By the EIPS Team

President’s foreword — Justine Dukmedjan

“My dear friends all over the world,

Today we celebrate a special New Year with a momentous number: the Year Two Thousand.

As we move into a new Millennium, many of us have much to be thankful for. Most of the world is at peace. Most of us are better educated than our parents or grandparents, and can expect to live longer lives, with greater freedom and a wider range of choices.

A new century brings new hope, but can also bring new dangers – or old ones in a new and alarming form. Some of us fear seeing our jobs and our way of life destroyed by economic change. Others fear the spread of bigotry, violence or disease. Others still are more worried that human activities may be ruining the global environment on which our life depends.

No one knows for sure how serious each of these dangers will be. But one thing they have in common: they do not respect state frontiers.

Even the strongest state, acting alone, may be unable to protect its citizens against them.

More than ever before in human history, we share a common destiny. We can master it only if we face it together.”

Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, “Message for the New Millennium”, 31 December 1999.

Our beloved Editor-in-Chief, Maxime Pierre, had a great idea a few weeks ago: for the end of the year, our paper should publish a recap piece about some (all might be a little overzealous) of the most important events that happened worldwide in 2025. And I should do the foreword. One reflecting on the whole year. Not an ambitious nor time-consuming task at all.

Dear readers, you’ll be the judge of whether or not asking me to do the foreword was a sound judgment call. Maxime will happily answer any complaint, should you have any after reading the following words.

Upon researching material for that foreword, I stumbled upon the “Message for the New Millennium” addressed by Kofi Annan to the world on New Year’s Eve, in 1999. While racking my head trying to find an angle, I had gotten curious about the general atmosphere surrounding the passage to the new millennium, twenty-six years ago. After all, 2025 marked the end of the first quarter of the 21st Century. So, at its dawn, what were people hoping from that 21st Century? I was expecting unbridled optimism and expectations, manifested in exuberant parties — and apparently there was a lot of that. But Kofi Annan’s words struck me. “Don’t take the seeming general progress towards a free, peaceful world for granted”, he seemed to say, “but beware of the ever-looming ‘dangers’ that never truly leave us”. Annan offers a solution in the rest of his message: entrust your fate to the United Nations, surrender to this ideal of a communal, shared governance between countries — the United Nations will be your salvation.

I am not here to make an assessment of the successes and failures of the UN in our first quarter of a century — far more qualified people than me have done it, and will keep doing it l. My only goal here is to reflect on 2025. Which is why I find the first part of Annan’s message of particular interest. 25 years into the 21st century, and we are knee-deep in those “dangers” he warns us about. The “new dangers” as well as the “old ones”.

Russia is once again the West’s sworn enemy and the war in Ukraine fails to end.

Antisemitism, acting under the guise of mere antizionism, has reached heights the Nazis would applaud.

Genocide and ethnic massacres are a dime a dozen in Africa, while the rest of the world watches idly.

It is the golden age of violent drug cartels in Latin America — so much that they inspire other thugs all over the world, who try to import a bloody underworld of death and dependence in their own countries.

The Middle East seems on the verge of blowing up every day, depriving the populations there of a well-deserved right to finally live.

India and Pakistan went to war again. So did Cambodia and Thailand.

Terrorism of all kinds is still going strong worldwide, with deadly terrorist attacks on the regular: Syria, Bondi Beach, Kashmir… To name only a few.

The Iranian nuclear threat remains after US-Israeli strikes.

Zoonotic diseases are on the rise.

China is at Taiwan’s door.

Communitarianisms and extremisms of many natures and ideologies are surging all over.

The EU and the US, once brothers, are now at each other’s throat.

People keep slaughtering each other all over the world for no other reason than their religion.

Fake news and conspiracy theories are gaining a new platform under the Trump administration. Such as, for example, dangerously antiquated antivax theories, leading, amongst other things, to the worst measles outbreak in the US in decades.

Elected officials around the world are making fools of themselves and democracy by fighting like three-year-olds inside of their respective parliamentary institutions.

You’ve got it. The list of plagues that riddled 2025 could go on and on and on…

I’ll end that long yet non-exhaustive list by saying that, on top of all that, we are also standing, in deafening silence, on the grave of freedom of speech. The general climate today across the political chessboard can be summed up like this: if you don’t think like me, you need to be silenced. One way or another. Ask Charlie Kirk: whether or not you agreed with him does not matter. What matters is that in 2025, we should have evolved past literally shooting down someone we disagree with. What happened to peaceful debate and confrontations of ideas?

But maybe therein lies the problem? We have not evolved? In all those millennia, we have switched goals, ideologies, religions, theories, hatreds, desires, regimes… We have grown numbers. We have mastered and savaged the world. We have perfected our weapons, until they could literally kill us all. We have gained access to technologies that we could not dream of a few decades prior. But, in spite of all those changes, all those scientific, technological advancements, have we really evolved? In the sense of bettering ourselves, morally, ethically, metaphysically? Or have we just sharpened our fangs and claws to always redo what is, in fine, the same macabre dance that leaves legions dead or hurting, usually for no good reason?

It’s a shame, all this violence, all this war, all this hatred. Because it hides our true potential. A potential that does not lie in making the deadliest missile ever, or the most performing AI, but in uniting towards a common goal that benefits us all. Whether or not we agree with the United Nations as an institution, Annan’s not wrong in calling for unity. Together, we can move mountains: we’ve nearly completely defeated AIDS, found cures for once incurable diseases, gave broad access to education all over the world, stopped a deadly pandemic, stopped terror attacks based on shared intelligence… So why is world peace so unreachable? I mean, if we can successfully find ways to bend genetics to cure diseases or send rockets to space, why can’t we just pause for a minute and consider getting past war and petty quarrels once and for all? Imagine what we could do, how far we could go, if we did not waste time, blood, and energy killing and hurting each other. Maybe the sky would not even be the limit anymore. Maybe cancer would be cured. Maybe the El Dorado would not be the El Dorado anymore but just the world we live in.

I know it sounds silly. The wishful thinking of a naïve youngster. But I assure you it’s not.

We started this glorious year of 2025 at 89 seconds to midnight, according to the Doomsday Clock. 89 seconds to the ‘apocalypse’. How close do you think we’ll be to midnight in a few days, as 2026 begins? Closer, I think. Maybe even much, much closer.

I don’t know about you, but I’d rather not live through the apocalypse. You probably wouldn’t either. So, maybe it’s time we all wake up. We are as collectively responsible for those 89 seconds to midnight as we are responsible for resetting the clock. We have gold in our hands: each other. As naïve as it sounds, in spite of the bleak picture of 2025, I still believe in humanity. Yes, we have proved to be capable of the worst, over and over. But we have also proved that we are capable of greatness. Goodness. So, if I had to make one vow for 2026, it would be this: that for once, we all go past our violent, petty, selfish instincts and choose to do some good that benefits not just ourselves, but those around us.

At our small personal level first. Even if you can’t do much about the war in Ukraine, placing help and respect as cardinal values, collectively, might in itself be a game-changer. If we start respecting each other, if we are willing to lend a hand, even to someone we disagree with, then we can unite. This is our strength. This is our best card to play. Together, we can influence the decision-makers, the course of events itself. We can say ‘no’ more and be heard. No more violence. No more hatred. No more death. No more pain. No more suffering. Yes, it will be a long road to world peace and collective happiness. A very, very, very long and rough road. But it has to start somewhere, at some point. Maybe it’s time to start now. Before the clock reaches midnight, and it’s too late.

I might have wasted a wish for 2026. I might have wasted perfectly good ink. But I truly believe in us, and hope that 2026 is the year we seize destiny and start working towards peace, safety, and happiness, instead of turning against each other and passively brooding about the state of the world.

COP30 Climate Summit by Vanisha Hemrajani — Head of Conferences Paris campus

Currently pursuing MSc International Business and Diplomacy at ESCP Business School in Paris. Former employee of the French Embassy in India.

Let’s fast-forward to 2050, when future generations will watch the COP30 talks on digital platforms and question the inaction of global leaders to save their lives. Or perhaps these future generations will not even have the energy supplies to do so, since the OECD warns that the growing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events present major risks to energy security.

This year’s COP30, held in Belém, Brazil, carried symbolic weight, taking place near the Amazon rainforest — the very heart of our planet — where deforestation continues to erode the foundations of climate action. The setting was a reminder that the fight against climate change is not abstract; it is rooted in the survival of ecosystems that sustain life itself. Yet, despite the urgency, the conference ended with applause but little ambition.

It has been ten years since the Paris Agreement, when nations pledged to pursue efforts to limit global warming to 1.5°C. Today, the world remains on track for 2.8°C of warming if current policies persist. While this is an improvement compared with the 3.5–4°C trajectory estimated around the time the Paris Agreement was adopted, the question remains: is the glass half full or half empty?

Investment in clean energy has grown significantly, surpassing fossil fuel spending in many regions. Yet energy insecurity continues to rise, and the Paris Agreement’s roadmap has not translated into sufficient action. Vulnerable nations, who were once promised funding to adapt and transition, argue that they are still being denied the financial resources they desperately need. Without predictable financial support, their reliance on fossil fuels is likely to persist, undermining global progress.

COP is often described as the world’s family gathering: a place where all members sit at the same table to discuss the planet’s future. But at COP30, the family forgot to serve the main dish: fossil fuels. Despite more than 80 countries pushing for an exit plan, the issue was left off the menu entirely. To make matters worse, one of the most powerful members of the family — the United States — did not send any high-level officials, leaving a void in leadership for climate ambition. If there is a silver lining, it is that fossil fuels are now firmly part of the conversation — and COP28’s outcome was the first to explicitly call for “transitioning away from fossil fuels”, a step many hoped COP30 would build on. But conversation alone will not bend the curve of emissions.

Many civil society groups summed up COP30 in one word: disappointment. While nearly 200 countries continued discussions, the absence of high-level US participation cast a shadow. Colombia and other nations pushed hard for fossil fuel phase-outs, but the final text remained silent. Instead, the agreement focused on financial pledges: the COP concluded with a call to at least triple finance for adaptation by 2035. Oil-exporting nations such as Saudi Arabia resisted fossil fuel phase-outs, while EU delegates tried to put on a brave face. The result was an agreement without ambition — better than nothing, but far from enough.

COP30 ended with cheers, but the celebration masked a sobering reality. Fossil fuel exit plans, essential to reducing emissions, were excluded from the final text. Developing countries, which had demanded funding by 2030, saw the headline adaptation finance target set for 2035. The Amazon setting reminded the world of what is at stake, but the outcome showed how far we remain from the unity and ambition required to safeguard our shared planet.

US-China Tech Confrontation by Gustav Graner — Senior contributor

I am a 3rd year Bachelor student currently based in London, but originating from Uppsala, Sweden. In terms of international relations, I have a particular interest in the historical and economic aspects.

The US-China relationship has continued to take centre stage in 2025 geopolitics, with the development of Artificial Intelligence and its adjacent technologies at the forefront of this year’s diplomatic frontier. With an increasingly multi-polar world, both the American and Chinese administrations have emphasised the importance of AI innovation within their own borders, leading to huge investments in domestic technology, as well as efforts to prevent this development to be copied abroad.

At the start of the year, America was seen as winning the race with companies like OpenAI, Anthropic and Alphabet having already developed advanced closed-source models which competed for market share. At the same time, US-based Nvidia dominated the market for advanced Graphic Processing Units (GPUs), which are essential in improving and running Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT. In January however, the development and rise of DeepSeek’s latest LLM shook the industry. With a budget much smaller than US competitors, DeepSeek was able to use open-source coding to create an application which could compete at the highest level of AI. The race was on.

Almost a year later, it is safe to say that the race has no definitive winner. While the Trump administration, and its ‘AI tsar’ David Sacks, have pushed for deregulation and spurred investment into data centres from all major US companies, China’s own enterprises are not far behind. Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia, warned earlier in the year that they are “nanoseconds” behind the US in chipmaking. Whilst they have not been able to produce chips as advanced as the US yet — chips which are the bedrock of AI — they are closing the gap narrowly, setting the stage for increased tensions in 2026.

In relation to the race, earlier this year the US began, for the first time, to allow the sale of advanced Nvidia GPUs to Chinese companies, which is projected to start in early 2026. This move was made to promote growth of US companies, as sales to China will create increased flow of capital from China to the US, however it has been criticised for allowing China to access technology which help them in their pursuit of better AI. This balance between the national economy and the pursuit of better AI will likely shape the future of the technological race. With some warning that the US tech sector is entering bubble territory, many large scale companies already having taken much debt in order to finance further construction of AI infrastructure, and the US population suffering from the affordability crisis, difficult decisions will have to be made on how to develop AI in a way that populations can directly benefit from in the present.

Global Implications of Ukraine’s Drone Warfare by Maxime Pierre — Chief Editor

Holding a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in hospitality management, I was fortunate to work across multiple continents, broadening my cultural exposure and deepening my understanding of diverse perspectives. My raison d’être is earnest and transparent reporting, where truth-seeking is the ultimate goal rather than the pursuit of a flashy headline. If evidence goes against my assumptions and invalidates days of work, so be it — the next undertaking will yield even better results.

On November 22, mysterious drones were spotted near the Netherlands’ Volkel airbase, shutting down air traffic at its main airport for over two hours. This incident was one of many drone incursions, acts of sabotages and bomb threats witnessed across Europe, a considerable share of which trace back to Russia. “Hybrid warfare” is the term commonly used by defence analysts, explaining that Russia and other malign actors are purposely testing our responses to these threats — both physically through the EU’s reaction time to suppress them, and politically through EU unity and strategic response.

The Netherlands drone sightings come against the backdrop of other airspace violations: Berlin and Bremen airports briefly closed over the weekend of October 4 and 5. A month later, on November 4, drones greatly disturbed air traffic throughout Belgium. A day later, 20 kamikaze drones deliberately entered Polish airspace through western Ukraine — examples abound.

The asymmetric response to those repeated aerial threats were crudely summarised by Reinier van Lanschot, Dutch member of the European Parliament, after the sighting on November 23: “How many drones did it take to shut down European skies? About 5. How many drones are over Ukraine? About 500… every night. If we face that, we are not prepared at all. Ukraine learned the hard way how to defend itself against drones and they understand: you should not shoot down a cheap drone with a million-euro missile. Their technology is cutting edge, and Ukrainian instructors are in the EU right now training European soldiers. Putin exploits our weaknesses and depletes our air defence on his terms. We have let a war criminal drag us into a boxing match and made him the referee. But if we stop being afraid to act, we can respond on our terms. Protect our skies, build the ‘Drone Wall’, stop buying Russian gas, give up all the frozen assets and set up a no-fly zone in Western Ukraine. Colleagues, Ukraine is helping us, but we don’t say ‘thank you’ enough!”. He was not directly advocating for machine gun-mounted pickup trucks around critical infrastructure in the EU, as it is the case in Ukraine, but the solution evidently lies in low-cost interception methods.

This view that only a more forceful response will deter Putin is gaining traction across Europe. NATO chief and ex-Prime Minister of the Netherlands, Mark Rutte, declared in December — echoing previous statements — that “Russia is already escalating its covert campaign against our societies […] we must be prepared for the scale of war our grandparents or great-grandparents endured.” Those words would have been considered saber-rattling a few years ago, but are now merely reflecting the current geopolitical reality. To respond accordingly, the EU must greatly increase its investment in Ukraine and in its own defence. As the adage goes: “weakness is provocative”, hence the need to engage in the primitive dialogue the Kremlin seems to understand: peace through strength.

Shadow Fleet Resilience Despite Sanctions by Emile Beniflah — Head of Conferences Paris campus

I am a French-American master’s student in International Business and Diplomacy, and serve as Co-Head of Conferences for the International Politics Society in Paris. My interests focus on maritime trade, energy, and the Asia-Pacific region, where I spent a year studying and traveling.

At the time of writing, American forces have seized a second crude carrier off the coast of Venezuela, and imposed a blockade restricting most ships from entering and leaving Venezuela. At the same time, Ukrainian forces have attacked Russian oil tankers. These events mark a significant escalation in the way nations are combatting the so-called “Shadow Fleet.”

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) defines the Shadow Fleet as vessels engaged in illegal activity, used to bypass international sanctions and evade compliance. An estimated 17% of all in-service oil tankers fall under the Shadow Fleet category, with many more participating to some degree in the illicit trade of sanctioned energy (Domballe et al., 2025). Some of these ships trade openly in markets affected by sanctions. Others operate more discretely, engaging in ship-to-ship transfers. This process allows ships to launder illegal cargo, and makes it difficult to hold those complicit in such activities accountable.

This has long frustrated Western nations, which have used sanctions and economic measures to target key companies and actors in sanctioned states. While these measures have caused some economic harm and added complexity to exporting activities for sanctioned nations, they have also led to the emergence of a large and sophisticated black market. Russia, for instance, has built up a fleet of hundreds of Shadow Fleet vessels, which have been able to generate significant revenue. This has undermined Western efforts to reduce Russia’s primary source of income.

This year, however, there has been a different and more assertive approach to combatting Shadow Fleet activity.

First, the United States has put heavy economic and diplomatic pressure on India, including a 25% tariff rate increase, to limit its imports of Russian energy. While India continues to purchase Russian fossil fuels, there has been a reduction in imports from New Delhi. The United States has gone beyond simply enforcing sanctions and has actively used trade leverage to directly disrupt the Shadow Fleet trade.

Second, the Trump administration has escalated its actions significantly against Venezuelan energy exports. This month, U.S. forces seized two large crude carriers linked to the transport of Venezuelan oil and imposed a blockade severely limiting vessels entering and leaving Venezuelan ports.

Finally, Ukraine has, in recent months, attacked three Russian-owned tankers, damaging the vessels and extending its campaign against Russia’s energy infrastructure.

What these recent developments mark is a clear shift in how states enforce economic pressure. While sanctions were designed as a powerful way of coercion without the use of force, states are increasingly turning back to more traditional methods of power — using force and direct intervention to close the backdoors Russia, Iran, and Venezuela have relied on to continue trading.

Ukraine’s Long-Range Strikes Disabling Russian Refineries by William McAndrew – Head of Conferences Turin Campus

I am an English-American student currently studying for a degree in International Business Management at ESCP Business School. I serve as Head of Conferences at the ESCP International Politics Society, where I develop and host discussions with industry leaders and political figures to foster meaningful dialogue between students and professionals. I have a strong interest in foreign policy and energy security, and I explore issues such as strategic energy dependence, the implications of global supply-chain shifts, and the role of diplomatic engagement in strengthening national resilience.

On January 25, 2024, a major fire broke out at Rosneft’s Tuapse refinery on Russia’s Black Sea coast. Reuters reported Russian authorities claimed the blaze was extinguished, while a Ukrainian source separately told the outlet that Ukrainian drones had attacked the facility.

As a result of these attacks, the Rosneft refinery shut down until late April, underscoring how Ukraine’s drone strikes can lead to extended downtime in the Russian supply chain. The Tuapse outage mattered because it likely removed a chunk of Black Sea refining capacity for weeks, which can tighten the regional availability of refined products (especially diesel) even if Russia can reroute some crude and product flows. This shows how Ukraine is revolutionising the way war is fought, by attacking key Russian infrastructure, they are effectively crippling its ability to continue fighting with the same ferocity. The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) characterised the Tuapse strike as part of Ukraine’s expanding long-range drone effort against Russian energy infrastructure, linking these attacks to broader pressure on Russia’s war-sustaining economy. Repeated hits on refineries and fuel sites also force Russia to disperse air defenses and rear-area security, creating tradeoffs between protecting critical economic nodes and sustaining front-line coverage.

On March 13, 2024, Reuters reported a second consecutive night of Ukrainian drone attacks that hit major Russian oil infrastructure, including a fire at Rosneft’s Ryazan refinery, following damage the prior day to Lukoil’s NORSI (Nizhny Novgorod/Kstovo) refinery, based on Russian officials’ statements and reporting from the scene.

The fire at Russia’s seventh largest oil refinery, Rosneft’s Ryazan refinery marked a major blow to Russia’s oil production and caused a 2% increase in oil prices following negative supply speculation. Ukraine’s sustained attacks aimed at Russian oil infrastructure is a key part of a larger plan to defend itself by crippling Russia’s ability to fund its war. In an April 2024 International Energy Agency (IEA) report, the Ukrainian drone attacks are estimated to have targeted over 2 million barrels per day worth of crude oil processing capacity (around 2.5% of global processing capability). This led to an over 500k bp/d drop in crude processing capability in the first quarter of 2025. These March refinery strikes are part of a sustained campaign to pressure Russia’s war economy and complicate rear-area security.

On April 27, 2024, Reuters reported that Ukrainian drones struck the Ilsky and Slavyansk oil refineries in Russia’s Krasnodar region, citing a Ukrainian intelligence source (SBU) and reporting that fires broke out at the facilities.

While not officially confirmed by Russian officials, using NASA’s FIRM application that shows irregular heat signatures around the world there are two distinct marks near Krasnodar and Slavyansk.

From a market perspective, the significance of the Krasnodar strikes is less about a single day’s flames and more about compounding downtime risk across multiple facilities: the IEA has repeatedly cautioned that refinery disruptions can translate into tighter availability of refined products depending on repair timelines and Russia’s ability to offset losses elsewhere.

Industry analysts put a rough scale on the cumulative pressure: S&P Global Commodity Insights assessed in May 2024 that the gross Russian refining capacity potentially affected by drone strikes was nearing 1 million b/d, alongside indications of weaker Russian product exports in April based on tanker tracking.

The April 27 refinery attacks look less like a one-off disruption and more like a sustained attempt to pressure Russia’s war-supporting “rear” by forcing expensive defense-and-repair tradeoffs, exactly the kind of long-range strike campaign ISW has described as part of Ukraine’s evolving, remote deep-strike approach.

The Insider documents 24 strikes on oil-and-gas infrastructure targets in 2024, followed by at least 18 successful attacks in just January–March 2025. Whether or not any single hit proves decisive, the shift from dozens per year to near-monthly suggests a campaign designed to compound effects over time, stretching air defenses, prolonging downtime through repeat targeting, and steadily raising the cost of keeping Russia’s fuel system (and the war effort it supports) running.

US Strategic Repositioning After The 2024 Election by Maria Antonietta Fiocchi — Contributor

I am a first-year Business & Management student at ESCP Business School. My interests are mainly related to academic disciplines such as finance, politics, and history. However, I am also drawn to philosophical pieces. Through a multidisciplinary education I aim to read and analyse the complex world we live in.

The new Trump administration, inaugurated after his election on November 5, 2024, is not only defined by the reintroduction of tariffs, sanctions, and the everlasting technological war against China; it is something different, more complex, a shift in American politics that has inevitably influenced the whole world. His strategic choices can be summarised in a few key points. After his election, there has been a shift from post-Cold War ideals that supported liberalism, free trade, and belief in the power of institutions like NATO. Instead, the new administration has pivoted, and now its main focus is a political approach, made of a mixture of nationalism, populism, and industrialism, named Trumpism. In practice, this approach translates into a different set of strategic actions.

Firstly, the introduction of tariffs on imports from countries like China, Canada, and Mexico, this is followed by the protection of borders, mainly the infamous wall between the South of the USA and Mexico. Additionally, the core concepts on which the new administration is based are described in the NSS (National Security Strategy), a document released by the White House that has the aim to explain the new administration policies of the new president in office]. The 2025 NSS has as core principles the “Balance of Power” and “Peace Through Strength”, points firmly protected by the US government: America must be first, and any country that threatens US’ interests becomes a problem, solved through cooperation with different states that share the US’ vision. A clear example of Trump’s political approach translated into action is US policy towards Venezuela. The White House has labeled the Venezuelan government, under the President Nicolás Maduro, as a threat against the American values, and interests, mainly of political, economic and strategic nature. In fact, Venezuela is an unstable country from a political point of view, and it is aligned with States like Russia, China, Iran, and Cuba, that are rivals of the United States. Yet, Venezuela is still a relevant country for Trump because of its substantial oil reserves. The American response to this situation has focused on sanctions, and coordinating actions with other allied countries rather than direct military intervention.

Overall, this new shift is remarkable for global relations between the major states. However, the Venezuelan case in particular shows a paradox in Trump’s political approach. In fact, even though isolationism is the center of the president’s politics, it is applied only when America’s interests are not involved, on the other hand, since the US is still one of the global superpowers, intervening, like it happened in Venezuela, is still fundamental, and unavoidable.

EIPS promotion

Collapse of Haiti’s Political System & Foreign Intervention by Jules Rouvreau — Editor

Student at ESCP Europe in the MSc in international business and diplomacy after completing a master in Applied Geo-economics in Science Po Bordeaux, I specialise in topics related to Space and Maritime economy.

Haiti didn’t “collapse” in 2025 so much as run out of a usable state. The transition authorities in the capital, Port-au-Prince, kept promising a path back to elections, but armed groups kept redrawing the map, one neighborhood, one highway, one port gate at a time — 90% of the city is now controlled by gangs. By mid-year, the UN was reporting 2,680 people killed between January and May alone, including children, with displacement hitting record levels as gangs pushed outward and residents fled in waves.

The political center of gravity was supposed to be the transition roadmap. CARICOM, acting as the region’s main diplomatic broker, repeatedly tied the transition to an election timetable that, at least on paper, would restore constitutional legitimacy. But 2025 exposed the trap: Haiti needs elections to regain authority, yet authority is what you need to hold elections. When large parts of the capital and key transport corridors are contested, voter registration becomes risky, campaigning becomes coercible, and turnout becomes a measure of fear as much as preference.

What made 2025 different was the speed at which security realities overtook political plans. A late-March attack in Mirebalais, where assailants seized a prison and freed hundreds, signaled that gang power was no longer a Port-au-Prince story alone. Meanwhile, metrics are more akin to the ones found in Sudan or D.R.C., countries devoid of a functioning state, with massive movement of population, instead of ones found in states going through a simple crisis. IOM’s displacement tracking reported nearly 1.3 million internally displaced by June, then more than 1.4 million by October, the highest recorded in Haiti. As the year wore on, foreign intervention shifted from uneasy stopgap to institutional redesign. The Kenya-led Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission, never a full UN peacekeeping operation, was widely viewed as outmatched by the scale of armed control and the pace of gang expansion. A US Congressional Research Service brief noted the UN Secretary-General’s assessment that a classic UN peacekeeping mission was not feasible under prevailing conditions, underscoring how the international system itself was searching for a workable model.

In September, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2793, authorising the MSS to transition into a “Gang Suppression Force” (GSF) backed by a new UN Support Office in Haiti (UNSOH). Reuters described the vote as an attempt to field a bigger, more muscular force amid catastrophic displacement and sweeping gang influence, while noting concerns among some Council members about clarity, resourcing, and precedent. A month later, Resolution 2794 renewed and adjusted the sanctions regime, signaling a parallel strategy: squeeze the financiers and facilitators as well as the gunmen. By December, Reuters reported US claims that up to 7,500 personnel had been pledged for the new configuration, ambitious on paper, and a reminder that Haiti’s security still depends on voluntary foreign capacity. France, also criticised for its meagre contribution to the GSF, announced a partnership with Haitian police on December 26, 2025, aimed at reinforcing the local forces against gang violence.

But 2025 also showed the limits of “more force” as a political answer. When Médecins Sans Frontières shut a major emergency center in Port-au-Prince, it wasn’t only a health story, it was a warning flare about the shrinking space for civilian life and neutral aid. The headline from 2025 is brutal in its simplicity: Haiti’s politics didn’t fail because nobody had a plan; they failed because nobody, inside the system, could enforce one. The international community responded by retooling intervention, betting that a harder security footprint plus sanctions could create breathing room for a political reset. Whether that bet buys a real election in 2026, or just a new phase of managed emergency, depends on something foreign missions have rarely been able to manufacture: a Haitian political compact strong enough to outlast the gunmen.

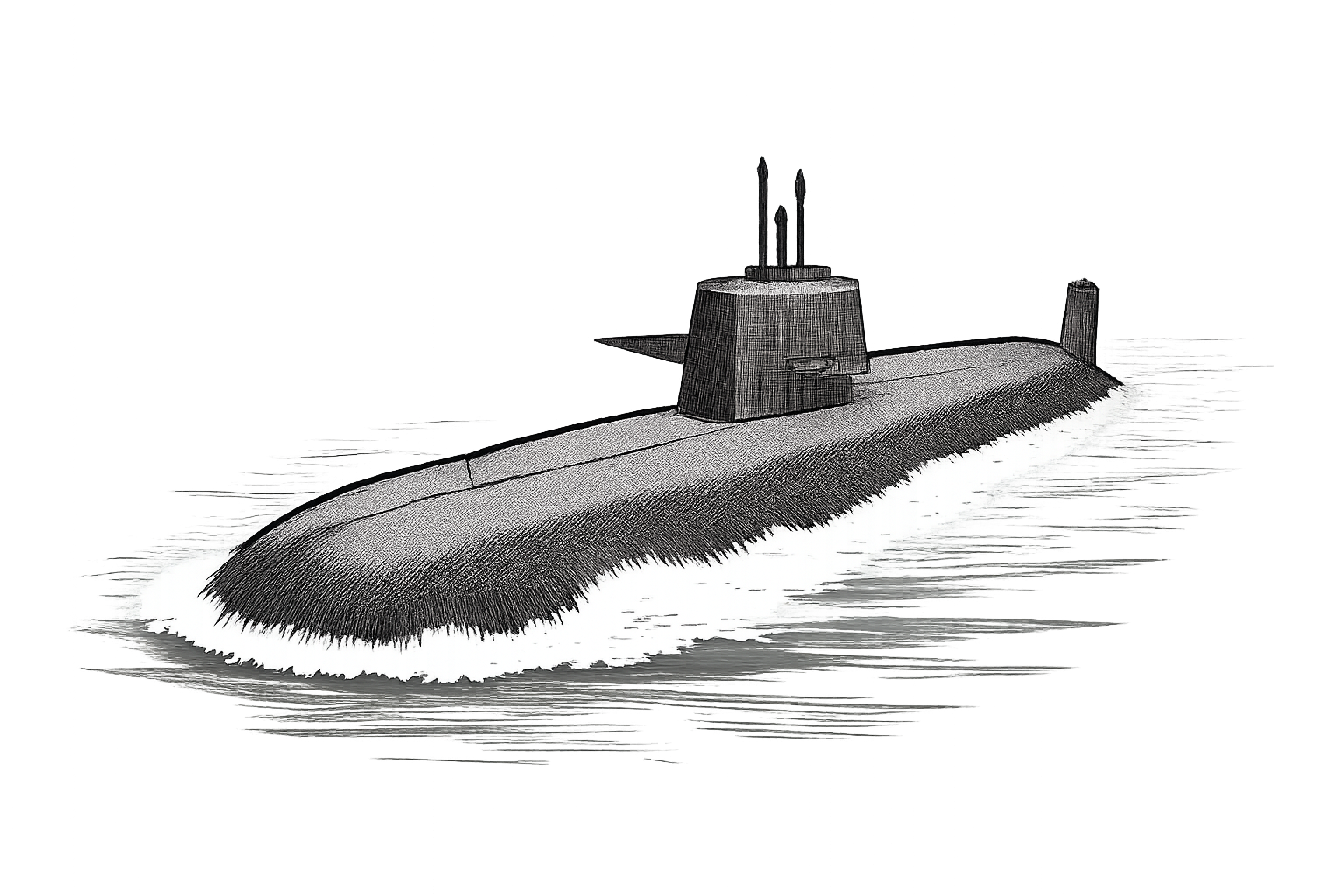

AUKUS Expansion & Indo-Pacific Security by Oriane Beveraggi — Editor

I’m a 21-year-old student from Corsica, currently completing my first year of the Master in Management at ESCP. I’m an artist at heart, I sing, dance, invent, and write, constantly exploring new ways to express ideas and emotions. Through my articles, I try to share my interest in current affairs and geopolitics, paired with a genuine love for writing and communicating with others. Above all, I write to connect, to transmit, and to share what moves me with clarity and enthusiasm.

Few issues capture the strategic uncertainty of a second Trump administration as clearly as the AUKUS defense pact. After Australia abandoned a previous defence deal with France in favour of one with the United States and the UK, they suddenly found themselves in a precarious position when President Trump called the agreement into question.

On June 11: The Pentagon launched a review of the 2021 AUKUS nuclear submarine deal, led by Elbridge Colby, throwing the security pact into doubt. The review examined whether the US should abandon the project amid concerns that selling submarines abroad could undermine US security as the navy struggles to produce more domestic submarines while facing rising threats from Beijing.

Critics suggested the AUKUS review aimed to force Australia to spend more on its own defence. The article noted that the US navy was trying to boost production to over two Virginia-class submarines per year by 2028, but production since 2022 had not exceeded 1.2 submarines per year. Several sources described the review as a “negotiating tactic” to get Australia to boost defence spending.

On June 20: Japan cancelled high-level defence talks with the US after Washington increased demands for more defence spending.

On July 13: The Trump administration pressed allies including Australia and Japan for commitments about what they would do in the event of a conflict over Taiwan. Australia’s defence industry minister refused to commit troops in advance, saying such decisions “will be made by the government of the day.”

On August 5: Australia selected Mitsubishi Heavy Industries to build up to 11 frigates worth $6.5bn, marking Japan’s first warship export deal. The order was part of Australia’s major defence overhaul alongside the AUKUS agreement.

On October 2: Australia undertook its most ambitious military overhaul since the Second World War to meet the China threat. Defence spending was forecast to rise to 2.25% of GDP by 2028 and potentially 3% within a decade as AUKUS and other expenditures came online, with the submarine deal estimated to cost between $178bn-$244bn by 2050.

On October 21: Trump offered strong public support for AUKUS, telling reporters the deal was “moving along very rapidly, very well” and they were going “full steam ahead.” His comments eased concerns about the Pentagon review.

In December: Following the conclusion of the US review, UK Defence Secretary John Healey declared Britain was going “all in” on AUKUS, backed by £6bn (around $8bn) of submarine infrastructure investment. US Secretary of State Marco Rubio confirmed Trump’s comment of October 21.

Iran Nuclear Negotiations by Félix Dubé — Editor

I am Félix Dubé, a 2nd year Bachelor in Management student at ESCP Madrid. And a Writer and Editor for ESCP International Politics Society. I really enjoyed reading novels and I am also a climber.

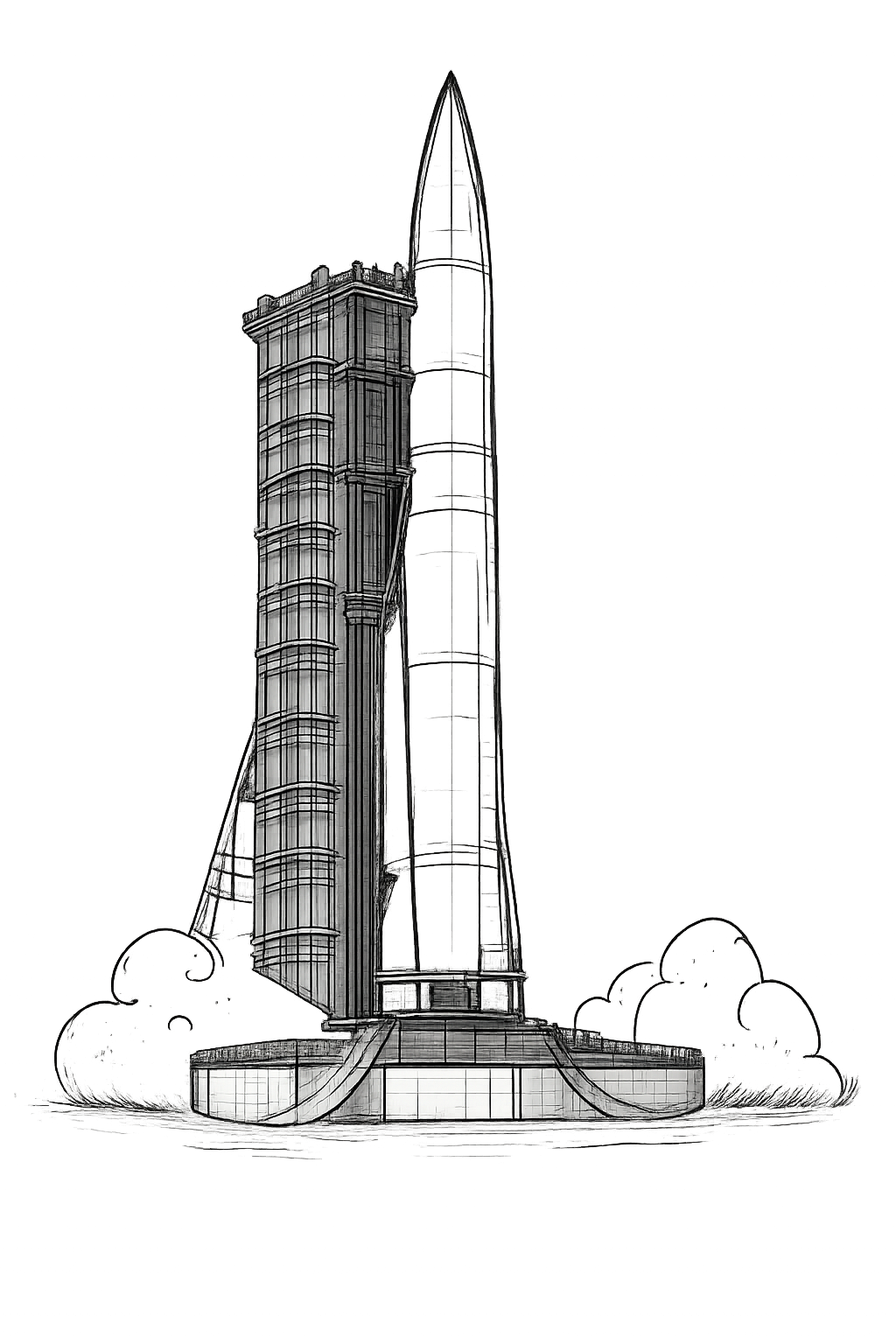

On October 18 2025, Iran terminated the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA): the day of the termination, Tehran declared that it was no longer bound by the 2015 nuclear agreement. This agreement had exchanged restrictions on Iran’s nuclear programme for the easing of Western economic sanctions on the country.

This announcement was not a sudden break, but the culmination of a negotiation process that had been crumbling for years. Indeed, the JCPOA could only work as long as both sides respected their part of the bargain: Iran agreed to strict limits and inspections on its nuclear programme, and in exchange, economic pressure from the West was eased. But when the United States under the first Trump administration left the agreement in 2018 and reinstated sanctions, Tehran gradually resumed its nuclear activities, partly with the aim of rebuilding leverage for future negotiations. In fact, since the US withdrawal, Iran has been enriching uranium to high levels (60% and above), approaching the military threshold of 90%. A technical assessment carried out in 2022 clearly explained that while Iran already has a large quantity of highly enriched uranium and sufficient centrifuge capacity, the time needed to produce weapons-grade material could be significantly reduced if it decided to do so.

This fear, whether or not Iran intends to build a nuclear weapon, is what makes the negotiations so urgent. However, by 2025, Europe’s attempts to revive the agreement were already shaken. And when Israeli-American strikes targeted Iran’s nuclear programme in June 2025, any hopes of reviving an agreement were shattered. Indeed, The Guardian reported that following the 12-day war, the Iranian parliament passed a bill refusing cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and that as a result, Britain, France and Germany triggered the JCPOA’s ‘snapback’ mechanism, reinstating UN sanctions against Iran that had been lifted under the agreement.

This perfectly reflects the failure of the Iranian nuclear negotiations, with sanctions returning in force as the main means of coercing Iran into negotiating — and Iran responding by declaring that the agreement itself was over.

Yet despite all this, in mid-November, Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi said Tehran could potentially resume nuclear negotiations with Washington, but only if it was treated with ‘dignity and respect’ — a way of saying that Iran will not negotiate if it feels threatened or humiliated, especially after being bombed during the negotiations. He also highlighted the fundamental issue that has repeatedly blocked agreements: Iran insists that it will not give up domestic enrichment, while the US has often wanted precisely that. Iranian officials even described an idea that had almost come to fruition in previous negotiations — a nuclear enrichment consortium based in Iran with outside participation — but this agreement, according to Iran, failed because of political ‘saboteurs’ in Washington.

As a result, the stakes involved in these potential future negotiations are extremely high, given the already fragile stability of the Middle East region. This is particularly true following the statement made by Israel’s Mossad Chief over Iran’s Nuclear Ambitions: ‘The idea of continuing to develop a nuclear bomb still beats in their hearts. We bear responsibility to ensure that the nuclear project, which has been gravely damaged, in close cooperation with the Americans, will never be activated’. From this fact, the UN and the Western diplomacy definitely has an important role to play in future negotiations in order to avoid an escalation over a potential nuclear conflict.

Sudan Civil War Escalation by Adrian Kai Fraile Itagaki — Contributor

Spanish and Japanese, and born in the Canary Islands, I enormously enjoy writing about everything related to economics, business and current affairs — blending cross-border insights with a twist of humor and a touch of cosmopolitan optimism.

2025 comes to an end, and it continues — three years on. Sudan has seen 12 million people flee their homes, around 4 million have left the country and more than 150,000 have died in the conflict. Statistics about the millions of displaced, the killings, sexual violence, humanitarian catastrophe and famine still cannot capture the individual tragedies of the Sudanese people.

In April 2023, fighting between SAF (Sudanese Armed Forces) and RSF (Rapid Support Forces) broke out. Under long-serving president Omar al-Bashir, who came to power in a coup in 1989 and was ousted in 2019 following pro-democratic protests, both SAF and RSF were part of the same security system. Together, they arrived to power in late 2021 but its leaders, General Al-Burhan (SAF) and Hemedti (RSF), fell into disagreements, plunging the country into a deadly civil war.

2025 has been marked by two military victories in two different cities. The first one back in May, when the SAF regained full control of the capital, Khartoum. This meant recapturing the main airport and government buildings, crucial for re-establishing control over the state’s institutions. The second happened in October in the city of el-Fasher, this time by the RSF. The paramilitary group consolidated its control over the Darfur region, in western Sudan. The RSF descends from militias responsible for the first Darfur genocide 20 years ago. The siege and subsequent fall of el-Fasher could therefore lead to another frightening escalation, with atrocities already committed on the civilian population.

The war’s longevity is sustained by funding streams — most notably Sudan’s illicit gold trade – which bankrolls both sides and enables the continued purchase of advanced weaponry; curbing these revenues could prove one of the most effective paths towards de-escalation.

The global reach is clear. The SAF relies on countries like Turkey, Iran and Egypt. And the UAE backs the RSF, arming them with drones. As unsuccessful peace talks took place in London, Washington and Geneva this year, a ceasefire backed by Trump — keen on winning the Peace Nobel Prize — emerged as one of the hopes for putting an end to the hostilities in 2026.

Edited by Felix Dubé, Oriane Beveraggi & Maxime Pierre.

References

President’s Foreword:

United Nations press release

United Nations. (1999, December 31). Message for the New Millennium (Press Release SG/2480). United Nations Information Service. Retrieved from https://unis.unvienna.org/unis/en/pressrels/1999/sg2480.html

Newspaper article — Times Square New Year’s Eve

McFadden, R. D. (2000, January 1). 1-1-00: From Bali to Broadway — a glittering party for Times Square. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2000/01/01/nyregion/1-1-00-from-bali-to-broadway-a-glittering-party-for-times-square.html

Non-governmental organization — Amnesty International

Amnesty International. (n.d.). Freedom of expression. Retrieved [insert retrieval date if required] from https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/freedom-of-expression/

Financial Times article

Hook, L. (2025, August 18). The inexorable rise of Latin America’s drug cartels. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/dc6b17fc-ba19-47b7-8a54-a7216356bf47 Financial Times

French Ministry of Foreign Affairs press release

Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (France). (2025, December 15). Syria – Terrorist attack on U.S. personnel (December 15, 2025). Retrieved from https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/syria/news/2025/article/syria-terrorist-attack-on-u-s-personnel-december-15-2025 France Diplomacy

Al Jazeera news article

Al Jazeera. (2025, January 29). Doomsday Clock is now 89 seconds to midnight, what does that mean?. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/1/29/doomsday-clock-is-now-89-seconds-to-midnight-what-does-that-mean Al Jazeera

Ukraine’s long-range strikes disabling Russian refineries:

Institute for the Study of War. (2025, April 27). Russian offensive campaign assessment. https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-april-27-2025

Institute for the Study of War. (2025, August 25). Russian offensive campaign assessment. https://understandingwar.org/research/russia-ukraine/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment_25-8/

International Energy Agency. (2024, April 12). Oil market report. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/3dbcfed3-7320-41a6-8339-85e016421536/-12APR2024_OilMarketReport.pdf

Reuters. (2024, March 13). Ukraine launches drone attacks on Russia for second night in a row, officials say. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraine-launches-drone-attacks-russia-second-night-row-officials-say-2024-03-13/

Reuters. (2024, April 27). Ukraine drones target two refineries, airfield in Russia’s Krasnodar region – Kyiv. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraine-drones-target-two-refineries-airfield-russias-krasnodar-region-kyiv-2024-04-27/

Reuters. (2024, May 17). Russia’s Tuapse oil refinery halted after Ukrainian drone attack, sources say. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-tuapse-oil-refinery-halted-after-ukrainian-drone-attack-sources-say-2024-05-17/

S&P Global. (2024, May). Russian refinery damage escalates after latest Ukrainian drone strike. https://www.spglobal.com/energy/en/news-research/latest-news/crude-oil/052024-russian-refinery-damage-escalates-after-latest-ukrainian-drone-strike

The Insider. (Nov 2025). [Refineries in the crosshairs: Ukraine’s “deep strike” strategy threatens major fuel shortages in Russia by 2026]. https://theins.ru/en/politics/286463

Implications of Drone warfare in war in Ukraine:

Al Jazeera. (2025, November 22). Air traffic suspended at Netherlands airport after drone sightings. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/11/22/air-traffic-suspended-at-netherlands-airport-after-drone-sightings Al Jazeera

Fenbert, A. (2025, November 22). Netherlands opens fire on suspicious drones near air base housing US nuclear weapons. The Kyiv Independent. https://kyivindependent.com/netherlands-opens-fire-on-suspicious-drones-near-air-base-housing-us-nuclear-weapons/ The Kyiv Independent

Instagram. (n.d.). Instagram reel. Retrieved [Month Day, Year], from https://www.instagram.com/reel/DRZ4iktDJ0j/

BBC News. (n.d.). Article title unknown. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn81x8py3j5o

ABC News. (n.d.). Article title unknown. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/WNT/story?id=130001&page=1

Shadow fleet resilience despite sanctions:

Domballe, J., McKinney, B., Nastali, I., Lin, M., & Koldova, A. (2025). Maritime shadow fleet: Formation, operation and continuing risk for sanctions compliance teams in 2025. https://www.spglobal.com/market-intelligence/en/news-insights/research/maritime-shadow-fleet-formation-operation-and-continuing-risk-for-sanctions-compliance-teams-2025

Rodriguez-Diaz, E., Alcaide, J. I., & Endrina, N. (2025). Shadow Fleets: A Growing Challenge in Global Maritime Commerce. Applied Sciences, 15(12), 6424. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15126424

Soldatov, A., & Borogan, I. (2025, November 25). Moscow’s offshore menace: How the shadow fleet enables Russia’s hybrid warfare in Europe. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/moscows-offshore-menace

Smialek, J. (2025, September 20). How Russia’s sanctions evasion could create lasting costs. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/20/world/europe/russia-shadow-fleet-oil-sanctions-ukraine-war.html

Smyth, J. (2025, December 21). US coastguard boards tanker carrying Venezuelan oil in Caribbean. Financial Times.

https://www.ft.com/content/fe6ff11a-52e7-4fb4-bd85-925b7d961c1b

US strategic repositioning after the 2024 election:

Bergamo, Mónica, and Celso Amorim. “Donald Trump’s Foreign Policy: A View from the Global South.”

Gate Center, 8 May 2025, https://gatecenter.org/en/donald-trumps-foreign-policy-a-view-from-the-global-south/ Accessed 7 December 2025.

“Could NATO survive a second Trump administration? | Brookings.” Brookings Institution, 25 June 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/could-nato-survive-a-second-trump-administration/ Accessed 7 December 2025.

“National Security Strategy.” The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/2025-National-Security-Strategy.pdf Accessed 7 December 2025.

“Trump casts doubt on willingness to defend Nato allies ‘if they don’t pay.’” The Guardian, 6 March 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/mar/07/donald-trump-nato-alliance-us-security-support Accessed 7 December 2025.

Watson, Jim, and Diana Roy. “Unpacking a Trump Twist of the National Security Strategy.” Council on Foreign Relations, 6 December 2025, https://www.cfr.org/expert-brief/unpacking-trump-twist-national-security-strategy Accessed 7 December 2025.

“Understanding Trumpism: Nationalism, Populism, and Industrialism.” Baron Public Affairs, https://www.baronpa.com/library/understanding-trumpism-nationalism-populism-and-industrialism

“White House Releases 2025 National Security Strategy | Brownstein.” Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, 9 December 2025, https://www.bhfs.com/insight/white-house-releases-2025-national-security-strategy

“Two US policy options for Venezuela: Shaping reform vs. ‘maximum pressure’ toward regime collapse.” Atlantic Council, 10 July 2025, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/two-us-policy-options-for-venezuela/?

Collapse of Haiti’s political system & foreign intervention

OHCHR. Haiti: UN Human Rights Chief alarmed by widening violence as gangs expand reach. 13 June 2025. Retreived from https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2025/06/haiti-un-human-rights-chief-alarmed-widening-violence-gangs-expand-reach

Evens Sanon, Danica Coto. Gangs strike in Haiti’s heartland as hundreds flee under heavy gunfire. AP News. 31 March 2025. Retreived from https://apnews.com/article/central-haiti-gangs-attack-mirebalais-saut-deau-8d93113d77c7ee5c7b505368f99bcef9

International Organization for Migration (IOM). Displacement in Haiti Reaches Record High as 1.4 Million People Flee Violence. 15 October 2025. Retreived from https://www.iom.int/news/displacement-haiti-reaches-record-high-14-million-people-flee-violence

Michelle Nichols, UN Security Council approves bigger force in Haiti to tackle gangs. Reuters. 30 September 2025. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/un-security-council-approves-bigger-force-haiti-tackle-gangs-2025-09-30

Congressional Research Service. Haiti in Crisis: Developments Related to the Multinational Security Support Mission. 3 June 2025. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/IN/PDF/IN12331/IN12331.12.pdf

Security Coucil Report. S/RES/2793. UN Documents. 30 September 2025. Retrieved from https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/un-documents/document/s-res-2793.php

Reuters. Rubio: US has pledges of up to 7,500 security personnel for Haiti. 19 December 2025. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/rubio-us-has-pledges-up-7500-security-personnel-haiti-2025-12-19

Jacqueline Charles. Haiti’s beleaguered police, army get elite French training as gang crisis deepens. Miami Herald. 26 December 2025. Retrieved from https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/haiti/article313951667.html

AP News. Doctors Without Borders permanently closes its emergency center in Haiti’s capital. 16 October 2025. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/haiti-msf-doctors-without-borders-center-closes-violence-68595071309e258e9c67ca233eb31822

Sudan civil war escalation:

United Nations press release. (2025, April 14). As Sudan’s brutal conflict enters third year, Secretary-General demands renewed focus, end to weapons flowing into country, stressing civilians paying highest price. https://press.un.org/en/2025/sgsm22624.doc.htm press.un.org

BBC News article

BBC News. (2025, November 13). A simple guide to what is happening in Sudan. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cjel2nn22z9o

Al-Jazeera, video. (2025, December 4). Sudan war explained. https://www.aljazeera.com/video/start-here/2025/12/4/sudan-war-explained-start-here

Al-Jazeera. (2025, March 28). Sudan army claims taking full control of capital Khartoum. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/3/28/sudan-army-claims-taking-full-control-of-capital-khartoum

Al-Jazeera. (2025, October 26). Battle for Sudan’s El Fasher intensifies as RSF claims seizing army HQ. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/10/26/battle-for-sudans-el-fasher-intensifies-as-rsf-claims-seizing-army-hq

The Economist. (2025, October 30). Darfur’s besieged capital falls to the Rapid Support Forces. https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2025/10/30/darfurs-besieged-capital-falls-to-the-rapid-support-forces

The Economist article. (2025, November 12). A quick, dirty, Trump-backed ceasefire is possible in Sudan. https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2025/11/12/a-quick-dirty-trump-backed-ceasefire-is-possible-in-sudan?utm_campaign=editorial-social

AUKUS expansion and Indo-Pacific security:

Pentagon launches review of Aukus nuclear submarine deal. (2025, June 11). Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/4a9355d9-4aff-49ec-bf7e-ea21de97917b (Financial Times)

US sends a shot across the bows of its allies over … (2025, June 15). Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/c1c7aa2e-9b2e-4138-a88e-d185835c12f5 (Financial Times)

Japan scraps US meeting after Washington demands more defence spending. (2025, June 20). Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/53f646e7-b4e7-4bf4-8d5d-7142b4460080 (Financial Times)

US demands to know what allies would do in event of war over Taiwan. (2025, July 13). Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/41e272e4-5b25-47ee-807c-2b57c1316fe4 (Financial Times)

Financial Times. (2025). Australia picks Mitsubishi over German rival Thyssenkrupp for $6.5bn defence deal. https://www.ft.com/content/610d7b43-ad55-4acd-904c-b22ca254995a

Financial Times. (2025). Australia rolls out ‘ghost bats and sharks’ in defence spree. https://www.ft.com/content/9223e4d7-f069-43d0-b01f-d2cb55662fad

Financial Times. (2025). Donald Trump signals backing for Aukus nuclear deal with Australia. https://www.ft.com/content/c20e6c85-1fce-4639-bcee-dea95c49a325

COP30 climate summit:

OECD (2025) The imperative of energy security: Old concerns, new challenges

https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/economic-security-in-a-changing-world_4eac89c7-en/full-report/the-imperative-of-energy-security-old-concerns-new-challenges_2c46f58d.html (OECD)

UNFCCC, UN Climate Change Conference – Belém, November 2025 (COP30)

https://unfccc.int/cop30 (UNFCCC)

Angeli Mehta (2025, November 27; updated November 28, 2025) COP30: Big pledges on renewables and industry, but ambition falters on ending fossil fuels

https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/cop-30-big-pledges-renewables-industry-ambition-falters-ending-fossil-fuels–ecmii-2025-11-27/ (Reuters)

UNFCCC (n.d.) The Paris Agreement

https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (UNFCCC)

UNEP (2025, November 4) Emissions Gap Report 2025

https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2025 (UNEP)

Valerie Volcovici (2025, October 31) US will not send officials to COP30 climate talks, White House says

https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/cop/us-will-not-send-officials-cop30-climate-talks-white-house-says-2025-10-31/ (Reuters)

UNFCCC (2023, December 13) COP28 Agreement signals ‘beginning of the end’ of the fossil fuel era

https://unfccc.int/news/cop28-agreement-signals-beginning-of-the-end-of-the-fossil-fuel-era (UNFCCC)

David Waskow et al. (2025, November 25) Beyond the Headlines: COP30’s Outcomes and Disappointments

https://www.wri.org/insights/cop30-outcomes-next-steps (World Resources Institute)

US-China tech confrontation:

BBC News (2025) China races to break Nvidia’s dominance in AI chips

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cgmz2vm3yv8o (BBC)

Fanny Potkin & Josh Ye (2025, December 22) Exclusive: Nvidia aims to begin H200 chip shipments to China by mid-February, sources say

https://www.reuters.com/world/china/nvidia-aims-begin-h200-chip-shipments-china-by-mid-february-sources-say-2025-12-22/ (Reuters)

Iran nuclear negotiations

Oliver Holmes (2025, October 18) Iran announces official end to 10-year-old nuclear agreement

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/oct/18/iran-announces-official-end-to-10-year-old-nuclear-agreement (The Guardian)

Susan A. Hughes (2025, July 9) Explainer: How the United States has approached nuclear negotiations with Iran

https://www.hks.harvard.edu/faculty-research/policy-topics/international-relations-security/explainer-how-united-states-has (Harvard Kennedy School)

David Albright & Sarah Burkhard (2022, June 1) Current Iranian Breakout Estimates

https://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/Current_Iranian_Breakout_Estimates_June_1_2022_Final.pdf (Institute for Science and International Security)

Patrick Wintour (2025, November 16) Iran says it could rejoin US nuclear talks if treated with ‘dignity and respect’

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/nov/16/iran-could-rejoin-us-nuclear-talks (The Guardian)

AFP and ToI Staff (2025, 17 December) Mossad chief: Israel has duty to ensure Iran cannot restart nuclear program

https://www.timesofisrael.com/mossad-chief-israel-has-duty-to-ensure-iran-cannot-restart-nuclear-program/ (The Times of Israel)

Images:

Drawings generated by ChatGPT

Wikimedia Commons contributors. (n.d.). Russian drone found in Ukraine [Image]. Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Russian_drone_found_in_Ukraine_04.jpg

Pexels. (n.d.). Brown and white cargo ship [Image]. Pexels.

https://www.pexels.com/photo/brown-and-white-cargo-ship-3277769/

Pexels. (n.d.). White House [Image]. Pexels.

https://www.pexels.com/photo/white-house-129112/

Pexels. (n.d.). Aerial photography of assorted color buildings [Image]. Pexels.

https://www.pexels.com/photo/aerial-photography-of-assorted-color-buildings-2898214/

Pexels. (n.d.). White flag marked near Saudi Arabia [Image]. Pexels.

https://www.pexels.com/photo/white-flag-marked-near-the-saudi-arabia-8828320/

Wikimedia Commons contributors. (n.d.). SSN-AUKUS submarine [Image]. Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SSN-AUKUS_submarine.jpg

Wikimedia Commons contributors. (n.d.). Detalle de ensayo sobre plagio generado por chatbot de IA [Image]. Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Detalle_de_ensayo_sobre_plagio_generado_por_chatbot_de_IA.jpg

Wikimedia Commons contributors. (2025). HNLMS De Ruyter launches Tomahawk missile (March 11, 2025) [Image]. Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HNLMS_De_Ruyter_launches_Tomahawk_missile_(March_11,_2025).jpg

Wikimedia Commons contributors. (n.d.). COP30 protests [Image]. Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:COP30_-_Protests_06.jpg

Wikimedia Commons contributors. (2023). U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin hosts Australian and UK defence ministers at Moffett Field [Image]. Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AUKUS_-_U._S._Secretary_of_Defense_Lloyd_Austin_hosts_Richard_Marles_MP,_Deputy_Prime_Minister_and_Minister_of_Defence,_Australia,_and_Grant_Shapps,_Secretary_of_State_for_Defense,_United_Kingdom_at_Moffett_Field,_California_on_December_1,_2023.jpg

Pexels. (n.d.). Close-up of a computer circuit board [Image]. Pexels.

https://www.pexels.com/photo/close-up-of-a-computer-circuit-board-34924856/

Wikimedia Commons contributors. (2023). Islamic Republic of Iran Army Day, Mashhad [Image]. Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Islamic_Republic_of_Iran_Army_Day,_2023,_Mashhad_(050).jpg

Pexels. (n.d.). Industrial optical switch with cabled connectors [Image]. Pexels.

https://www.pexels.com/photo/industrial-optical-switch-with-cabled-connectors-4280696/Wikimedia Commons contributors. (n.d.). Parade of military motorcyclists in Kermanshah [Image]. Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parade_of_military_motorcyclists_in_Kermanshah_(03).jpg

Leave a comment