By Félix Dubé

In July 1956, the first car produced locally in the People’s Republic of China rolled off the assembly line at First Automobile Works (FAW) in Changchun [1][2]. By that time, the United States and Western Europe had already spent decades building the automotive industry into a pillar of their economies, dating back to the late 19th century.

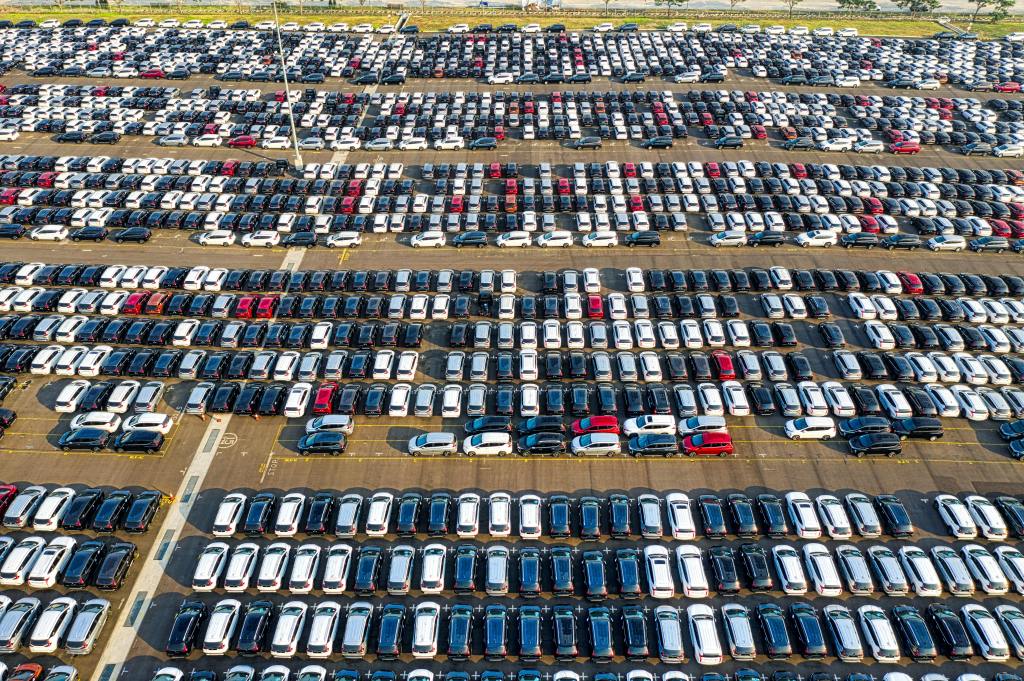

Nearly seventy years later, China is now leading the way. In 2023, China became the world’s leading vehicle exporter, overtaking Japan, which had dominated exports for decades [3]. At the same time, through government subsidies and colossal investments, China has also established itself as the central force in electrification, producing more than half of the world’s electric vehicles and leveraging this position to rapidly expand in the young electric car market [4].

Indeed, in Europe, this change is becoming much more tangible. Chinese brands, once marginal or non-existent, are now increasingly visible, especially in large cities [5]. In one year, Chinese automakers have more than doubled their share of the European market, even as the European Union reaffirmed its tariffs and planned investigations aimed at slowing the influx of Chinese electric vehicles [5][6][7]. This raises the question of what China’s automotive strategy is and what it means for the future of the automotive industry in Europe and for China’s geopolitical ambitions.

Firstly, China’s growth is mainly based on its size. Several years ago, the country became the world’s largest automotive market, and this huge domestic demand has had a snowball effect on production, supply chains, and distribution [11]. In particular, this has reduced unit costs, accelerated learning, and attracted foreign suppliers and talent.

Beijing then considered electrification to be more than just an environmental policy, but rather the nerve center of its strategy. For years, the Chinese state has used industrial and financial aid to accelerate the development of “new energy vehicles” [4]. In particular, the government has distributed numerous subsidies, tax breaks, land benefits, and energy pricing advantages [4]. This has resulted not only in a rapid transition by consumers to electric cars in the domestic market, but also in the establishment of a production system designed to outperform global competitors in terms of volume, cost, and speed [4].

Moreover, foreign partnerships have been another pillar. The era of Chinese joint ventures, during which European, American, and Japanese manufacturers such as Stellantis, Volkswagen, Ford, and even Toyota built cars in China alongside local partners, was not limited to vehicle assembly, but also included the transfer of knowledge, processes, and industrial know-how in general [4]. Thanks to this, Chinese manufacturers were able to gradually develop their own vehicles: “Made in China and by China,” these vehicles, based on the knowledge of European companies, were sometimes even accused of plagiarising foreign cars, as the designs were extremely similar [8][9]. Finally, the timing of the transition from combustion to electric power worked in China’s favor. In addition to being a new technology, electric cars are more dependent on batteries, software integration, power electronics, and supply chain control, areas in which China invested early and excels [4]. This enabled Chinese manufacturers to mass-produce very early on and flood the entire market [4]. Today, when we talk about electric vehicles, the first names that come to mind are Tesla and Chinese manufacturers such as BYD and Geely [10].

Faced with the Chinese electric giant, it seems that Europe has no clear solution. Even if the arrival of new Chinese brands were not a problem, the fact is that modern electric vehicles are defined by components and an industry in which China wields considerable influence, particularly in the areas of batteries and processed minerals [4]. Over 70% of all EV batteries ever manufactured were produced in China [10]. The batteries in these cars represent a significant portion of the total manufacturing cost [4]. China’s advantage therefore also lies in its dominance of this industry [4]. This structure gives Chinese producers a sustainable advantage in terms of price and scale, an advantage that can be deployed on a global scale [4].

This leads to a European paradox: even if European consumers do not buy Chinese-brand cars, many European cars are increasingly dependent on supply chains, components, and technologies linked to China [4]. In other words, China is the winner on every scale and can easily compete with other companies in what could be described as almost unfair competition.

As a result, the EU has turned to anti-subsidy investigations and tariff measures targeting Chinese electric vehicles in order to reduce the price gap that state support and supply chain dominance can create [6][7]. But tariffs are not an ideal solution. They can be absorbed by manufacturers, transferred to other production channels, or offset by structural cost advantages [4]. And even if they slow down the most direct forms of competition, they do not solve the problem at its source: the almost absolute dependence on Chinese industries [4]. Furthermore, the EU’s ambitious plan to switch to 100% electric cars by 2030, although controversial, greatly favors China and may weaken European manufacturers [12].

However, European car manufacturers still have some advantages, including trusted brands, dense dealer networks, and consumer relationships established over decades [4]. Chinese brands still face many obstacles outside their domestic market, including lower brand awareness, questions about residual value, after-sales service networks, and a lack of reputation [4].

Moreover, cars are not just an export product. They are also a strategic product: they are the cornerstone of employment, technological capabilities, data and software ecosystems, and industrial sovereignty [4]. For Europe, the main fear is not simply losing market share, but above all becoming structurally dependent in one of the most important industrial sectors, linked to economic resilience and long-term technological leadership [4].

Beyond the economy, there is a soft power dimension. Cars are much more than just consumer products; they are cultural artifacts: they shape the lifestyle and even the social identity of their owners. If Chinese brands become commonplace and then admired in Europe and elsewhere, this visibility will give them prestige and influence. China’s goal is to export an image of Chinese technology as innovative, desirable, and perfectly legitimate as the best in the world [4]. In the long term, the creation of a Chinese “automotive culture” could be established and become a significant asset for China’s international influence, which partly explains the Chinese government’s heavy involvement in this essential industry [4].

Therefore, thanks to its government strategy and industry, China is now on track to become the world’s largest automotive nation [3][4]. However, in the end, Chinese manufacturers are unlikely to fully displace Europe’s established brands, because a car isn’t just a practical purchase, it is a social signal. True or not, the car you drive still communicates status, taste, and a certain idea of success. That’s because legacy brands such as Ferrari, Porsche, BMW, Audi, Toyota, or Bentley carry decades of image and history—performance, luxury, safety, durability—that buyers don’t instantly transfer to newer names. So even if Chinese cars lead on price, innovation, or even sales volume, they are unlikely to eclipse the cultural and symbolic weight of these brands in the next few years.

Edited by Jules Rouvreau.

References

[1] State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (2020, July 13) The CA10 Jiefang, the People’s Republic of China’s First New Truck, is completed on July 13, 1956

http://en.sasac.gov.cn/2020/07/13/c_1869.htm (SASAC)

[2] FAW Group (n.d.) History – FAW Group

https://www.fawglobal.com/ (FAW Group)

[3] Koji Sasahara (2024, January 25) China has nudged Japan aside as No. 1 auto exporter, Japanese data show

https://apnews.com/article/fc73088d8feb7f128de2b62109a56791 (Associated Press)

[4] Enrique Feás (2024) The economics and geopolitics of electric cars: a European perspective

http://realinstitutoelcano.org/en/analyses/the-economics-and-geopolitics-of-electric-cars-a-european-perspective/ (Elcano Royal Institute)

[5] Team JATO (2025, June 24) Chinese automakers double European market share in May

https://www.jato.com/resources/media-and-press-releases/chinese-automakers-double-european-market-share-in-may (JATO)

[6] Laura Schwarz (2023, November 2) European Union: Commission Launches Anti-subsidy Investigation into Imports of Battery Electric Vehicles from China

https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2023-11-01/european-union-commission-launches-anti-subsidy-investigation-into-imports-of-battery-electric-vehicles-from-china/?utm_ (Library of Congress – Global Legal Monitor)

[7] European Commission (2024, October 29) EU imposes duties on unfairly subsidised electric vehicles from China while discussions on price undertakings continue

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/document/print/en/ip_24_5589/IP_24_5589_EN.pdf (European Commission)

[8] Liu Li (2005, May 9) GM Daewoo files suit against Chery

https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-05/09/content_440334.htm (China Daily)

[9] Congressional-Executive Commission on China (2005, November 29) Chinese and U.S. Automakers Settle Intellectual Property Dispute

https://www.cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/chinese-and-us-automakers-settle-intellectual-property-dispute (CECC)

[10] Christian Shepherd (2025, March 3) How China pulled ahead to become the world leader in electric vehicles

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/03/03/china-electric-vehicles-jinhua-leapmotor/ (The Washington Post)

[11] (Agencies) (2010, January 11) China overtakes US as world’s largest auto market

https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/09achievements/2010-01/11/content_9306920.htm (China Daily)

[12] (Staff) (2025, July 21) EU reportedly plans 100% EV quota for fleets by 2030

https://www.electrive.com/2025/07/21/eu-repordedly-plans-100-ev-quota-for-fleets-by-2030/ (electrive)

[Cover image]: Manufacture of many modern cars in daytime

(https://www.pexels.com/photo/manufacture-of-many-modern-cars-in-daytime-5962569/) Picture by Tom Fisk (https://www.pexels.com/@tomfisk/). Licensed under Pexels (https://www.pexels.com/license/)

Leave a comment