By Arthur Descazeaud.

False photographs of babies killed, footage of raids that never happened, video game images of a shot-down helicopter, fake speeches: the misinformation war around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is raging, and social media are not helping to inform objectively. Actually, they probably contribute to exacerbating tensions.

Therefore, it is urgent to conduct a precise and unbiased historical analysis of the conflict to put all discussions back into context. The situation is far too complex to be described in a few sentences only. If one wants to understand how we reached this current culmination, it is necessary to delve into the past and get the full picture. As in many other cases, nothing is ever black or white, and the incredible diversity of actors involved over the years – ranging from States, religious leaders, businessmen, and non-state organisations – is perhaps the most relevant illustration of this complexity.

This paper attempts to provide a condensed and accurate historical evolution of the Middle East region that now comprises Israel and Palestine, spanning from the first century to today. Only then would it be possible to grasp at least some of the stakes at play and how the current crisis unfolded. However, the objective is not to detail historical events without any reflection in the background.

For this reason, the whole context will be set chronologically and through the lenses of multiple major questions often asked on this topic. Then, a second part will propose some perspectives that could help achieve a peaceful and definitive resolution of the long-lasting tensions in this region.

Hopefully, this work will allow everyone to increase their knowledge on the matter and build their opinion based on something more developed than what the media accustom us to see every day. Ultimately, this paper is a call for peace, for all world leaders to come together and find a solution before it is too late, and for the general society to stop tearing itself apart on the basis of fake images or profoundly ideologised speeches.

The factual context in four major questions

The purpose here is not to answer unanswerable questions such as: who exactly struck the Al-Ahli hospital in Gaza City or where is the war between Israel and Hamas going? These questions are important, but the objective here is to take a step back and address the conflict from a higher perspective, to foster reflection, and lay the basis for future works on the topic. To do so, we will propose four different questions that do not always dominate current debates or publications, even though answering them first is key to developing a comprehensive and solid reasoning.

Was this conflict born in the 20th century?

Definitely not. Its roots are a lot older, and it would actually be a mistake to talk about one single conflict: the region has been the theatre of envies from a diversity of actors since the very beginning.

Map of Judea at the beginning of the Christian era [1]

This is the map we will use as a starting point to talk about Israel – Palestine relations for three reasons: it represents a time far enough from today, the information we have from historians of that period seems quite reliable, and it already underlines the complexity of the situation.

So we will start at the 1st century BCE, back when the Roman Empire arrived in the region, and created the province of Syria (North part of the map) in 64 BCE, while annexing Egypt (South part of the map) in 30 BCE. The kingdom of Judea (in purple) managed to keep its independence until 4 BCE, when Herod the Great died, and the area was divided among his three sons (purple, light blue and dark blue) and his sister (green). The Romans maintained their military pressure and in 4 BCE, took control of the part managed by Herod Archelaus (purple), and administered it as an annex of the province of Syria to start with. Over the years, the empire kept developing and between the years 129 and 130, the emperor Hadrian turned Jerusalem into an official Roman colony called Aelia Capitolina.

The presence of the Romans in the region is important because it marks the beginning of the persecution of the Jewish populations there and consequently, the birth of a Jewish diaspora all around the Mediterranean Sea. The development of this diaspora should be seen as an ongoing flow throughout history: not all Jews left when the Romans first arrived. The fact that some of them stayed led to rising tensions between their community and the governing Romans, and to a first revolt in 70 BCE by the Zealots – a group of Jews that thought they only owed obedience to God – which resulted in the destruction of the Second Temple. Such an act was not only of significant religious importance for the Jews but also a symbolic demonstration of power from the Romans given the size (the highest wall measured around 45,72m and its smallest stones weighted between two to five tons) and grandeur of the Temple [2]. Between 132 and 135, the city then witnessed outbreaks of violence and became the theatre of the second and last Jewish revolt led by Shimon Bar Kohba. As a result, the Romans integrally destroyed Jerusalem, and forced the remaining Jewish community who had not been killed or enslaved to flee. It is believed that approximately 25% of the Jewish population has been exterminated and 10% enslaved. The rest fled to Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq), and to Mediterranean lands such as southeastern Spain, southern France, southern Italy and Greece [3]. At this time, Judea is renamed Syria Palaestina. This is where the modern word Palestine comes from.

But history does not stop there. After the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity, which started in 312 with emperor Constantine I, the Persians, helped by the Jews, took back in 614 the city that had already been rebranded as Jerusalem by the Romans. Both Jews and Persians killed around 60,000 to 90,000 Christians during this episode [4], and more symbolically, the Persians stole the True Cross [5] – the cross on which Jesus of Nazareth was crucified according to Christian tradition. This event is very interesting because the Persian empire was at the time composed of a vast majority of Zoroastrians [5], an ancient pre-Islamic religion that was born in what would now be Iran [6]. This reinforces the point stating that today’s conflict between Israel and Palestinians is, in reality, part of a long period of conflicts and tensions between changing alliances depending on the circumstances.

However, although the Persians first let the Jews run Jerusalem, the murder of their leader Nehemiah ben Hushiel in 614 during a local Christian revolt altered the situation, ultimately causing the Persians to break their pledge by forbidding Jews to settle within a three-mile radius of Jerusalem [7]. Sources seem to agree on the fact that the Jewish community was not violently expelled from the city, but the rule was clear. And in 620, Jerusalem became the third holy place of Islam, behind Mecca and Medina.

However, when the Roman emperor Heraclius conquered the city back in 628, he changed the Persian policy. He expelled both Persians and Jews – something quite logical, given that the latter had attacked the Romans together in 614. Ten years later, though, it was the Muslim’s turn to take control over Jerusalem and to build the first Islamic cult site between 640 and 660 where the Al-Aqsa mosque is now situated. In 1047, they renamed the city al-Quds (Holy city) and although the region has not been exempt from tensions between Sunni and Shia Muslims, this 638-1186 period has anchored the importance of Jerusalem in Islam – which will have repercussions until today. Although under Muslim control, other religions were tolerated as long as they respected the Pact of Umar, a document detailing the conditions in which Christians and Jews would be allowed to live and worship [8]. The rules detailed in this pact were not associating non-Muslim persons as first class citizens under the caliphate, but set protections for the “People of the Book.” For instance, by abiding by the restrictions listed in the Pact, non-Muslims were granted the security of their persons, their families, and their possessions [9].

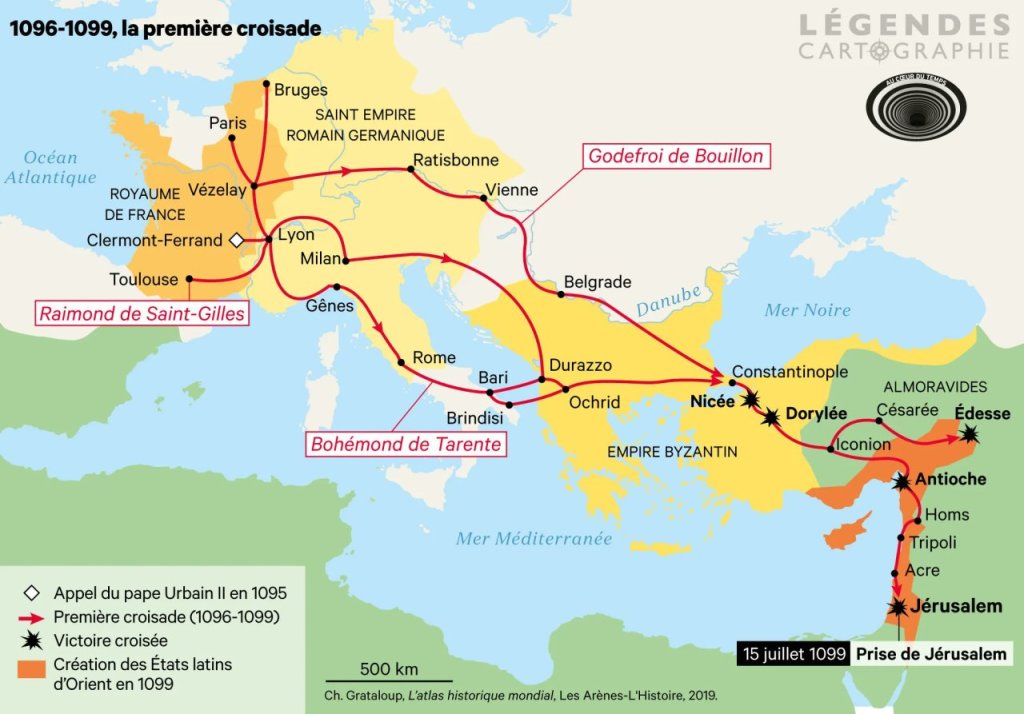

However, the different desires to control the area did not stop with the Muslims in power. In 1099, it was the European crusader’s turn to take the city at the end of the First Crusade, which followed the call of 1095 from Pope Urban II. The purpose was for the Occident to take back Jerusalem given how the Christian community was being treated there [10], though some historians argue that the anti-Christian acts that were depicted by the Pope were exaggerated [11].

1096-1099, the First Crusade [12]

As shown on the map, this crusade was followed by the establishment of four Crusader States in order to keep the territorial gains in the Middle East, among which the most important was the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Numerous religious monuments such as churches and monasteries were built in the city during this time. For example, a church was built in Kildron valley to mark the place of the Virgin Mary’s tomb [13] [14]. However, only a small portion of the army that had conducted the First Crusade stayed in the region. It is important to note that, although the Muslim governor has been authorised to leave Jerusalem with his army after surrendering, the crusaders did not hesitate to slaughter or imprison both Muslim and Jewish civilians when entering the city [10]. Nevertheless, crusaders quickly understood that they needed to keep the diversity of their states’ populations in order to stay in power [15]. This is why it was decided that non-Christian religions shall be tolerated, although subject to discriminatory laws and taxes (which were still lower than in previous Muslim-controlled areas) [15]. In parallel, southern Spain was invaded in 1147 by the Almohads: a new Berber dynasty from North Africa which replaced the Almoravids. Their imposition of Islam in the region forced both Christians and Jews (among whom at least some were descendents of those who had fled Jerusalem at the first century BCE) to flee to northern Christian Spain [16].

After the Crusader states, control over the area moved to the sultan of Egypt Saladin in 1187, but he left the Holy Sepulchre to Christians and gave back their synagogues to the Jews. Muslims and Christians then took turns conquering and ruling the city until 1516, when Jerusalem was conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Meanwhile, it should not be forgotten that antisemitism was rising in many European countries and that Jewish communities were often, if not persecuted, strongly discriminated against. For example, the estimated 3000 Jewish people living in England in 1290 were all expelled from the country on the orders of Edward I [17], and the entire Jewish population of France was expelled and saw its lands confiscated by the government in 1306 [18]. In the case of Spain, although Jews did their best to create some form of “convivencia” (co-existence) with the Christians in a Spanish kingdom that “had been anti-Jewish for centuries,” [20] their attempts to assimilate have consistently been rejected and in 1492, after King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile defeated the last Iberian Muslim presence in Granada, the Jewish community was presented the choice to either leave, convert to Catholicism, or be executed [19].

Back to the Middle East now, all three religions cohabited together under Ottoman rule, and the area developed a lot through the launch of infrastructure projects such as the installation of electrical lighting and the inauguration of a railway. Jews were given quite a lot of freedom and, although their inferiority was stressed in the Islamic rulings, they were protected by the law and recognised for their business abilities [20]. In addition, considering that the Ottoman Empire was one of the most advanced, best-administered and tolerant states in the world at that time, and that anti-Semitic measures were spreading in Europe, many Jews decided to flee towards the Ottoman region.

All Great European powers had installed consulates in Jerusalem and problems strengthened with the World War I declaration . Indeed, the Ottomans being German allies, the consuls from the Triple Entente were expelled and the Ottoman army was tasked to attract as many enemies as possible on itself to relieve the pressure on the German army. Although heavily defeated at the end of the war, the Ottomans successfully managed to open new fronts with the British and Russian armies, and also helped their allies by sending expeditionary corps to the campaigns in Eastern Europe [21].

The year 1917 represents a turning point in the region as the Sykes-Picot Agreement is publicly revealed. This was a secret convention negotiated by France, Great Britain and Russia between 1915 and 1917, in which they decided the fate of the Ottoman Empire, if they were to win the war. Leon Trotsky, after the Bolshevik communists had overthrown Russian Tsar Nicholas I, found a copy of the Sykes-Picot agreement in the government’s archive records [22], and published it. This was felt as a real betrayal by the Arabs who had been promised by the British that they would become independent if they helped defeat the Ottomans [23]. Indeed, the secret Hussein-McMahon Correspondence between 1915 and 1916 gave independence guarantees to the King of Hejaz, and for this reason he worked on convincing the Arabs of the Hejaz to revolt against the Ottomans. Hussein’s initial desire was an Arab nation spanning from Syria to Yemen with himself as the caliph, but the British had different plans which would unfold in the years following the end of the war [24].

Wrapping it up, it is clear that the current conflict over this area did not arise not out of the blue. It is part of a long history of tensions involving an incredible diversity of actors. Now that the general frame is set, the following questions will help us understand the specificities of today’s conflict between Israel and the Palestinian people.

Edited by Justine Peries.

References

[1] Map of Judea at the beginning of the Christian era, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution License.

[2] “Dimensions of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem.” LaurelhillСemetery.blog, https://laurelhillcemetery.blog/what-were-the-dimensions-of-the-jewish-temple-in-jerusalem-2359/. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[3] Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida. “Jewish Displacement.” Florida Center for Instructional Technology, https://fcit.usf.edu/holocaust/people/displace.htm. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[4] “Heraclius.” Jewish Virtual Library, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/heraclius. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[5] Van Gogh, Vincent. “Persian | People, Language & Religion.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Persian. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[6] Duchesne, Jacques. “Zoroastrianism | Definition, Beliefs, Founder, Holy Book, & Facts.” Britannica, 8 November 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Zoroastrianism. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[7] Jewish Virtual Library. ““Medieval” Period in the West (ca. 600-1500).” Jewish Virtual Library, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/8220-medieval-8221-period-in-the-west-ca-600-1500. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[8] Islam and the Jews: The Pact of Umar, 9th Century CE, https://www.bu.edu/mzank/Jerusalem/tx/pactofumar.htm. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[9] Jewish Virtual Library. “The Pact of Umar Regulating the Status of Non-Muslims Under Muslim Rule.” Jewish Virtual Library, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-pact-of-umar-regulating-the-status-of-non-muslims-under-muslim-rule?utm_content=cmp-true. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[10] Eychenne, Mathieu. “La prise de Jérusalem par les croisés en 1099.” Magazine Histoire & Civilisations, 27 January 2022, https://www.histoire-et-civilisations.com/thematiques/moyen-age/la-prise-de-jerusalem-par-les-croises-en-1099-80415.php. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[11] “Pope Urban II orders first Crusade.” Pope Urban II orders first Crusade | November 27, 1095 | HISTORY, 24 November 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/pope-urban-ii-orders-first-crusade. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[12] Atlas historique mondial ©Les Arènes/L’Histoire, Paris, 2023. Cartographie : Légendes Cartographie.

[13] Browns, Shmuel. “Crusader Jerusalem.” Israel Tours, 24 April 2013, https://israel-tourguide.info/2013/04/24/crusader-jerusalem/. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[14] Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities. “The Tomb of the Virgin Mary.” Travel Palestine, 25 September 2017, https://www.travelpalestine.ps/en/article/17/The-Tomb-of-the-Virgin-Mary. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[15] Cartwright, Mark, and Christopher Tyerman. “Crusader States.” World History Encyclopedia, 1 November 2018, https://www.worldhistory.org/Crusader_States/. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[16] Gerber, Jane S. ““Ornament of the World” and the Jews of Spain | The National Endowment for the Humanities.” The National Endowment For The Humanities, 17 December 2019, https://www.neh.gov/article/ornament-world-and-jews-spain. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[17] University of Oxford. “Why were the Jews expelled from England in 1290?” Faculty of History, https://www.history.ox.ac.uk/why-were-the-jews-expelled-from-england-in-1290-0. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[18] History. “King Charles VI of France orders all Jews expelled from the kingdom.” King Charles VI of France orders all Jews expelled from the kingdom, 12 November 2019, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/king-charles-vi-of-france-orders-all-jews-expelled. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[19] Restaino, Michelina. “The 1492 Jewish Expulsion from Spain: How Identity Politics and Economics Converged.” Digital Commons@Georgia Southern, 17 April 2018, https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1401&context=honors-theses. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[20] Birnbaum, Marianna D. “The Long Journey of Gracia Mendes – Chapter 7. The Ottoman Empire and the Jews – Central European University Press.” OpenEdition Books, https://books.openedition.org/ceup/2139?lang=fr. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[21] Baş, Mehmet Fatih. “Warfare 1914-1918 (Ottoman Empire/Middle East) | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1).” 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, 22 July 2019, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/warfare_1914-1918_ottoman_empiremiddle_east. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[22] Al Jazeera. “A century on: Why Arabs resent Sykes-Picot.” A century on: Why Arabs resent Sykes-Picot, https://interactive.aljazeera.com/aje/2016/sykes-picot-100-years-middle-east-map/index.html. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[23] “Sykes-Picot Agreement | Map, History, & Facts.” Britannica, 17 November 2023, https://www.britannica.com/event/Sykes-Picot-Agreement. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[24] Saud, Abdulaziz Ibn. “The Arab Revolt – School of English.” Birmingham City University, https://www.bcu.ac.uk/english/research/stories-of-sacrifice/virtual-tour/the-arab-revolt. Accessed 28 November 2023.

[Cover image] Photo of the Dôme Du Rocher, Jérusalem by Becca Siegel, licensed under CC.

Leave a reply to An objective historical analysis of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and potential perspectives to walk towards peace: Part 2 – ESCP Politics & Public Policy Society Cancel reply