 Apr 2025, https://www.statista.com/statistics/264434/trend-of-global-military-spending/

In this context, global order no longer depends solely on ideals, but on the exercise of power, and the alignment of interests. History teaches us that the international system is fragile, dependent on numerous factors, that is why neglecting responsibility leads to instability, conflicts, and the rise of aggressive personalities. Realpolitik is not equal to cynicism, but recognises the existence of political interests, fluid alliances, and strategic calculation [6].

Edited by Jules Rouvreau.

References

[1] Institute for Economics and Peace. Geopolitical Influence and Peace: Tracking the Trends Shaping International Relations. Institute for Economics & Peace, 2025. Accessed 12 October 2025.

[2] Biscop, Sven. The EU Global Strategy: Realpolitik with European Characteristics. Egmont Institute, 2016. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep06638 . Accessed 12 October 2025.

[3] Schuett, Robert, and Miles Hollingworth, editors. Edinburgh Companion to Political Realism. Edinburgh University Press, 2018. https://books.google.it/books?id=tJBJEAAAQBAJ . Accessed 12 October 2025.

[4] Emery, Henry C. “What Is Realpolitik?” International Journal of Ethics, vol. 25, no. 4, 1915, pp. 448–68. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2376875. Accessed 12 October 2025.

[5] Cooper, Zack, et al. “An American Strategy for a Multipolar World • Stimson Center.” Stimson Center, 15 September 2025, https://www.stimson.org/2025/an-american-strategy-for-a-multipolar-world/ Accessed 12 October 2025.

[6] Stewart, Brian. “The Multipolarity Mirage: First Among Equals and the Illusions of Post-Unipolarity.” Quillette, 8 Sept. 2025, https://quillette.com/2025/09/08/the-multipolarity-mirage-first-among-equals-emma-ashford-review/. Accessed 12 October 2025.

[Cover image] Sebastian Voortman: https://www.pexels.com/it-it/foto/due-pezzi-degli-scacchi-d-argento-sulla-superficie-bianca-411207/. Due Pezzi Degli Scacchi D’argento Sulla Superficie Bianca. N.d. Retrieved from pexels.com.

Leave a comment