A few days ago, I was walking through the graves of Lychakiv Cemetery in Lviv, Ukraine, for the second time, as part of one of my volunteering trips to the country. I wanted my friend who had accompanied me there to discover this must-see site of Galicia that encapsulates the region’s complex history over the past two centuries and which deeply struck me on my first visit.

One of the most iconic sections of the graveyard is the Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów[1]. It constitutes the burial place of the slain during the post-WWI hostilities in the region – mostly Poles[2] – which lasted from 1918 to 1920. Given Moscow’s ongoing aggression against Ukraine (2014–present), one might mistakenly assume these rows of graves are another result of Russian imperialism that Ukrainian authorities aimed to highlight in their struggle against the Kremlin. But Lviv’s rich history in the 20th century makes it a bit more complicated. Some of those buried there were indeed victims of the Polish-Soviet War (1919–21) [3]. But another large section contains the remains of soldiers and volunteers who died during the Polish-Ukrainian War (1918-19) while pushing Poland’s claim on Galicia against Ukrainian nationalists[4].

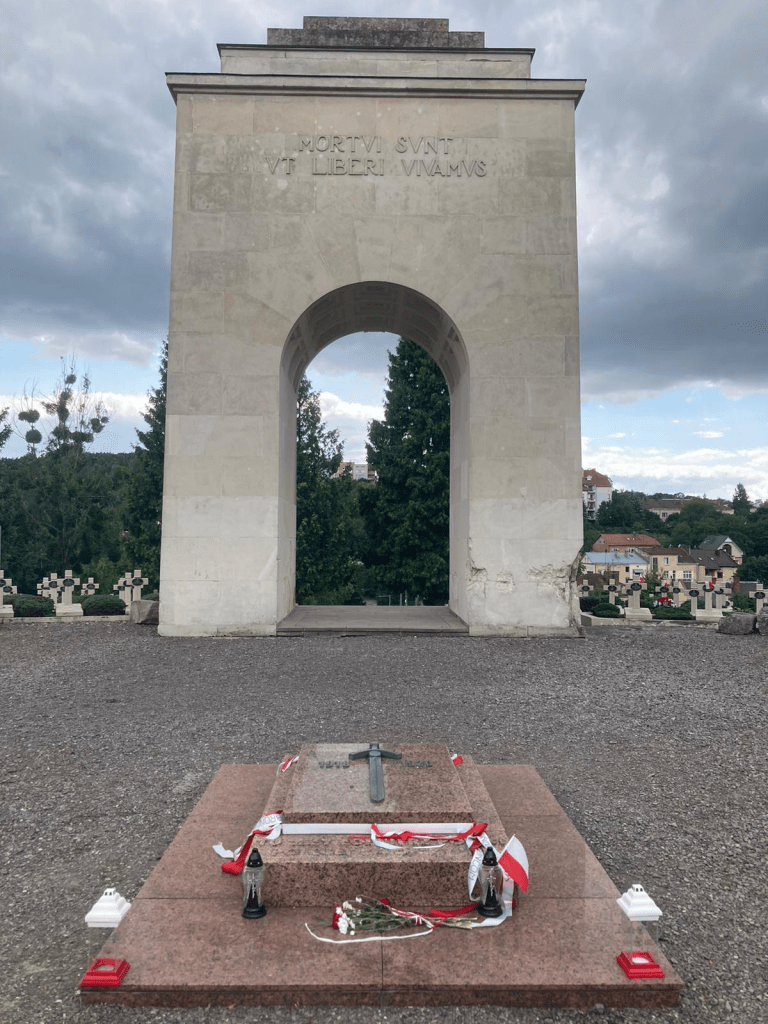

Put another way, one of the most famous sites to visit in wartime Lviv – a place often viewed as the “hotbed of Ukrainian nationalism”[5] – is nothing more than a necropolis partly honouring fallen opponents of Ukrainian independence. Such oddness gets even more striking when one moves away from the said spot and walks towards the monument towering over the trees, surrounding the tombs (see picture). You are back in one of the cemetery’s Ukrainian ‘sectors’ and only a narrow knowledge of Cyrillic is required to understand most of the acronyms written on the tombstones. First comes the memorial dedicated to the soldiers of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (УСC; 1914-18) as well as the Ukrainian Galician Army (УГА; 1918-19)[6]. Then stairs leading to the latest division of the cemetery revering the most recent Heroes of Ukraine.

One would guess this sector to only concern Ukrainian defenders killed by pro-Russian separatists amidst the Donbas war (2014-22) and, since 2022, by Russia itself. But by looking closely to the right – something I had for some reason not done on my first visit – the stone crosses look more worn out. A glance is enough to distinguish the three letters ‘У-П-А’ (UPA) engraved on many of them, meaning that those resting there were members of the highly controversial Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the military branch of Stepan Bandera’s Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN-B) founded in late 1942 [7].

In Latin: “They died so we could live free.”

The main purpose of this work is neither to revisit the place of Bandera and the Banderites in modern Ukraine’s collective memory – although it is patently positive in Western Ukraine since the fall of the USSR, especially in Lviv – nor to address Russian propaganda’s many lies on the matter following the Revolution of Dignity (2014). Yet, Ukrainian nationalists of the OUN-UPA actively participated in the Holocaust by exterminating Jews in Galicia and Volhynia [8], for instance during the Lviv pogroms of summer 1941 [9] [10]. The fact that monuments were built in their remembrance in today’s Ukraine raises legitimate questions and concerns, hence the need to make a few points to ensure clarity for the reader.

No, Ukraine is not a neo-Nazi state worshipping Bandera and his associates, even though this is what the Kremlin would like people to believe to legitimise its full-scale invasion of 2022. The curious rehabilitation of Bandera within Ukrainian society falls under a far more complex, incremental process. Its roots can be traced back to the end of WWII and lie on a combination of factors.

First, the assassination of Bandera by the KGB in 1959 and the backlash of Soviet hostile propaganda targeting Ukrainian nationalism – both of which contributed to the mythologisation of Bandera in the collective imagination[11], sometimes as a martyr. Second, eight decades of often deceitful nationalists and extremists’ efforts to polish and popularise his image[12]. Third, a rehabilitation-friendly climate fostered by the ‘memory war’ ongoing between Moscow and Kyiv since the mid-2000s – a conflict that led Ukraine to progressively build a nationalist anti-Russian narrative [13], originally under the leadership of President Yushchenko (2005-10)[14] and ultimately through the ‘decommunisation laws’ of 2015 [15] enacted as both a symbolic and escalated response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and support to Donbas separatists.

The provocative trend of reappropriating modern Russian propaganda – seen notably among the Ukrainian youth protesting on the Maidan – through an ironic and blind glorification of Bandera’s historical figure has also assisted in completing such rehabilitation. It paved the way to acceptance of legislation as explicit as the decommunisation laws within Ukrainian public opinion [16]. It is nevertheless important to note that the sole goal of this trend has always been to mock and defy Putin’s exaggerated narrative claiming that anyone supporting the idea of a Ukraine freed from Russian influence must necessarily be a Banderite, rather than to genuinely promote Bandera or his ideas. In fact, the popularity of Bandera and other prominent nationalists increased sharply within Ukrainian society only after the outbreak of the war in 2014, and even more so following Moscow’s launch of its ‘Special Military Operation’ to precisely ‘denazify’ Ukraine [17].

In other words, it is true that Bandera’s heritage is still authentically defended and celebrated by the Ukrainian nationalist far-right – a political family without any real influence on the national political stage since the 1991 independence [18]. However, most so-called defences of OUN–UPA by ordinary Ukrainians are, at worst, zealous provocations directed against Putin’s Russia and its propaganda in the harsh context of war, and, at best, signs of an almost complete lack of awareness of Ukraine’s own history [18] – in particular the role of Banderites in atrocities and their brief, opportunistic collaboration with Nazi Germany. In sum, the remembrance of Bandera in contemporary Ukraine operates as a largely selective phenomenon, with Ukrainians sincerely perceiving him as a key fighter advocating for the country’s freedom and liberation from Russia – a cause that naturally resonates given the current context – while fully disregarding any other facets of his life and legacy, often out of ignorance [19].

The discussion now refocuses on the initial topic introduced earlier: the startling proximity of a Polish military cemetery celebrating the fight for Poland’s freedom less than two hundred meters away from monuments commemorating 20th-century OUN-UPA nationalists. Indeed, the UPA is not only controversial for the pogroms perpetrated by its partisans in Galicia and Volhynia from 1941 to 1945; it is also responsible for hate crimes against Poles in the same area [20], namely massacres carried out against Polish settlements between 1943 and 1945, which resulted in around 100,000 deaths. These events are considered ethnic cleansing by historians like Timothy Snyder [21], while Poland now officially refers to them as genocide [22] despite the prevailing scholarly consensus rejecting their genocidal character. In Ukraine, they are euphemistically referred to as the ‘Volyn tragedy’.

OUN units’ actions during the Second World War can be explained by the organisation’s doctrine, which designated three principal enemies: Soviets, Poles and Jews [23]. OUN-UPA fighters sought to purge the territory of a prospective Ukrainian state of these groups (and “other enemies”) [23], with a notable tendency to prioritise Russians and Poles over Jews [24] – the former as occupiers of Ukraine, the latter as responsible for the repression and forced ‘Polonisation’ of Ukrainian population in interwar Poland’s southeastern regions [25]. This grievance towards Poles remains vivid in Ukrainian historical memory today [26].

This raises questions about the long-term repercussions of these stark events on Poland-Ukraine relations since the end of WWII, particularly amidst the Russo-Ukrainian War and the persistent absence of formal apologies from the Ukrainian government [27]. How to come to terms with a past that continues to cast its shadow at a time when Kyiv is seeking closer integration with the EU, and relies heavily on Warsaw’s support to advance its candidacy?

From the end of the Second World War to Ukraine’s independence in 1991, Polish-Ukrainian relations were nonexistent, with all matters concerning communist Poland and the Ukrainian SSR handled directly in Moscow [28]. In the absence of any bilateral dialogue, each side cultivated its own propaganda and narrative diabolising the other and accentuating its wrongs [28]: Poland mostly framed its account around the OUN-led massacres during the war, whereas Ukraine underscored the historically unjust or brutal treatment of Ukrainian populations under Polish authority. This resentment can be traced from the era of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795) [29] to the post-war forced resettlement of 140,000 Ukrainians from southeastern Poland to the country’s western and northern territories during Operation Vistula (1947) [30].

Still, at the end of the 1970s, the governments-in-exile of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (1917-21) [31] and pre-war Republic of Poland (1918-39) signed an agreement in London that laid the groundwork for Polish-Ukrainian cooperation [32]. Thanks to these joint efforts initiated from abroad – including those of the banned Catholic clergy which set up meetings between Polish hierarchs and representatives of the Ukrainian Uniate (Eastern Catholic) Church – bonds between the two countries’ opposition movements and intelligentsias had rapidly grown by the end of the 1980s [32]. As the Polish democratic regime rose from its ashes on these bases of reconciliation, the news of Ukrainian independence in 1991 was largely welcomed in Poland. Warsaw was the first capital to recognise Ukraine’s sovereignty, a treaty of friendship and coordination was signed in 1992, and many efforts were made throughout the 1990s to expand the Polish-Ukrainian partnership [32]. Since then, Warsaw never stopped to be a vocal advocate for Ukraine’s integration into EU and NATO.

As for the many questions of memory that had thus far remained entirely unanswered, progress was achieved. In 1997, Presidents Kwasniewski and Kuchma signed together a ‘reconciliation declaration’ that instantly became the pillar of the renewal of Polish-Ukrainian relations and aimed to “overcome a history of rivalry and bloodshed dating from the 17th century” [33]. On a more local scale, it is interesting to note that even though many of the graves in the Lwów Eaglets cemetery – another name of the Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów – are the ones of Polish soldiers who fought Ukrainian nationalists during the war of 1918-19, the Polish government managed to convince Lviv regional authorities to reopen the site in 2005. They did so partly to reward Poland for its support of the pro-European Orange Revolution (2004), but also out of a conscious recognition that genuine and thorough reconciliation was necessary [34]. The site had been abandoned under Soviet rule and turned into a truck depot before reconstruction works were initiated by Polish nationals in anticipation of the collapse of the Communist bloc.

Yet, the darkest chapters of shared history are far from forgotten. While it is undeniable that Polish-Ukrainian friendship endures and that bilateral cooperation between Kyiv and Warsaw has only deepened in the 21st century, the fact remains that Ukraine’s 2015 “decommunisation laws” reignited the almost-dormant conflict of memories. A renewed escalation in the latter half of the 2010s – worsened by the Polish national-populist PiS party’s rise to power – led Poland to advance a narrative portraying the UPA-led massacres as genocide. Tensions flared over issues such as the exhumation of Polish victims – a process abruptly prohibited by the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance in 2017 in response to several anti-Ukrainian acts against UPA monuments in Poland [35].

Ultimately, efforts to address the Polish-Ukrainian challenges of historical remembrance appeared to stagnate despite continued symbolic gestures like President Poroshenko’s 2016 visit to Warsaw to kneel before the monument to the massacres’ victims [36] or the joint commemoration by Presidents Zelensky and Duda in 2023 [37].

In the context of its war of aggression against Ukraine, Russia repeatedly tried to use this point of contention between Kyiv and Warsaw to weaken their alliance. Senior officials of the Polish government publicly acknowledged these Kremlin’s intentions: they cleverly leveraged them to press the Ukrainian side to hasten the process of exhumation and to make it recognise OUN-UPA’s crimes as more than a mere ‘tragedy’. Former Poland’s Prime Minister Morawiecki declared in 2023: “We must be aware, Poles and Ukrainians, that without the full clarification and full record of the Volhynia crimes, Russia will always be using this card to drive a wedge between Poles and Ukrainians” [38].

Therefore, it appears Moscow’s efforts are confronted with the sturdiness of Polish-Ukrainian relations and have proven largely ineffective despite the latter’s abiding Achilles heel. Influential Polish ministers currently in office – like Defence Minister Kosiniak-Kamysz [39] – have insisted that Warsaw’s support to the defence of Ukraine amid the Russian full-scale invasion should not be conditioned upon progress in reconciliation and memory. Meanwhile, President Zelensky and Prime Minister Tusk finally reached an agreement in January 2025 to resume exhumations of victims [40], thus putting an end to a decade-old dispute. Zelensky emphasised: “We are neighbours and our biggest threat is Russia and this is a threat now, here and tomorrow. We should do everything to make our cooperation stronger” – a reminder that the absolute priority for both Kyiv and Warsaw is defeating Vladimir Putin rather than triggering protracted altercations over the Volhynia question.

In short, Polish–Ukrainian relations since 1991 have been marked by repeated ups and downs. They are likely to remain strained as long as Ukraine frames the ‘Volyn tragedy’ as just another episode of a symmetrical conflict, instead of recognising that the scale of UPA operations and the toll on Polish civilians reveal something far more one-sided and violent than ordinary inter-ethnic clashes [41]. For its part, Warsaw remains far from reaching the point in which it would trade military support to Kyiv in exchange for accelerating remembrance works in Ukraine. However, the Polish government shows no inclination to do its Ukrainian counterpart any favors as to its EU and NATO candidacies. Polish conservative newly-elected President Nawrocki – a former head of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance – announced that “he won’t support Ukraine’s bids to join NATO and the EU until the discord over the legacy of the massacres in Volhynia is resolved” [42]. A similar stance is shared among government ministers, starting with Kosiniak-Kamysz who said in late 2024: “Ukraine will not join the European Union […] unless the issue is settled, exhumations are carried out, and proper commemoration takes place” [43]. Yet, ‘settling the issue’ in Warsaw’s perspective will probably have to include a move back from the Ukrainian government regarding the decommunisation laws granting public recognition to OUN-UPA members. This is something unlikely to happen while the war against Russia is still raging, since the “legend of the UPA serves to boost Ukraine’s wartime morale, something that Ukrainians cannot afford to neglect” according to Jan Piekło, former Polish ambassador to Kyiv (2016-19) [43].

In the end, Lychakiv Cemetery is a heritage of Polish-Ukrainian relations on its own. It epitomises the paradoxes of Kyiv–Warsaw relations. On one hand, the beauty and elegance of its most famous section is the fruit of a 15-year-long bilateral cooperation to renovate it from scratch and honour the memory of Polish victims of the centenarian Polish-Ukrainian War on present day Ukrainian soil – a strong indicator of reconciliation. Conversely, the presence of nearby monuments perpetuating the legacy of controversial historical figures (and groups) despite repeated calls to concede their indisputable responsibility for atrocious crimes points out the lack of serious remembrance work in Ukraine. This is a very unfortunate assessment since both countries suffer as a result: Polish victims of these acts of violence along with their descendants continue to lack proper recognition and answers, while Ukrainians – for most of them, unconsciously – are confining themselves to a vicious circle of glorification of war criminals. This dynamic is likely to impede the country’s EU integration, strain relations with Warsaw and carry on for years even after the war has ended.

Still, one should not doubt Ukrainians’ capacity to critically confront their history in due time. This society is without a doubt one of the most resilient in the world. Facing the harsh reality of its past after resisting a barbarous full-scale invasion will be far from insurmountable. Other countries have gone through these kinds of unpleasant efforts – Germany, France, Spain – and the common lesson is clear: such processes require time. It took more than half a century for the French Republic to admit its responsibility in the Vel’ d’Hiv’ roundup of July 1942, during which approximately 13,000 Jews were arrested by French police and deported to Nazi camps. Ukrainians too should be afforded the necessary time to navigate their historical memory.

For now, the priority must be the defence against the ‘Muscovite’ invader – sometimes at the risk of conflating everything: as we were about to leave the Lwów Eaglets cemetery, we encountered an elderly Ukrainian man walking among the tombs. He began speaking to me, and I immediately pointed out my French-Ukrainian patch on my waist bag. “Frantsiya. Me volontery” (“France. We are volunteers”) I told him in broken Ukrainian. He promptly led us to the French monument of the cemetery. He turned back to contemplate the countless Polish graves surrounding us, waved his arms in their direction while simultaneously saying things I struggled to understand, and then mimed digging a grave. Repeating the gesture a second time, this time facing the French memorial, he shouted: “Bil’shovyky! Lenin! Rosiya!” – claiming that Lenin’s Bolsheviks from Russia were responsible for all these deaths, whereas a significant portion of those buried here have actually perished fighting Ukrainian nationalists.

Here in Lychakiv, memory seems to have come to a standstill. There are of course understandable reasons for this, but how long could it endure?

Last edit: 27/01/2026

Edited by Maxime Pierre.

References & Footnotes

[1] Lviv, “the city of lions” , can be spelled and pronounced in various ways: Lvov in Russian, Lwów in Polish (used for instance during the interwar period, when the city was part of Poland), Lemberg in German. This echoes its historical statute of a city at the crossroads of empires, namely Austria-Hungary and Russia.

[2] Anecdotally, two monuments of the site also honour both French and American volunteers who died for Poland between 1918 and 1920.

[3] Fighting stopped in late 1920 but a peace deal – the Peace of Riga – was only concluded in early 1921.

[4] In 1917-18, as WWI was coming to an end, the dislocation of the German and Austro-Hungarian empires as well as revolutionary Russia’s loss of control over most of its Eastern European territories led to the formation of what would become the Second Polish Republic – interwar Poland – and two short-lived Ukrainian states. The latter united against the former to gain control of Galicia, without success (1918-19). The main one of the two then abandoned the other to Polish annexation (1919) before joining the Polish-Soviet War on Warsaw’s side (1920) to fight Bolsheviks aiming to reconquer Ukraine. It was eventually crushed by communist forces and replaced by the Ukrainian SSR while Poland managed to remain free from Russian orbit (1921).

[5] Mykola Riabchuk, “The City and the Myth: Making Sense of the Lviv ‘Nationalist’ Image” Aspen Institute, March 12, 2020. www.aspeninstitutece.org/article/2020/city-myth-making-sense-lviv-nationalist-image

[6] These forces fought against the Russian Empire as a specific unit within the Austro-Hungarian Army during WWI and for the control of Galicia against Poland as the armed forces of the ephemeral West Ukrainian People’s Republic (ZUNR; 1918-19), respectively.

[7] Around the same place also stands a bleak column commemorating the struggle of the Ukrainian National Army* (УНА), a Nazi-sponsored military group founded in Weimar, Germany, amid the collapse of the Third Reich in early 1945. It included the infamous 14 th Waffen-SS division ‘Halychyna’ (Галичина, ‘Galician’ in Ukrainian). Many veterans of those units are buried in Lychakiv because of post-1991 efforts from nationalist Ukrainian organisations/movements to erect monuments in their memory in Galicia. Halychyna veteran Yurii Ferentsevych – who went into exile in Europe and North America after USSR’s victory in WWII and spent his life trying to safeguard *UNA’s legacy, first from abroad through emigrant veterans’ collectives and then back in Ukraine after the fall of Communism – is one of the most important initiators of such projects. The cemetery’s website modestly describes the sector as a burial place for people who “gave their lives to the heroic struggle for the freedom of the native people and the independence of Ukraine” . For further information, see lviv-lychakiv.com.ua or web.archive.org/web/20141006091640/http://www.plast.org.ua/news?newsid=5703

[8] Assma Maad, “Le mythe Bandera et la réalité d’un collaborateur des nazis” [ Bandera’s Myth and the Reality of a Nazi Collaborator ] Le Monde, January 8, 2023. www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2023/01/08/guerre-en-ukraine-le-mythe-bandera-et-la-realite-d-un-collaborateur-des-nazis_6157084_4355770.html

[9] John-Paul Himka, “The Lviv Pogrom of 1941: the Germans, Ukrainian Nationalists, and the Carnival Crowd” Canadian Slavonic Papers, 2011. dx.doi.org/10.1080/00085006.2011.11092673

[10] Ibid.: Those were mostly opportunistic moves made to arouse the sympathy of the Nazis in the naive hope that they would allow the foundation of an independent Ukrainian state in a hypothetical German-dominated Europe. However, as the OUN-led self-proclaimed ‘Ukrainian national government ’ in Lviv was instantly toppled and Bandera arrested by German occupation authorities, the OUN-UPA partisans turned their back on Berlin and fought both Nazi Germany and USSR until the end of the war. Nonetheless, they simultaneously continued to apply their antisemitic agenda and slaughtered Jews – even without Nazi backing – in Galicia and Volhynia.

[11] Maad, “Le mythe Bandera et la réalité d’un collaborateur des nazis”

[12] Ibid. For further information, read for instance about radical Ukrainian historian Volodymyr Viatrovych.

[13] Nikolay Koposov, “Les lois mémorielles en Russie et en Ukraine : une histoire croisée” [ Memory Laws in Russia and Ukraine: An Entangled History ] Écrire l’histoire n°16 , 251-256, 2016.

[14] Thomas d’Istria, “Stepan Bandera, the Ukrainian anti-hero glorified following the Russian invasion” Le Monde, January 12, 2023. www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2023/01/12/stepan-bandera-the-ukrainian-anti-hero-glorified-following-the-russian-invasion_6011401_4.html

[15] Lily Hyde, “Ukraine to Rewrite Soviet History with Controversial ‘Decommunisation’ Laws” The Guardian, April 20, 2015. www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/20/ukraine-decommunisation-law-soviet

[16] Ibid. : “The [decommunization] laws […] provide public recognition to anyone who fought for Ukrainian independence in the 20 th century.”

[17] Istria, “Stepan Bandera, the Ukrainian anti-hero glorified following the Russian invasion” ; see also “The Tenth National Survey: Ideological Markers of the War” Rating, April 27, 2022. ratinggroup.ua/en/research/ukraine/desyatyy_obschenacionalnyy_opros_ideologicheskie_markery_voyny_27_aprelya_2022.html

[18] Ibid. See also the conclusion of Andreas Umland, “Ukraine’s Far Right Today: Continuing Electoral Impotence and Growing Uncivil Society” Swedish Institute of International Affairs, March 2020. https://www.ui.se/globalassets/ui.se-eng/publications/ui-publications/2020/ui-brief-no.-3-2020.pdf

[19] Maad, “Le mythe Bandera et la réalité d’un collaborateur des nazis”

[20] The 14th Waffen-SS division ‘Halychyna’ also participated in some of these operations, particularly in the first half of 1944. Against the backdrop of the rapid Red Army’s advance on the Eastern front (Lviv fell in late July 1944), UPA partisans temporarily realigned with Nazi Germany to unite the struggle against their common enemy, hence the collaboration between SS units and Ukrainian nationalists.

[21] Timothy Snyder, “Genocide, Ethnic Cleansing, and Deportation: How Volhynia Became West Ukraine, 1939-46” Kennan Institute, January 30, 2002.

[22] See for example the 2016 Sejm’s resolution establishing a Polish “National Day of Remembrance for the Victimes of Genocide committed by Ukrainian nationalists against citizens of the Second Polish Republic” sejm.gov.pl/Sejm8.nsf/komunikat.xsp?documentId=2D76E3019FA691C3C1257FF800303676

[23] Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe, “The ‘Ukrainian National Revolution’ of 1941: Discourse and Practice of a Fascist Movement” Kritika Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, 84, December 2011. “[…] the OUN had two main types of enemies. The first were the ‘occupiers’, […] Poles and Soviets. The second group of enemies were the Jews, the largest stateless minority in Ukraine, who, according to the stereotype of ‘Judeo-Bolshevism’, were often associated with the Soviets.” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371397183_The_Ukrainian_National_Revolution_of_1941_Discourse_and_Practice_of_a_Fascist_Movement.

[24] Himka, “The Lviv Pogrom of 1941: the Germans, Ukrainian Nationalists, and the Carnival Crowd” , 234.

[25] Andrii Portnov, “Clash of victimhoods: the Volhynia Massacre in Polish and Ukrainian memory” openDemocracy, November 16, 2016. http://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/clash-of-victimhood-1943-volhynian-massacre-in-polish-and-ukrainian-culture/ “The ‘anti-Polish operation’ of the UPA was […] additionally inspired by the anti-Polish sentiments and experience of discriminatory politics of the interwar Polish state where people of Ukrainian origin had reasons to feel themselves ‘second-class citizens’.”

[26] Daniel Tilles, “‘We understand your pain’ over WWII massacre, Ukrainian leader tells Polish parliament” Notes from Poland, May 25, 2023. notesfrompoland.com/2023/05/25/we-understand-your-pain-over-wwii-massacre-ukrainian-leader-tells-polish-parliament/ “A common narrative in Ukraine has been that the Volhynia massacres must be contextualised by understanding previous Polish treatment of Ukrainians, for example repressive actions taken against them in the interwar Polish republic.”

[27] President Zelensky (2019-present) ignored demands from the Polish foreign ministry for a state apology in 2023 (see www.euronews.com/2023/07/07/polish-demand-for-recognition-of-wwii-massacres-sparks-row-with-ukraine) while President Poroshenko (2014-19) hardly conceded that Ukrainian and Polish people should “forgive each other” in 2014, (see euromaidanpress.com/2014/12/17/poles-and-ukrainians-must-forgive-each-other-poroshenko/) thus implicitly promoting the idea of a Polish-Ukrainian collective/symmetrical guilt regarding ethnic clashes in the 20th century. In 2016, after the Sejm passed a resolution on the remembrance of the massacres (see note n°23), he posted on Facebook that he “ [regretted this] decision” (www.facebook.com/petroporoshenko/posts/815996781868049)

[28] Stepien Stanislaw, “Les relations polono-ukrainiennes depuis la Seconde Guerre mondiale” [ Polish-Ukrainian Relations since the Second World War ] Matériaux pour l’histoire de notre temps, n°61-62 , 33-34, 2001. www.persee.fr/doc/mat_0769-3206_2001_num_61_1_403253

[29] The dominance of Catholic Polish noble landlords over Orthodox Ukrainian peasants eventually fostered deep-seated tensions that periodically flared into violence. The most prominent instance was the Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648 which freed the territory that would then become the first modern Ukrainian state from Polish control, while simultaneously bringing it under the influence of Russian tsars through the Treaty of Pereiaslav (1654). In Ukraine, this revolt is sometimes alluded to as the “National Liberation War” – a telling indication of the steady perception of Polish rule as oppressive.

[30] Stepien Stanislaw, “Les relations polono-ukrainiennes depuis la Seconde Guerre mondiale” , 33.

[31] One of the two brief post-WWI independent Ukrainian states, which was dismantled after the Bolshevik victory in the Ukrainian-Soviet War (1917-21).

[32] Stepien Stanislaw, “Les relations polono-ukrainiennes depuis la Seconde Guerre mondiale” , 34.

[33] “Ukraine: Poland’s President Arrives for Talks” RFE/RL, May 9, 1997. www.rferl.org/a/1084998.html

[34] See web.archive.org/web/20070928014907/http://www.nrcu.gov.ua/index.php?id=148&listid=15458 “The [Lviv City Rada’s] deputies set June 24th [2005] as the date to inaugurate the cemetery, taking into account the need to conclusively reconcile Ukrainian and Polish war veterans and Poland’s support for the orange revolution in Ukraine.”

[35] Gabriele Woidelko, “The Polish-Ukrainian Battle for the Past” Carnegie Endowment, December 15, 2017. carnegieendowment.org/europe/strategic-europe/2017/12/the-polish-ukrainian-battle-for-the-past “This decision forbids the exhumation of Poles who were victims of anti-Polish Ukrainian war crimes […]. Ukraine took this decision in response to the destruction of a monument to soldiers of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army […] in the Polish village of Hruszowice in April 2017.”

[36] “Poroshenko Lays Flowers at Monument to Victims of Volyn Tragedy” Ukrainska Pravda, July 8, 2016. www.pravda.com.ua/eng/news/2016/07/8/7114197/

[37] “Zelensky, Duda remember WWII Volhynia massacre victims” DW, September 7, 2023. www.dw.com/en/zelenskyy-duda-remember-wwii-volhynia-massacre-victims/a-66168573

[38] Una Hajdari, “Polish demand for recognition of WWII massacres sparks row with Ukraine” Euronews, July 7, 2023. www.euronews.com/2023/07/07/polish-demand-for-recognition-of-wwii-massacres-sparks-row-with-ukraine

[39] “Poland marks first national memorial day for Poles killed by Ukrainians in Volhynia” TVP World, July 11, 2025. tvpworld.com/87785928/poland-marks-first-national-memorial-day-for-poles-killed-by-ukrainians-in-volhynia “Kosiniak-Kamysz added that he ‘is not of those who could be described as trying to stoke some kind of discord between Poland and Ukraine,’ referring to conservative and far-right politicians who tie the country’s support for Kyiv in its war with Russia to issues around historical justice.”

[40] Jennifer Rankin, “Poland hails breakthrough with Ukraine over second world war Volhynia atrocity” The Guardian, January 16, 2025. www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jan/16/poland-hails-breakthrough-with-ukraine-over-second-world-war-volhynia-atrocity

[41] A widespread Ukrainian argument to downplay the ‘Volyn tragedy’ invokes the deaths of around 10,000 Ukrainians killed by Poles in acts of self-defense or retaliation for UPA-led violences in the 1940s.

[42] “Poland marks first national memorial day for Poles killed by Ukrainians in Volhynia” TVP World

[43] Veronika Melkozerova, “Poland and Ukraine’s bloody past overshadows their anti-Russia alliance” Politico, October 7, 2024. www.politico.eu/article/poland-and-ukraines-bloody-past-overshadows-their-anti-russia-alliance/

[Cover image] “Lychakiv Cemetery”, C.Guillot, 2025.

Leave a reply to John Wasiewicz Cancel reply