Oil defined geopolitical power in the 20th century as critical raw minerals and rare earth elements are defining the 21st. From the batteries that power electric vehicles to the components needed in wind turbines and fighter jets, modern economies depend on a handful of elements that are mined, refined, and controlled by only a few nations. Today, China’s dominance over the extraction and processing of these materials has opened a new geopolitical battleground, shaped less by ideology than by control over supply chains. As the United States and its allies scramble to secure alternative sources, global alliances are being reshaped, and a new era of strategic competition is emerging. The hunt for rare earths and critical minerals has become a national priority for governments seeking to secure technological, industrial and defence sovereignty.

REEs and CRMs – An Overview

Rare Earth Elements (REE) and Critical Raw Minerals (CRM) are becoming increasingly used acronyms in today’s news media. But what are they really? REEs are seventeen specific metallic elements. They are essential to more than 200 products with wide-ranging applications from high tech consumer goods all the way to the defence industry. This includes EVs, phones, semiconductors, and defence systems such as radars and sonars [1].

CRMs are on the other hand a much broader category. It includes REEs but also a wider array of materials significant to domestic economies, technology, security and development. Clean energy technologies rely heavily on CRMs — as do batteries and the technologies associated with REEs — illustrating just how essential these materials are to states and to their enduring power and security [2].

As stated on the EU’s official pages, CRMs are non-energy raw materials used in all industries in all stages of the supply chain. Technological progress and quality of life rely on the increased access to these materials. They are key drivers to develop and grow clean energy industries essential for the green transition [2].

China’s Stronghold On CRMs

The US has since the 1990s outsourced REE production and refining to China, where they are cheaper to mine and process. Japan, Russia, and the EU are also reliant on China to provide these materials, which explains why China today controls about 70 percent of production of REEs and over 90 percent of REE refining globally [3]. This means that China holds considerable leverage through export restrictions, creating national security threats to all importing nations.

EIPS promotion

Following the strategic decisions in China in the 1980s to expand its mining and processing industries, many western suppliers fell out of business — priced-out by highly competitive Chinese exports. Suppliers in China caused the market to oversaturate, pushing global market prices for REEs down sharply [4]. This enabled them to capture a large share of the market and begin operating the world’s largest known deposits of RREs.. Located in Inner Mongolia, the Bayan Obo mine is today the world’s largest REE deposit, vital to China’s security, power, and development. China, however, is far from the only country abundant in REEs and CRMs. Other states include Brazil, Canada, Greenland, Russia and India. Certain South American nations also hold the world’s largest deposits of lithium, vital to EVs. The Democratic Republic of Congo, DRC, has the world’s largest reserves of cobalt and coltan [5].

“Baiyun Obo Mine, Inner Mongolia, China” — NASA Earth Observatory (2006), Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

Mineral Dependency s a Geopolitical Tool

Thirty years ago, the global production mix of these materials looked significantly different. While China had picked up its own mining and refining industries and produced around 38 percent of REEs globally, the US was close behind at 33 percent. Other notable producers included Australia, Malaysia and India. However by 2011, China had absorbed the majority of global production , controlling over 90 percent of its processing [1].

This monopoly already deeply concerned China’s trade partners, with the ability to set prices, control sales, and limit exports. This fear materialised in 2010, after a maritime dispute between China and neighbouring Japan, one of its main trading partners. China momentarily suspended REE exports to Japan, causing immense economic distress to the innovative, tech industry Japan is known for. It signalled to the world that China was not afraid to leverage its monopoly as a geopolitical weapon [6].

In the aftermath, the prices of multiple elements skyrocketed, prompting the US, Japan and the EU to file a complaint with the World Trade Organisation (WTO). And although the WTO ruled against China in 2014, the damage had already been done. The episode ultimately underscored China’s leverage, revealing how little influence international bodies such as the WTO had in persuading Beijing to alter its behaviour [7]. This dynamic is not confined to Asia, however — it extends into the Arctic as well.

Greenland, a Case Study

Among the countries mentioned above, Greenland offers one of the clearest illustrations of how determined the United States is to secure independent access to CRMs and, by extension, REEs. The US proposals in 2019 and again in 2024 to purchase Greenland from Denmark — although seemingly eccentric and widely condemned— were almost certainly driven by deeper strategic calculations. Beneath its permafrost, Greenland possesses vast deposits of rare earth elements. Having failed to acquire the territory outright, US officials have since sought to persuade both Greenlandic and Danish leaders to restrict Chinese involvement on the island [8]. This highlights not only Washington’s desire to keep Beijing away from Arctic resource access, but also its ambition to secure such access for itself. From a strategic perspective, obtaining control over Greenland — with its location, sparse population, and abundance of natural resources — could potentially be one of the most consequential geopolitical moves the United States could make in the 21st century. Greenland, however, is not for sale.

During the same year as the US first tried to purchase Greenland, China and the US were facing trade war tensions. The US under President Trump imposed tariffs on products using Chinese goods, due to the trade imbalance issue, but faced backlash as China imposed similar tariffs on goods and export-restrictions affecting REEs as retaliation [9]. This showed the world that China may not be subject to external economic pressure.The same line of strategy has persisted, as China has launched new REE production facilities. Today, in the midst of the Trump administration’s aggressive trade war, China is issuing export permits, for instance in materials used in semiconductors. This spat may signal a more hostile future in resource trade [10].

Exploring US’s Options

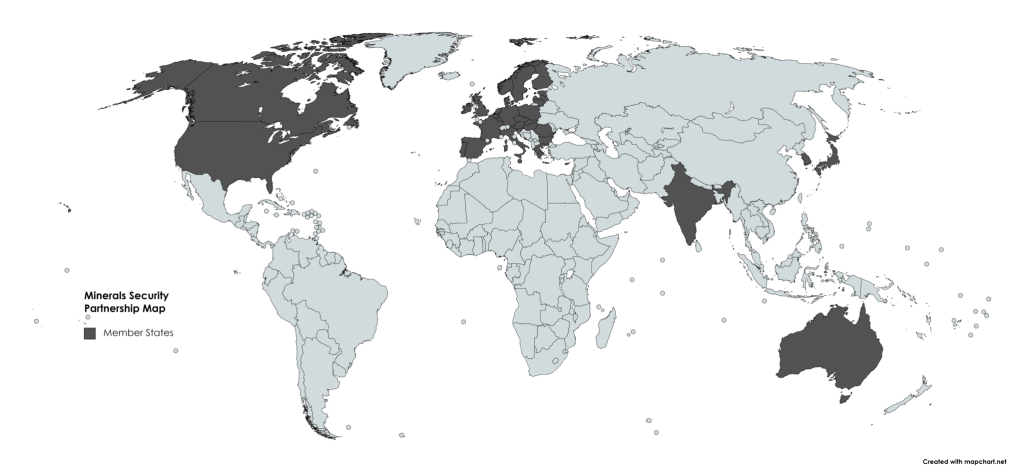

Hostility is forcing China-reliant countries to explore other ways to secure access to CRMs. The US has for instance launched the Mineral Security Partnership (MSP) with allies such as Australia, Japan, Canada, and the EU, with the aim to secure resources access. The MSP has funded mining projects in South America, partnered with African nations to pursue ethical mining and has expanded ties with Australian companies [11]. It nevertheless raises questions on whether these projects — even with further development — can ever measure up to Chinese output or ever cease to rely on it.

“Minerals Security Partnership member states” — U.S. Department of State (2024), Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Due to a lack of domestically available options, the US and the MSP are looking into REE recycling and substitutes. This however relies on heavy innovation and R&D from private entities in the industry. To promote material sourcing from the MSP nations, the US is providing economic incentives such as federal funding, grants and R&D funding [12].

Looking inward, the US is reopening old mines, such as the Mountain Pass mine in California, and a number of companies are also searching for REE deposits domestically [13]. However, refining facilities would need to be established, as the supply chain historically included shipping the raw ores to China to be refined there [14]. That illustrates how dependent the US is on China in order to secure resources and in turn, shows how much power the Chinese have over the US and the West at large.

Conclusion

As the world races toward clean energy and digital transformation, access to critical minerals has become the new measure of global power. The power held by oil-producing nations of the twentieth century now defines the mineral economies of the twenty-first. China’s foresight in building vast refining capacity decades ago has granted it a leverage that military power might struggle to equate. The US and its allies are only beginning to rebuild what they once outsourced, a process that will take years, perhaps decades, to mature.

This imbalance has revived an East–West divide reminiscent of the Cold War — not ideological, but material. Today’s geopolitics is shaped by protectionism, supply-chain politics, and environmental contradictions. Power now lies not only in armies or economies, but in the minerals that sustain them. Unless Western nations can innovate, cooperate, and reconcile sustainability with security, they risk a future contested not over ideas, but over seventeen metals buried in the ground.

Edited by Maxime Pierre.

References

NASA Earth Observatory (2006) Baiyun Obo Mine, Inner Mongolia, China [Image] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baiyunebo_ast_2006181.jpg (Accessed 2 November 2025).

U.S. Department of State (2024) Minerals Security Partnership Map [Image]. Available at:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Minerals_Security_Partnership_Map.png (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[1] American Geosciences Institute (n.d.) What are rare earth elements and why are they important? Available at: https://profession.americangeosciences.org/society/intersections/faq/what-are-rare-earth-elements-and-why-are-they-important/ (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[2] European Commission (n.d.) Critical raw materials. Available at: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/areas-specific-interest/critical-raw-materials_en (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[3] Park, Sulgiye, et al. “Reimagining US Rare Earth Production: Domestic Failures and the Decline of US Rare Earth Production Dominance – Lessons Learned and Recommendations.” Resources Policy, vol. 85, no. 0301-4207, 1 Aug. 2023, pp. 104022–104022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.104022. (Accessed 14 December 2025).

[4] “History and Future of Rare Earth Elements.” Science History Institute, 11 Oct. 2024, www.sciencehistory.org/education/classroom-activities/role-playing-games/case-of-rare-earth-elements/history-future. (Accessed 14 Dec. 2025).

[5] Council on Foreign Relations (2024) The U.S. critical minerals dilemma: what to know. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/article/us-critical-minerals-dilemma-what-know (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[6] Yang, F.W. (2023) China’s rare-earth resource nationalism: learning from Japan’s experiences. Global Asia, Vol. 17, No. 4. Available at: https://www.globalasia.org/v17no4/cover/chinas-rare-earth-resource-nationalism-learning-from-japans-experiences_florence-w-yang (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[7] East Asia Forum (2014) Does the WTO ruling against China on rare earths really matter? Available at: https://eastasiaforum.org/2014/10/30/does-the-wto-ruling-against-china-on-rare-earths-really-matter/ (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[8] Danish Institute for International Studies (2023) Chinese investments in Greenland raise U.S. concerns. Available at: https://www.diis.dk/en/research/chinese-investments-in-greenland-raise-us-concerns (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[9] Council on Foreign Relations (2023) The contentious U.S.–China trade relationship. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/contentious-us-china-trade-relationship (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[10] Reuters (2025) China’s rare earth export controls are good for Beijing, bad for business. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-rare-earth-export-controls-are-good-beijing-bad-business-2025-07-07/ (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[11] Hamilton, E. (2025) Critical minerals and the global energy transition. DECUR Essay Series, University of Texas at Austin, pp. 1–7. Available at: https://sites.utexas.edu/mineralstransition/files/2025/06/DECUR-Essay_Emma-Hamilton.pdf (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[12] U.S. Department of Energy (2025) Critical Minerals and Materials Program: Building Secure Supply Chains for America’s Energy Future. Slides 8–15 and 44. Available at: https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2025-01/critical-minerals-materials-program-january2025.pdf (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[13] Mining Technology (2023) Exploring U.S. efforts to find a secure supply of rare earth elements. Available at: https://www.mining-technology.com/analysis/exploring-us-efforts-to-find-a-secure-supply-of-rare-earth-elements/ (Accessed 2 November 2025).

[14] Center on Global Energy Policy, Columbia University (2024) MP Materials deal marks a significant shift in U.S. rare earths policy. Available at: https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/mp-materials-deal-marks-a-significant-shift-in-us-rare-earths-policy/ (Accessed 2 November 2025).[Cover image] “Mining Excavation On A Mountain”, n.d (https://www.pexels.com/photo/mining-excavation-on-a-mountain-2892618/) by Vlad Chetan (https://www.pexels.com/@chetanvlad/) licensed under Pexels.com.

Leave a comment